4 History of Temperature Measurement

A Brief History of Measuring Heat

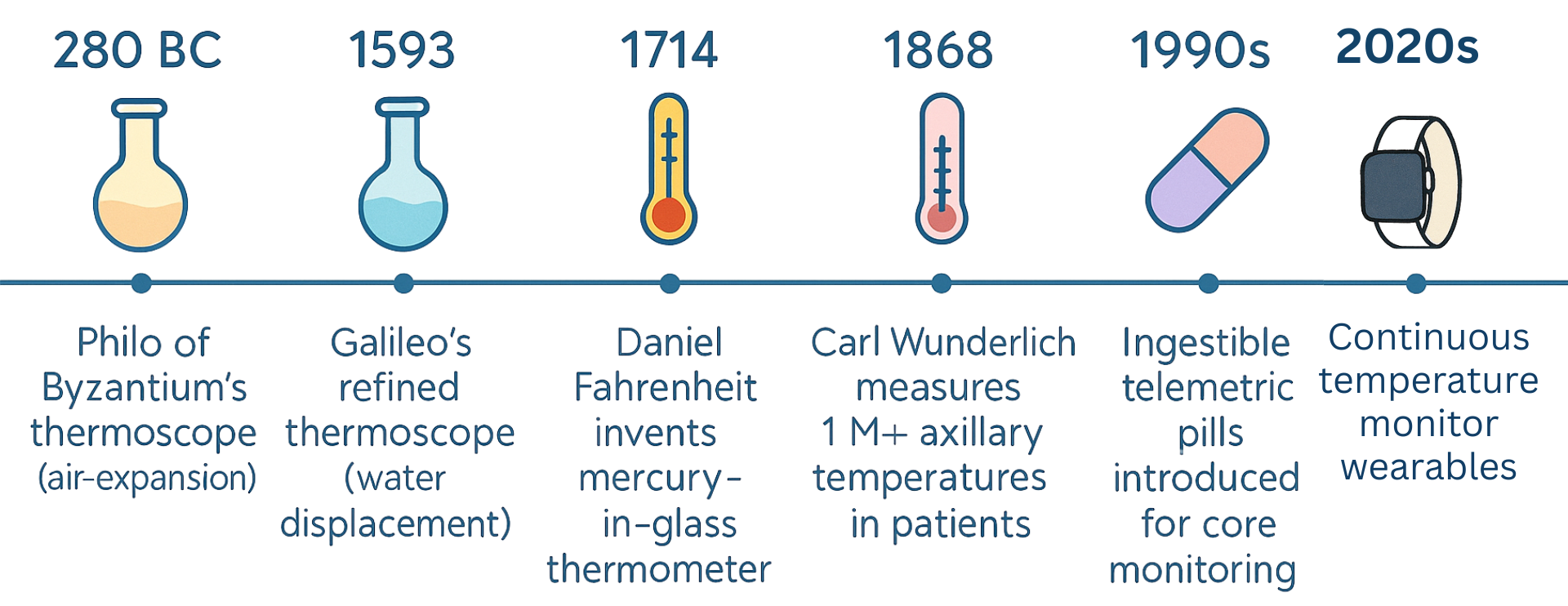

Efforts to quantify heat date back more than two millennia, but the modern understanding of “temperature” as a measurable and standardized concept is a relatively recent development. The history of thermal measurement reveals the gradual evolution of tools, scales, and scientific understanding that underpin today’s thermophysiology.

Early Concepts: Observing Heat Without Measuring It

The earliest recorded thermal instruments were not thermometers in the modern sense but thermoscopes—devices that demonstrated sensitivity to heat without quantifying it. Around 300 BCE, Philo of Byzantium constructed a rudimentary thermoscope consisting of a glass sphere connected to a tube submerged in water. When the device was exposed to sunlight, expanding air displaced the water in the tube, offering a visual indication of warming. This early innovation revealed a basic understanding of thermal expansion but lacked a numerical scale.

In the 1600s, Galileo Galilei developed a more refined version of the thermoscope. However, like Philo’s, it still lacked a fixed reference system or temperature units, making comparisons between instruments or over time unreliable.

These early inventions were based on qualitative responses to heat, not calibrated “degrees.” They were sensitive to air pressure and temperature changes but could not distinguish between the two.

Standardizing Temperature: From Scales to Science

A major leap occurred in the 18th century with the introduction of quantitative thermometry.

In 1714, Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit invented the mercury thermometer, which responded more consistently to thermal changes than alcohol- or water-based designs. He also introduced the Fahrenheit scale, setting the freezing point of water at 32°F and boiling at 212°F under standard atmospheric pressure. His work provided reproducible reference points for temperature measurement and paved the way for clinical and industrial applications.

