10 Pregnancy and Heat Stress

Thermal Physiology of the mother and fetus

Overview

Pregnancy increases metabolic demand, blood volume, and hormonal load, all of which alter the way the body manages heat. At the same time, the fetus contributes its own metabolic heat but cannot dissipate it independently. Together, these factors create a unique thermoregulatory challenge that becomes especially important in hot climates.

Maternal-Fetal Heat Exchange

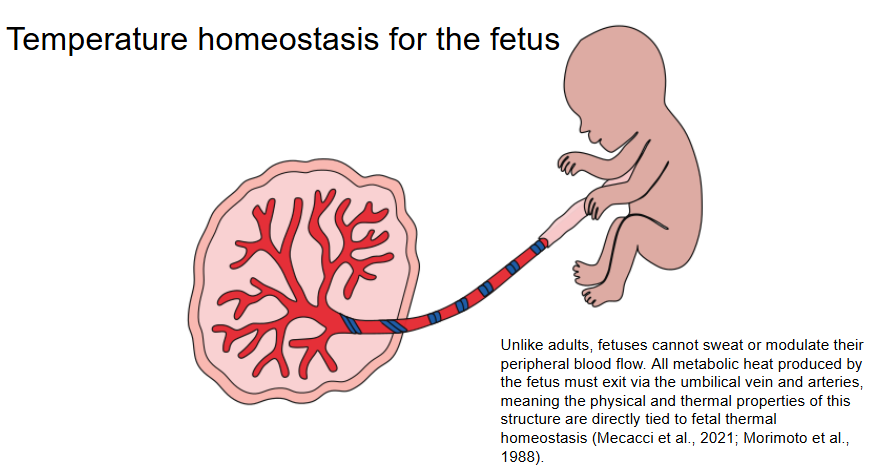

The fetus has no direct contact with the external environment and relies entirely on maternal systems to remove its heat. Fetal core temperature typically runs 0.3 to 1.0°C higher than the mother’s, creating a constant thermal gradient that drives heat transfer from fetus to mother.

Two primary pathways transfer fetal heat:

-

Convective route: Blood flow from the fetus through the umbilical arteries and back through the umbilical vein (~85% of heat loss)

-

Conductive route: Passive diffusion of heat through fetal skin, amniotic fluid, uterine wall, and maternal tissues (~15% of heat loss)

“Maternal temperature consistently underestimates fetal core temperature by up to 1°C. A maternal fever of 39°C may reflect a fetal core temperature exceeding 40°C” (Goetzl, 2023; Steer, 2023).

Placental Thermodynamics

The placenta is the key interface for thermal exchange. It contains:

-

~14 m² of surface area

-

At least 50 km of capillaries

-

A maternal-fetal barrier only a few microns thick

Its efficiency depends on:

-

Blood flow velocity and volume through the umbilical vessels

-

Placental vascular anatomy, including villous branching

-

Maternal skin temperature and vasodilation, which influence downstream heat dissipation

However, the human placenta is less thermally efficient than that of many mammals, due to its deep implantation and limited convective surface area (Schroder & Power, 1997).

Cardiovascular and Endocrine Adaptations

During pregnancy:

-

Cardiac output increases by 30 to 50%

-

Blood volume increases by up to 45%

-

Resting heart rate increases by 10 to 20 beats per minute

These changes help maintain fetal perfusion and support peripheral heat dissipation through increased skin blood flow. However, this leaves less cardiovascular reserve for thermoregulation under heat stress.

At the same time:

-

Progesterone remains high, elevating the maternal thermoregulatory set point

-

Estradiol promotes vasodilation, but cannot fully compensate for increased thermal load

-

Aldosterone and vasopressin levels increase to support fluid retention, which can be destabilised by sweating and dehydration

“Pregnancy is a state of chronically elevated thermogenesis. Thermal balance becomes fragile when ambient temperatures rise” (Kenney & Johnson, 1992; Samuels et al., 2022).

Immune System and Inflammation

Pregnancy requires a carefully regulated immune state. Heat stress may:

-

Trigger an inflammatory response, including cytokine release

-

Disrupt placental immune tolerance, increasing risk of preterm birth

-

Contribute to placental hypoperfusion and reduced nutrient transfer

Inflammatory markers such as TNF-α and IL-6 are elevated during heat exposure, and maternal endotoxemia may further increase fetal risk (Hall et al., 2001; Pearce et al., 2013).

Recap

-

The fetus depends entirely on maternal systems for thermal regulation

-

Heat is transferred primarily through blood circulation and secondarily via passive conduction

-

Pregnancy alters cardiovascular, hormonal, and immune systems in ways that increase vulnerability to heat

-

The placenta plays a critical but limited role in heat exchange, especially when external cooling is inadequate

References

-

Goetzl, L. (2023). Heat stress in pregnancy: A clinical perspective. Obstetrics & Gynecology.

-

Steer, P. (2023). Fetal core temperature and maternal hyperthermia. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology.

-

Samuels, L. et al. (2022). Heat and pregnancy: Evidence gaps and future directions. Environmental Health Perspectives, 130(2), 026001.

-

Hall, D. M., et al. (2001). Mechanisms of circulatory and intestinal barrier dysfunction during whole body hyperthermia. American Journal of Physiology–Heart and Circulatory Physiology, 280(2), H509–H521.

-

Pearce, S. C., et al. (2013). Heat stress reduces intestinal barrier integrity and alters immune responses in growing pigs. Journal of Animal Science, 91(3), 1090–1099.

-

Schroder, H., & Power, G. G. (1997). Heat exchange between fetus and mother. Seminars in Perinatology, 21(4), 276–287.

-

Kenney, W. L., & Johnson, J. M. (1992). Control of skin blood flow during exercise. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 24(3), 303–312.