3 Measuring and Quantifying Heat

How Do We Know When It’s Too Hot for Health?

Why Measurement Matters

Before we can understand how heat impacts the body, especially during menstruation, pregnancy, or fetal development, we need to measure it accurately. But temperature alone isn’t enough.

What matters more is how the body experiences heat—a complex mix of:

-

Air temperature

-

Humidity

-

Wind speed

-

Solar radiation

-

Clothing and activity level

Accurate measurement is important because individuals may face significant health risks even when ambient temperatures appear moderate. The body’s capacity to dissipate heat can vary considerably depending on context, such as hydration status, acclimatisation, or gestational stage.

Heat Stress and Heat Strain: A Conceptual Framework

In thermal physiology, it is helpful to distinguish between heat stress and heat strain. Heat stress refers to the combined environmental and metabolic load that promotes heat gain. This includes external heat sources, internal metabolic production, and barriers to heat dissipation. Heat strain, by contrast, describes the body’s physiological response to that load. It includes changes such as rising core temperature, elevated heart rate, dehydration, and thermal discomfort (Sawka et al., 2011).

This distinction is important in research and clinical settings. Two individuals exposed to the same temperature may experience very different levels of strain, depending on their fitness, pregnancy status, hydration, or hormonal profile.

Measuring Environmental Heat Exposure

Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT)

WBGT is widely used in occupational, athletic, and military settings and integrates three variables: dry bulb temperature (standard air temperature), wet bulb temperature (which reflects humidity), and black globe temperature (which accounts for radiant heat). This composite index is more predictive of heat strain than air temperature alone.

Authorities such as the International Olympic Committee, the U.S. military, and many occupational safety agencies recommend the use of WBGT to determine heat exposure thresholds. Risk increases significantly at WBGT values above 28°C for unacclimatised individuals, and above 32°C, heat illness becomes likely without active cooling strategies.

Heat Index and Humidex

The Heat Index and Humidex are simpler indices that combine temperature and relative humidity to describe perceived heat. These are commonly used in weather forecasts. For example, an ambient temperature of 33°C with high humidity may feel like 41°C. However, these indices do not account for wind, radiant heat, or activity level, and are therefore limited in precision when applied in clinical or research settings (Gosling et al., 2021).

Temperature-Humidity Index (THI)

THI is commonly used in studies of reproductive physiology in livestock. It has been linked to changes in conception rates and fetal development, particularly in dairy cattle, and serves as a useful model for understanding heat effects on reproductive health. Although developed for agricultural purposes, THI has informed hypotheses in human heat stress studies.

Comprehensive Climate Index (CCI)

The CCI includes a broader range of variables, such as solar radiation, wind speed, and precipitation. It is used in some public health and climate change research but has not yet been widely adopted in clinical or occupational practice.

Measuring Internal Thermal Load

Core Body Temperature

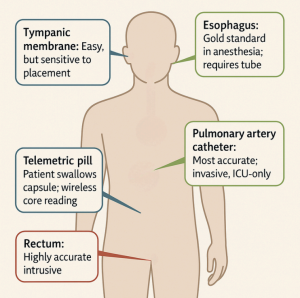

Core temperature is the most reliable indicator of physiological heat strain. It can be measured in several ways:

-

Rectal temperature is considered the gold standard in controlled research.

-

Esophageal temperature is also accurate but invasive and less commonly used.

-

Tympanic and oral methods are more convenient but tend to underestimate core temperature, especially during physical activity or heat exposure.

-

Ingestible temperature sensors (or telemetry pills) provide a practical and accurate method in field studies, including those involving pregnancy (Smallcombe et al., 2021).

Skin Temperature and the Core-to-Skin Gradient

Skin temperature reflects the body’s efforts to transfer heat to the environment. It rises during vasodilation, when warm blood is directed toward the skin surface, and falls during vasoconstriction, when the body seeks to conserve heat. While skin temperature varies across the body, it is generally higher on the trunk and lower at the extremities.

The difference between core and skin temperature—the core-to-skin gradient—is a valuable measure of heat dissipation efficiency. A narrowing gradient may signal impaired heat loss capacity, which can be an early sign of heat strain, particularly in the third trimester of pregnancy when baseline vasodilation is already high (Dervis et al., 2021).

