1 Copyright

David Bamman; Brandon Butler; Kyle K. Courtney; and Brianna L. Schofield

Copyright use case

To illustrate some of the copyright issues that arise for text data mining (“TDM”) research, we can consider a use case that raises a number of common issues in different applications in TDM. Let’s assume we have some collection of texts in varying copyright status, and we want to carry out some algorithmic transformation of those texts and publish the results. So envision this scenario: you’re a researcher who has a large collection of texts already digitized, and what you want to do is perform some natural language processing on those texts and visualize their results for the broader public.

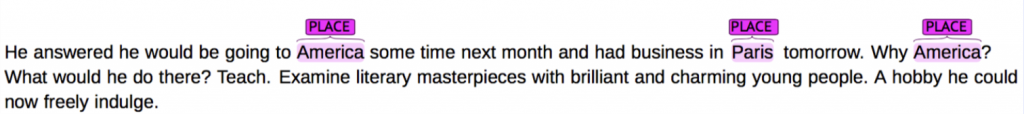

In particular, you have a large collection of fictional texts and what you want to do is extract all of the mentions of place names from each of these texts and plot those place names on a map. This is an aspect of text mining that’s known by a number of different terms, including toponym resolution and geolocation, but it starts from the fundamental problem of named entity recognition (“NER”)—of simply recognizing all of the names in the text that refer to places. So you extract those place names, georeference them to latitude/longitude coordinates on a map, and the visualization you want to present is effectively an organizing system for your fiction corpus: whenever a user clicks on a place in a map, you want to present to them a list of all the times when that place was mentioned in a book in your collection, including a snippet from the text where that place name was mentioned.

In the example above, a user has clicked on “Paris” and we can see that “Paris” shows up in works by Charles Dickens, Henry James, Zora Neale Hurston, Vladmir Nabokov, and Margaret Atwood. This involves a fundamental transformation of the data in several ways—not least of which is the fact that you are disambiguating place name mentions—and asserting, for example, that when Charles Dickens mentions “Paris” in Bleak House, he’s not talking about Paris, TX, he’s talking about Paris, France.

In this use case, the books you hold in your collection of fiction are relatively heterogeneous, and span over two hundred years—being published anywhere between 1800 and 2020. All of these books originate in print form (so, for example, they are not born digital as markdown files or Kindle editions); they’re print works that you’ve scanned and OCR’d (that is, an optical character recognition tool has been used so that all of text on a page image has been recognized). Your corpus also includes some unpublished manuscripts that are housed within your own library collections. The transformations that you are performing on this dataset is NER and toponym—where you extract all mentions of place names from text, and then ground those place names in specific coordinates on a map.

But your use case doesn’t just stop at running an NER system on your dataset and plotting those names on a map. You know that just about all of the existing NER systems out there are trained on data that’s not fiction, and you know you can do better if you train your own system on data that actually includes it. So what you want to do in your project is create training data in the domain you care about—fiction written between 1800 and 2020. This data is going to help you train better NER systems for recognizing places as they show up in literature. To achieve this, you take 1,000 novels from your dataset and annotate all of the place names that show up in a 500-word sample of each one, effectively creating a total labeled dataset that’s 500,000 words long. Your primary goal in creating this dataset is to make NER better for your visualization, but at the same time you recognize that this dataset really would be of tremendous value to the research community. It would allow computational researchers to train and evaluate models for NER on a domain that simply does not have much annotated data, and you would be helping the community be less focused on news while at the same time helping improve these tools for other researchers in the humanities who work with these texts. So in addition to publishing your interactive visualization of place names mentioned in fiction, you also want to publish your annotated dataset of 500,000 words for others to use. You value reproducibility as a scientific goal and want to have that dataset out there in the world. You can see below what one of these annotations would look like—you want to publish a 500-word snippet of, for example, Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire—along with your annotations for which words are places within it, for all of the 1,000 novels in your annotated dataset.

So those are the two main aspects of this use case we’re working with: (1) creating a visualization plotting place names extracted from fiction on a map using algorithmic transformations of NER and toponym resolution, and (2) publishing a new annotated dataset of place names mentioned in these works. Let’s keep this use case in mind through this chapter, and we’ll return to it at the end.

