48 Electronic Signature

Rachael Samberg

Desired Result

As we discuss further in the Signature Block chapter, United States law does not impose many formalities for how a written agreement should be signed by the parties, and many forms of signature will suffice.[1] Electronic signatures are enforceable provided the parties intend to be bound by them. Parties can express this intent either by a pattern of conduct, or via explicit agreement. Given the risk that seemingly informal e-mail communications could constitute a binding agreement, it is advisable to include a provision confirming the parties’ intent to be bound by e-signatures and that the e-signatures are valid only as part of a formal, written agreement that supersedes all prior communications (for more on this, see the chapter on Entire Agreement (a.k.a. integration clauses.)

What it Means

Traditional manual signatures are often referred to as “wet” or “wet ink” signatures. As parties have increasingly engaged in business both globally and electronically, legislatures at a state and federal level have enacted legislation to promote interstate and international commerce by ensuring that, for certain types of transactions, e-signatures may be given the same force and effect as wet signatures. At the federal level there is the Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce Act (“E-SIGN”) of 2000 (15 U.S.C. §§ 7001 to 7031). At the state level, all states except for New York have adopted a version of the model Uniform Electronic Transactions Act (“UETA”); New York has its own equivalent. [2] E-SIGN and UETA uphold that an electronic signature satisfies the statute of frauds, which requires a “writing” and signature for contract authentication and enforceability. [3].

Under these statutes, e-signatures can be any electronic writing, sound, symbol, process that is “intentionally attached to or logically associated with the contract” and further intended to execute the agreement. [4]. You might be wondering why we are mentioning these seemingly non-standard means of acceptable e-signatures when, for your institutional license agreements, you fully intend to use a typical handwriting equivalent. It’s important to understand that many things can constitute an e-signature, including merely a typed name at the end of an e-mail—because you may inadvertently be agreeing and binding your institution to terms and conditions. [5]

Therefore, if you typically negotiate with vendors via e-mail, it is advisable to take extra precautions to limit the risk of having those e-mails constitute a binding agreement: Specifically, include an Integration clause [LINK] in the written agreement that supersedes any external or previous terms and conditions, and ensure your e-signatures clause in the agreement indicates that electronic signatures are binding only in the manner and to the extent signed below in the agreement (rather than as part of other communications).

Desired Language

CDL’s model language for this provision is basic:

Electronic Signatures: The parties agree that scanned and/or electronically signed versions of this originally executed Agreement are acceptable in lieu of printed signed copies and are to be given full force and effect under law.

You may wish to strengthen the clause by reducing the risk of external communications forming a binding agreement. For instance, you could add the following to the end of the above statement:

Consent to electronic signatures is provided solely for the purpose of executing this Agreement, and a party’s signature is binding only when placed next to their name in the signature page below.

Tricks & Traps

To reduce the risk that informal e-mail communications constitute electronically signed agreements, you could consider adding a header or footer to your e-mail correspondence with vendors, asserting that your e-mail does not constitute or create a binding contract or enforceable obligation, and that any agreement must be set forth separately in an integrated agreement signed by authorized representatives. Some courts have found this to be an effective disclaimer. [6].

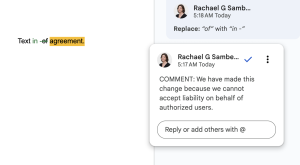

We also have a practical suggestion on how to conduct negotiations to minimize such risks. Engaging in protracted discussions via e-mail, rather than in the agreement itself, can create confusion, lead to misunderstanding of what was accepted or agreed upon, and poses greater risk of being considered a binding agreement. When we negotiate agreements, we do all of our modifications in redlined agreement documents. To explain our changes, we leave comments in the document itself, making them visible to the reviewing counsel or vendor by writing “COMMENT” in the box, like this:

When we transmit a newly-revised draft of the agreement back to the vendor, we briefly summarize the changes we made, but refer them specifically to the redlined agreement for specifics.

Importance and Risk

Electronic signatures can be vital to your licensing workflows. Using the above strategies will help ensure that only your definitive and integrated writing constitutes an agreement between the parties.

- 17A Am. Jur. 2d Contracts § 175. ↵

- In New York: Electronic Signatures and Records Act (ESRA). ↵

- UETA §§ 5(b) and 7(d). Note that E-SIGN and UETA do not apply to all types of agreements. For instance, wills are not included, and other UETA exemptions vary by state. 15 U.S.C. § 7003 and UETA § 3(b).) ↵

- UETA § 2(8) and 15 U.S.C. § 7006(5). ↵

- See, e.g., BrewFab, LLC v. 3 Delta, Inc., 2022 WL 7214223 at *5 (11th Cir. Oct. 13, 2022) (printed name in text message satisfied electronic signature under Florida law and was “reasonably associated” with overarching guaranty agreement); US Iron FLA v. GAM Garnett (USA) Corp., 2023 WL 2731714 at *9 (N.D. Fla. March 2, 2023) (standard course of conduct using e-mails and attaching their signature block to e-mail constituted authenticated agreement under Statute of Frauds, binding parties to revised purchase order terms); Crestwood Shops v. Hilkene, 197 S.W.3d 641 (Mo.App. W.D.,2006) (e-mail formed valid lease agreement). ↵

- See, e.g., Dhillon v. Zions First Nat’l Bank, 462 F. App’x 880 (11th Cir. 2012); McCoy v. Gamesa Tech. Corp., 2012 WL 983747, at *3 (N.D. Ill. Mar. 22, 2012) ↵