Skin temperature is typically measured using thermistors or thermocouples placed at standardized locations such as the chest, upper arm, or thigh. Infrared thermography and wearable sensors are also used in research and clinical monitoring.

Physiological Indicators of Heat Strain

In addition to temperature, a number of physiological markers help identify when heat strain is occurring. These include:

-

Elevated heart rate

-

Increased sweat rate

-

Changes in hydration status (often assessed via urine osmolality or body mass)

-

Subjective discomfort or thermal fatigue

When used together with environmental indices and temperature readings, these measures help to characterise both acute and cumulative heat exposure risks.

Relevance to Pregnancy and Reproductive Health

The physiological stress of heat is not evenly distributed across populations. Pregnant individuals, for example, are more vulnerable to heat-related complications. Research increasingly suggests that ambient temperature alone is insufficient to predict clinical outcomes. Instead, meaningful assessment must consider exposure duration, humidity, gestational timing, and the capacity for behavioural or physiological adaptation.

Certain periods of gestation, such as implantation or the final trimester, appear to be more susceptible to heat-related disruptions. For instance, elevated ambient temperatures have been associated with preterm birth and reduced birth weight, although the precise mechanisms remain under investigation (Chersich et al., 2020; Dervis et al., 2021).

In one study, Healy et al. (2023) demonstrated that a 1°C increase in the standard deviation of daily temperature was associated with a 1.5% increase in mortality among older adults during warm seasons. Similar dose-response patterns may apply to maternal health, although further research is needed to establish thresholds for clinical intervention.

Summary

Effective heat measurement is central to understanding, predicting, and mitigating the effects of environmental heat on health. Simple temperature readings cannot capture the complexity of human heat stress. Tools like WBGT offer practical ways to assess external load, while core and skin temperature measurements provide insight into the body’s physiological response.

When applied to pregnancy, these methods reveal that individual vulnerability depends on a combination of physiological state, environmental load, and adaptive capacity. Future research should continue to refine our ability to measure and respond to heat exposure in ways that are sensitive to reproductive and life-stage differences.

References

Benkeser, M., Sander, L. D., Sarfo, A., et al. (2023). Comparing heat stress and heat strain across multiple occupational settings using physiological monitoring. Environmental Health Perspectives, 131(2), 27001. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP11426

Chersich, M. F., Pham, M. D., Areal, A., et al. (2020). Associations between high temperatures in pregnancy and risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and stillbirths: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ, 371, m3811. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3811

Dervis, S., Casasola, W., & Jay, O. (2021). Heat loss responses at rest and during exercise in pregnancy: A scoping review. Journal of Thermal Biology, 99, 103011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2021.103011

Gosling, S. N., Bryce, E., Lowe, R., & Bunker, A. (2021). A climate perspective on human thermal comfort indices. Nature Climate Change, 11(7), 574–579. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-021-01058-1

Healy, J. D., Zivin, J. G., & Neidell, M. (2023). Ambient temperature variability and mortality: Evidence from 20 years of data. The Lancet Planetary Health, 7(2), e122–e129. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00315-2

Kenney, W. L., & Johnson, J. M. (1992). Control of skin blood flow during exercise. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 24(3), 303–312. https://doi.org/10.1249/00005768-199203000-00010

Parsons, K. (2014). Human Thermal Environments: The Effects of Hot, Moderate, and Cold Environments on Human Health, Comfort and Performance (3rd ed.). CRC Press.

Sawka, M. N., Leon, L. R., Montain, S. J., & Sonna, L. A. (2011). Integrated physiological mechanisms of exercise performance, adaptation, and maladaptation to heat stress. Comprehensive Physiology, 1(4), 1883–1928. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c100082

Smallcombe, J. W., Casasola, W., Edwards, K. M., & Jay, O. (2021). Thermoregulation during pregnancy: A controlled trial investigating the risk of maternal hyperthermia during exercise in the heat. Sports Medicine, 51(12), 2655–2664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-021-01504-y

Media Attributions

- Screenshot 2025-06-09 004704