Copyright basics

Copyright law is part of a legal system that covers both creation and use. Here we will cover the copyright basics: what copyright is, what copyright protects, and how long copyright protection lasts. Additionally, copyright law is filled with exceptions and exemptions that strike a balance between the exclusive rights granted to creators and the rights of many users, including TDM researchers. It is critical that TDM researchers understand both the rights and the exceptions, with an emphasis on fair use, which in the TDM context is one of the most important rights that provides a legal justification for using the material that drives a TDM project. However, before the exceptions, which are covered in a later section, let us start with the copyright basics.

In 1710 the English parliament passed the Statute of Anne. This new law gave authors, for the first time in history, an economic incentive to create new works: Authors had control of their own works, and the copies made, via a limited economic monopoly—not unlike our modern understanding of copyright. This captured the first balance between authors’ rights and the public benefit of copyright, when works drop into the public domain. This temporary economic right was enough incentive for authors to continue to create new works. And, of course, when the rights expired (after 14 years) the work would drop into the public domain, and anyone could use the work thereafter without permission. This encapsulated the cycle of copyright: creation, control, and expiration, with the hope that further works could be created using what dropped into the public domain. And in fact, the Act starts with the language, “An Act for the Encouragement of Learning.”

This concept moved into the U.S. system in our Constitution. Certainly, the members of the United States Constitutional Convention were aware of the ideas of control and censorship as the U.S. emerged from English rule. In 1790, pursuant to their Constitutional authority under Constitutional Clause: Article 1, section 8, clause 8: “To promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries,” the Congress passed, and George Washington signed, the first copyright law in the United States. It was also titled “An Act for the Encouragement of Learning” and featured the same balance that the English had revolutionized with the Statute of Anne: an incentive of a limited economic monopoly granted to authors over their works, followed by the expiration of those rights when the work then would drop into the public domain.

The current copyright law on the books is based on that initial 1790 law, but now it is in the U.S. code as the Copyright Act of 1976. It protects original works of authorship that are fixed in any tangible medium of expression.

But what is an “original work of authorship”? An original work must embody some “minimum amount of creativity.” Courts have held that almost any spark beyond the trivial will constitute sufficient originality. On the other hand, the Supreme Court ruled in 1991 that a garden variety alphabetical, white pages telephone book lacks the minimum creativity necessary for copyright protection. This is called the Feist case. The U.S. Supreme Court held in Feist Publications v. Rural Telephone Service that copying of a white pages book was not infringement because there was no existing copyright. However, although facts themselves are not copyrightable, the way the items are categorized and arranged may be original enough to satisfy the originality requirement.

Ultimately, this creativity threshold is also touched upon in another part of the Copyright Act, section 102(b), which states that copyright’s threshold for originality does extend to “any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery.” From this we gather an important point for authors: facts are not copyrightable.

But, beyond creativity, what is copyright, really? Is it a “bundle of rights”? A limited economic monopoly for authors? Or, in the Constitutional narrative, is it a system “to promote the progress of science and the useful arts”?

Well for copyright to work, it has to be all three. The cycle of creation, dissemination, and expiration of rights into the public domain is a critical component of copyright law. Without this balance, the system loses its value, or prevents the public from receiving the benefit of the bargain. The bargain is made by granting limited economic monopolies to incentivise creation, and then, after expiration of the monopoly, the benefit is effectively giving that material to the public for unimpeded use, thus inspiring more works to be harnessed and used.

When a work is creative and fixed, creators automatically get this exclusive bundle of rights. These are the rights: to reproduce the work copies; to prepare derivative works; to distribute copies; to perform the copyrighted work publicly; and to display the copyrighted work publicly.

In 1790, when George Washington signed our country’s first copyright law into existence, copyright protection was for books, maps, and charts. However, under the Copyright Act of 1976, the subject matter of copyright has been extended into these eight extensive categories: (1) literary works; (2) musical works, including any accompanying words; (3) dramatic works, including any accompanying music; (4) pantomimes and choreographic works; (5) pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works; (6) motion pictures and other audiovisual works; (7) sound recordings; and (8) architectural works. As Congress indicated in the creation of these categories, there is a great deal of material that has the potential to be protected by copyright.

Occasionally we learn about copyright by understanding what’s not copyrightable. For example, there are other parts of intellectual property law that are not under the umbrella of copyright. Slogans and logos, for example, are part of trademark law. Trademark law is generally all about what the mind of the consumers think as the source of the material when they see a logo. Patent law covers new and useful ideas such as processes, methods, and systems that are separate from copyright. Secret formulas and recipes that are not disclosed to the public are generally considered trade secrets. They derive economic value by not being disclosed to the public. And then, of course, there’s raw data. As we know from Feist, our white pages telephone book case, you can’t copyright a fact. Applying that holding here, raw data then, viewed as a set of facts, is uncopyrightable.