Just a few decades later, Anders Celsius proposed a new centigrade system based on the boiling and freezing points of water. His original scale placed 0 at the boiling point and 100 at the freezing point, but it was soon reversed to form the Celsius scale used internationally today. These standardized temperature systems enabled accurate scientific comparison and laid the groundwork for understanding physiological responses to heat and cold.

Contemporary Technologies: Expanding Thermal Precision

Today, modern tools have vastly expanded the scope and precision of temperature measurement. These include:

-

Ingestible telemetry sensors that allow for accurate, real-time core temperature monitoring in athletes, pregnant individuals, and field research subjects

-

Skin-attached thermistors and thermocouples used for high-resolution skin temperature monitoring in both laboratory and outdoor environments

-

Infrared thermography, which provides non-contact mapping of skin surface temperature for research and clinical screening

These technologies are not only advancing scientific understanding of thermal physiology but also providing critical insights into how individuals respond to heat under variable environmental conditions.

Fertility and Temperature: From Pencil Drawn Charts to AI Wearables

The two-century journey, from glass tubes to calibrated scales and now continuous core temperature monitors, set the stage for today’s thermal innovations, where temperature monitoring not only diagnoses fevers or heat illness but also reveals accurate insights into women’s reproductive health.

In 1905, Dutch gynecologist Theodoor van de Velde first correlated a small rise in basal body temperature (BBT) with ovulation, noting that post-ovulatory temperatures were consistently 0.2–0.5 °C higher than follicular values (van de Velde, 1905). In the 1920s, Kyusaku Ogino and Hermann Knaus independently showed that ovulation occurs about fourteen days before the next menstrual period. Building on this, in the 1930s German priest Wilhelm Hillebrand formalized the “temperature method,” teaching couples to chart daily oral BBT readings to identify infertile and fertile phases of the menstrual cycle. While manual BBT charting revolutionized natural family planning, it depends on strict wake times, proper thermometer placement, and meticulous record-keeping – all of which introduce risk of error and user burden.

Today, femtech devices automate and refine these century-old principles by combining continuous thermal sensing with intelligent algorithms. Key advancements include:

- Overnight passive monitoring without rigid morning routines

- High-resolution sampling (many readings per night) with noise filtering

- Multi-sensor fusion, integrating temperature with heart-rate and perfusion data

- AI-driven fertile-window prediction and early-pregnancy detection

- Clinical-grade accuracy, benchmarked against LH tests, ultrasound, and core-body telemetry

- Privacy-forward designs that anonymize or localize data for user control

One landmark study in animal research showed that continuous core temperature monitoring could detect pregnancy in mice within 14 hours of mating (Smarr et al., 2016). Amazingly, Azure Grant (from Berkeley) showed in 2022 the potential for this in humans. Using the Oura ring in women, Grant and Smarr showed nightly peaks in distal-body temperature first rise to a distinct level at a median of 5.5 ± 3.5 days after conception. This happens about nine days earlier than most home pregnancy tests turn positive (around 14.5 ± 4.2 days after conception). This suggests that passive temperature monitoring could enable much earlier pregnancy detection.

Below, click each hotspot to explore today’s leading femtech temperature sensors.

Looking Ahead

The future of temperature measurement in health and environmental science is likely to be defined by continuous, wearable, and multi-sensor systems. These tools offer new opportunities to monitor reproductive status, heat vulnerability, and thermoregulatory adaptation in real-time. In an era of intensifying climate stress, particularly for pregnant individuals and those in thermally challenging environments, accurate and scalable temperature monitoring will be increasingly important.

References

Camuffo, D. (2021). Galileo’s revolution and the infancy of meteorology in Padua, Florence and Bologna. Méditerranée, 127, 25–39. https://doi.org/10.4000/mediterranee.12565

Chang, H. (2004). Inventing temperature: Measurement and scientific progress. Oxford University Press.

Grant, A. D., & Smarr, B. L. (2022). Feasibility of continuous distal body temperature for passive, early pregnancy detection. PLOS Digital Health, 1(5), e0000034. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pdig.0000034

Science Museum Group. (n.d.). Reconstruction of Philo’s thermoscope [Museum artifact]. Science Museum Group Collection. Retrieved [insert date], from https://collection.sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk/objects/co8548354

Smarr, B. L., Zucker, I., & Kriegsfeld, L. J. (2016). Detection of successful and unsuccessful pregnancies in mice within hours of pairing through frequency analysis of high temporal resolution core body temperature data. PLOS ONE, 11(7), e0160127. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160127

van de Velde, T. H. (1905). Ueber den Zusammenhang zwischen Ovarialfunction, Wellenbewegung und Menstrualblutung: Und ueber die Entstehung des sogenannten Mittelschmerzes. Bohn.

Media Attributions

- 2020s