In order to know understand copyright, you need to know these six things: that creators get copyright if the work is original, creative, and fixed in a tangible medium of expression; that no registration is required to get copyright—the work is automatically granted protection under copyright if it’s creative and fixed; that the grant of rights to the author is represented by the exclusive bundle of rights in section 106; that there is a wide range of protected works; and they have a long term of protection. However, as we will cover, despite all of these rights there are numerous exceptions and limitations. The focus of our inquiry for TDM will be section 107 fair use.

However, before we move to the exceptions, we will cover a critical part of the copyright cycle: the public domain. When copyright was first passed by Congress in 1790, Congress set a term of protection for 14 years, with a potential of an additional 14 years if the creator renewed the copyright. In 1909, Congress doubled that timeline and copyright moved to a 28-year term of protection with a potential 28-year renewal. In 1976, in accordance with harmonizing international copyright law, as part of the Copyright Act of 1976, the term was set to life of the author plus 50 years. And in 1998, that term was expanded by Congress for an additional 20 years. And so, copyright today is measured by the life of the author plus 70 years. But what happens after expiration? Our next segment will cover that which is in the public domain.

The public domain

The previous section of this chapter covered what copyright is, what copyright protects, and how long copyright protection lasts. This section addresses the flip side of copyright: the public domain.

In copyright, the public domain is the commons of material that is not protected by copyright. Anyone is free to use, copy, share, and remix material that is in the public domain. The public domain includes works for which the copyright has expired, works for which copyright owners failed to comply with “formalities,” and things that are just not copyrightable at all. This section discusses each of these categories in turn.

A word of caution: Some people mistakenly think that the “public domain” means anything that is publicly available. This is wrong. The public domain has nothing to do with what is readily available for public consumption. This means that just because something is on the internet, it doesn’t put it in the public domain.

Remember that under today’s copyright laws, a work of creative, original expression simply needs to be “fixed in a tangible medium” to be eligible for copyright protection. If Philippa Photographer takes a photograph and puts it online on her blog, it doesn’t mean that she is also granting you permission to reuse it. The default is that Philippa’s photo is protected by copyright and not in the public domain.

Copyright expiration

One way content enters the public domain and becomes free of copyright protection is through copyright expiration.

Copyright protects works for a limited time. After that, copyright expires and works fall into the public domain and are free to use. Under United States copyright law, in 2021 (the year this book is being released) all works first published in the US in 1925 or earlier are now in the public domain due to copyright expiration. That said, unpublished works created before 1926 could still be protected by copyright. And under today’s copyright laws, works created by an individual author today won’t enter the public domain until 70 years after that author’s death.

When copyright does expire, the work is in the public domain and there are no copyright restrictions. For example, the book Alice in Wonderland is in the public domain, as are New York Times articles from the 1910s, because their term has expired. This means anyone may do anything they want with the works, including activities that were formerly the “exclusive right” of the copyright holder, like making copies and selling them.

Failure to comply with formalities

Another way a work may enter the public domain is through a failure to comply with formalities.

Copyright law used to require copyright owners to comply with certain requirements called “formalities” in order to secure copyright protection. These formalities included things like requiring the copyright owner to mark the work with a copyright notice and renew the initial term of copyright. These requirements existed in some form through March 1989. Because many authors failed to comply, many works from between 1926 and March 1989 may be in the public domain. But this analysis needs to be done on a case-by-case basis based on the facts surrounding a particular work. In some cases, a fair use analysis may be easier than making a conclusion about the copyright status of a work. (Fair use is discussed later in this chapter.)

If a work is in the public domain for failure to comply with formalities, as with copyright expiration, there are no copyright restrictions.

Uncopyrightable subject matter and other exclusions

In addition to copyright expiration and a failure to comply with formalities, copyright law also sets out things that are simply not protected by copyright, and those things are also in the public domain. This goes back to a point about the purpose of copyright: The public domain is important to the production of creativity; authors need these essential building blocks with which to work.

For example, facts are a category of things that are not copyrightable—even if those facts were difficult to collect. For instance, suppose that a historian spent several years reviewing field reports and compiling an exact, day-by-day chronology of military actions during the Vietnam War. Even though the historian expended significant time and resources to create this chronology, the facts themselves would be free for anyone to use. That said, the way that the facts are expressed—such as in an article or a book—is copyrightable.

Under United States copyright law, other types of works and subject matter do not qualify for copyright protection include: names, titles, and short phrases; typeface, fonts, and lettering; blank forms; and familiar symbols and designs. It is worth noting that other areas of intellectual property, such as patent or trademark law, could provide protection for categories that are not eligible for copyright protection.

The Copyright Act also provides that works created by the United States federal government are never eligible for copyright protection, though this rule does not apply to works created by U.S. state governments or foreign governments. And under the government edicts doctrine, judicial opinions, administrative rulings, legislative enactments, public ordinances, and similar official legal documents are not copyrightable for reasons of public policy.

Public domain and TDM projects

If a text data mining project involves only public domain materials (like federal government documents or newspaper articles published in the United States in the 1890s), there is no need to investigate whether accessing, using, and sharing of these public domain materials is allowable under an exception to copyright or whether you need permission from the copyright owner to use the work. This is because anyone can use public domain materials without infringing on copyrights, including activities that were formerly the “exclusive right” of the copyright holder like making copies of, sharing, and adapting the work.

Copyright, licensing, and permissions

You can learn about licenses in more detail in the Licensing chapter of this book, but copyright and licensing are so closely connected that we think it’s important to say a bit about them here, too.

A license grants permission, and may limit your rights, too

A license is a grant of authorization from a copyright holder to exercise one of their exclusive rights—in a research library context, typically the license is to copy or display protected works on your computer. Databases, journal literature, and other electronic content is often made available under a license either directly to the user or to an institution (typically a library) on behalf of its users. The license tells you which uses have been authorized, and authorization is often conditioned on the licensee doing certain things (most importantly, for commercial entities: paying a fee!).

A license may also include promises by the institution or the user not to engage in certain uses, or only to use licensed content under certain circumstances.

What this means for TDM researchers is that your institution may already have a license that defines what sorts of uses you can make of licensed content. You’ll need to read the license, or talk to someone who understands the license terms, to learn more about what uses are possible. You may also need to negotiate a new license to enable your use, especially if you require special kinds of access to a vendor’s content in order to conduct your research.

We talk a lot more about this in the chapter on licensing, but the key thing to understand, here, is that if your use is permitted by a license, then you don’t have to worry about copyright. If it is not clearly permitted, you will need to think about fair use and other alternatives. Fair use may permit uses that are not mentioned explicitly in a license, because a fair use does not require permission. If your use is forbidden by the license, then even if your use doesn’t violate copyright law, you or your institution could still face liability for breach of contract. The most likely negative consequence for violating a license is that you or your institution lose access to the resource, at least temporarily.

Creative Commons and other open licenses

Some works are available under open licenses that allow anyone to make specific uses of copyrighted works without the need to pay or seek additional permission from the owner. Creative Commons (“CC”) licenses are the most well-known open licenses. Creative Commons is a nonprofit organization that offers a simple, standard way to grant copyright permissions for creative works, and a suite of license options that lets authors impose some commonly-sought limitations on would-be users. Instead of the “all rights reserved” default, copyright owners can apply a CC license that allows others to use and share their works without seeking permission. It is important to pay attention to the specific terms of the license: almost all of the CC licenses require attribution, some can require you to “share alike” (i.e., to attach the same license to any work you create using the licensed work), and some restrict commercial uses or the creation of derivative works (like translations). For example, a work marked CC-BY-NC means that it is licensed for other people to use and share as long as the work is appropriately credited, but commercial uses are not allowed.

Creative Commons also offers a tool, CC0, that allows a copyright owner to waive all copyrights (and some related rights) in works. Because it is a complete waiver of rights, CC0 doesn’t require attribution.

CC licenses are especially common in the academic world, and research funders increasingly require their grantees to use them. But even non-academic works may be made available under CC licenses. For example, some museums distribute photographs of works in their collections under open licenses.

Bottom line: If works are made available under a public license, then (just like any other license) these works can be used in ways that comply with the terms of the license. If a TDM project involves works that are made available under a license, including a public license (like a CC license), these works can certainly be used in ways that comply with the terms of the license. If your use is beyond the terms of the license, or forbidden, things get more complicated. This issue will be discussed further in the chapter on licensing.

Fair use: A critical copyright exception

Imagine if all creators had to wait for a copyrighted work to be in the public domain before they used that work? Or if scholars always had to seek permission to use or quote, and that permission could be denied with no recourse? Happily, copyright law gives us the flexibility to allow some uses that are made during the copyright term without permission. One of the most famous of all the copyright limitations in the Copyright Act does just that: the fair use exception.

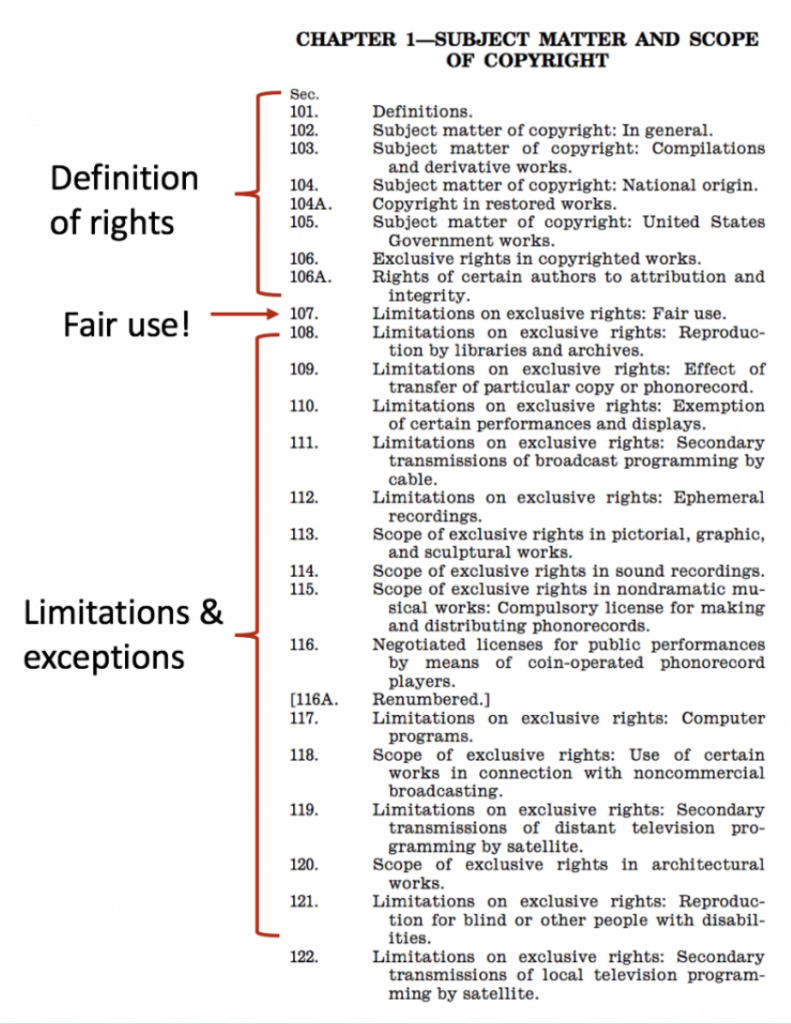

Under fair use, a person may use certain amounts of copyrighted material without permission from the copyright owner in some circumstances. The doctrine itself was rooted in both English and U.S. case law, but was eventually codified in section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act. Fair use, as you can see in the image below, sits in the middle of the organized balance in the Copyright Act; it is squeezed right between the exclusive rights and more specific exceptions.

Fair use is for everyone. And since TDM often involves copying large amounts of copyright material in order to mine the content, it is useful to the TDM researcher, because TDM involves access, coping, and processing works that may be in copyright.

Even if TDM researchers have authorized access to the materials, copying a substantial part of these works may infringe copyright in those works. And so might distribution after the copying and processing is over.

If a use is a fair use, it is not infringement. Again, imagine if you had to get permission to provide analysis, commentary, or criticism of someone’s copyrighted work. If there were no fair use, and copyright holders could forbid you from using the work without permission, this would vastly stifle free expression and new modes of scholarship, like TDM.

Fair use is a user’s right that allows individuals to exercise one or more of the exclusive bundle of rights of the copyright owner, without obtaining the permission from that copyright owner, and without the payment of any license fee.

To decide whether a use is fair, courts must consider at least four factors that are specifically mentioned in the Copyright Act.

17 U.S.C. §107

Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.

In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include—

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The first factor is the purpose and character of the use. Here courts ask whether the material has been transformed by adding new meaning or expression, or whether value was added by creating new information, meaning, or understanding. When a work is used for a different purpose than the original, the factor will likely weigh in favor of fair use. If it simply acts as a substitute for the original work, the less likely it is to be fair. Courts may also look at whether the use of the material was for commercial or noncommercial purposes under this factor, but this is rarely a determinative consideration.

The second factor looks at the nature of the copyrighted work. Here courts look at whether the copyrighted work that was used is creative or factual in nature (a song or a novel vs. technical article or news item). The more factual the work, the more likely this factor will weigh in favor of fair use. On the flip side, the more creative the copyrighted work, the more likely this factor is to weigh against fair use. Courts may also consider whether the copyrighted work is published or unpublished. If the work is unpublished, this factor is less likely to weigh in favor or fair use. Note that this factor has been slightly deemphasized by the courts over the last twenty years.

The third factor is the amount and substantiality of the portion taken. Under this factor, courts look at how much of the work was taken, both quantitatively and qualitatively. Quantitatively, courts look at how much of the original work was used (e.g., all the pages, the entire work of art). Qualitatively, some courts look at whether the “heart” of the work was taken (e.g., the essential bit of the work that is why people want to engage and acquire the work). The more that is taken, quantitatively and qualitatively, the less likely the use is to be fair. That said, copying a full work can absolutely be a fair use depending on the circumstances.

Finally, the fourth factor is the effect of the use on the potential market. The essential question courts ask here is whether this use will undermine the market, or the potential market, for the work that was copied. In assessing this factor, courts consider whether the use would hurt the market for the original work (for example, by displacing sales of the original). There’s a lot more nuance to this factor, but let’s move ahead to transformative fair use.

Transformative fair use

In 1841, the U.S. decided its first fair use case. And, as case law developed, so did new and different fair use theories. One of the more interesting developments in fair use litigation was the emergence of transformative fair use. Use of any copyrighted materials is substantially more likely to pass fair use muster if the use is transformative. A work is transformative if, in the words of the Supreme Court, it “adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning or message.” Transformative fair use is still a use without permission, but it is the legal engine which drives scholarship, research, and teaching.

The last two decades has seen a shift in courts analysis of the fair use test in creative endeavors like these. In transformative fair use, we see the courts collapsing the traditional “four fair use factors” to ask the following questions:

- Does the new use transform the material, by using it for a different purpose?

- Was the amount taken appropriate to the new, transformative purpose?

And, importantly, it helps to identify that this new transformative use has a different purpose than the original item’s purpose. For example, the original purpose of the fictional books in the Copyright Use Case was for entertainment. The new use should be for a different purpose—and arguably, the new purpose would be to add commentary or analysis that reveals a new meaning or message, altering the original works with new commentary, expression, meaning, or message.

Fair use law is well equipped to be adaptable to various scenarios. That’s the purpose of fair use: flexibility. Fair use is not mechanically applied or even weighed equally. Courts take into account all the facts and circumstances of a specific case to decide if use of copyrighted material is fair. And scholars, TDM researchers, librarians, lawyers, students, staff, and faculty can also use the fair use statute and legal decisions to evaluate their own fair use risk calculus for their own scenarios.

In the next section, we’ll look to see how fair use is applied specifically in the TDM mining context.

Fair use & TDM

As you’ve seen, fair use is a judge-made right that evolves as it is applied, case-by-case. Lawsuits about research and education are few and far between, so TDM researchers are unusually fortunate to have a long and deep line of cases that provides fairly clear support for the kinds of things they do with in-copyright material. Search engine operators like Google were sued early in their history, then related machine learning and computer analysis technologies were challenged, and finally massive digitization of research materials was challenged in the Google Books and HathiTrust cases, which we’ll explore in depth.

What’s key for TDM researchers to know is that courts have now blessed core TDM practices many times over. If anything is knowable in fair use law, we now know that these core TDM research methods are well-suited for fair use.

Key case: Authors Guild v. Google

Let’s take a look at how fair use applies to text data mining using a recent case, Authors Guild v. Google, as an example. This case arose when Google made digital copies of millions of books from partner research libraries, and made the resulting corpus searchable through its Google Books service. Google provided digital copies to the libraries who provided print books from their collections, and the libraries banded together to create the HathiTrust to manage the collective collection of those scans, together with other digital content.

Using Google Book Search, users could identify books that contained a desired word or phrase. Google’s search results showed limited snippets of the text (about an eighth of a page) so users could see their term in context and get a better sense of the result’s relevance to their interest. They also linked users to local libraries and online bookstores where copies of the work could be found. When the Authors Guild sued alleging infringement, Google argued that Book Search was a quintessential fair use. The influential Second Circuit court of appeals agreed. The Authors Guild sued HathiTrust and some of its members in a separate case, with the same result—fair use.

For TDM researchers, it is important to look at the three key uses that the court was evaluating in the Google Books case. Comparing your activities to the ones analyzed here will be extremely helpful as you figure out how fair use might apply to your research. The uses in the Google Books case were:

- Copying millions of complete in-copyright books to create a search index;

- Displaying “snippets” of in-copyright text as search results to users in the public; and

- Ngram graphs showing the frequency of words and phrases in the corpus over time.

These kinds of practices—compiling works into a machine-readable corpus and revealing relevant portions of the corpus to the public to substantiate or instantiate the results of machine analysis—are likely to recur in many, many TDM projects. Researchers will learn a great deal from a close reading of the court’s clear and detailed application of fair use to both practices.

First factor and transformative use

Recall that the first factor asks us to look at the purpose and the character of the use, and central to the analysis is whether a use is “transformative,” with transformative uses being much more likely to be fair use.

In Authors Guild v. Google, the Second Circuit held that three key activities by Google were all “highly transformative”:

- Copying of the entire text of books to create a searchable index;

- Display of snippets from books as part of the search process, to help users identify relevant search results; and

- Creating the ngram tool to show frequency of words and phrases in the corpus over time.

The court said that the purpose of Google Books “is to make available significant information about those books.” The court held that this purpose is exactly the type of transformative purpose that fair use should enable.

For example: Google Books allows users to track the frequency of references to the United States as a single entity (“the United States is”) versus references to the United States in the plural (“the United States are”) and how that usage has changed over time.

In this way, TDM does not merely supersede the objective of the original work but “instead add[s] something new, with a further purpose or different character.”

Second factor

The court gave fairly cursory treatment to the second factor which requires courts to look at the nature of the copyrighted work, saying that nothing influenced it one way or another with respect to this factor in isolation.

Third factor

For the third factor, the amount and substantiality of the portion used, the court evaluated whether the amount of copying was reasonable in relation to the purpose of the uses. In this case, copying entire works was “literally necessary” to achieve the purpose. If Google copied any less than the totality of the original, the search function would not be reliable. It also noted that Google does not display a copy of the entire work to the public. The snippets of in-copyright text that Google does display are not a competing substitute for the original works.

Fourth factor

Under the fourth factor, the court concluded that snippet display does not give searchers access to effectively competing substitutes and therefore does not threaten rights holders with any significant harm to the value of their copyrights.

The creation of the search index did not make any of the works available to consumers, so it had no direct market effect. The court also considered whether the search index was a “derivative work” that required a license, and concluded it was not. Unlike sequels, film adaptations, and translations, a search index does not “re-present the expressive aspects of the original work.” The transformative purpose of a search index means it is not covered by copyright’s derivative works right.

Conclusions

The Second Circuit held that the Google Books service was a fair use, finding that:

- “The purpose of Google’s copying of the original copyrighted books is to make available significant information about those books,” a different function from that of the original books;

- The amount copied was reasonable to enable the transformative use;

- The amount revealed to users was tailored to the legitimate transformative purpose and did not threaten to substitute for ordinary consumer purchase; and

- The unlicensed use would not cause any harm to a traditional, reasonable, or likely future market for the original work.

Another TDM case: A.V. v. iParadigms

Let’s take a look at another TDM case: A.V. v. iParadigms. iParadigms created a plagiarism detection database of student-authored papers. Teachers could submit student papers to iParadigms, which would check its database for matches and, in some cases, iParadigms would retain the paper for use in checking future submissions. A student, “A.V.,” brought a lawsuit claiming that iParadigms infringed students’ copyrights by using their papers without permission. Citing the internet search engine cases, the Fourth Circuit held that iParadigms’ database was transformative because it was used for plagiarism detection, an entirely different purpose from the term papers. Including entire works was appropriate to serve that new purpose. The use, therefore, was fair.

Lessons learned about key TDM uses

So, let’s review the lessons we learn from the leading cases on TDM when it comes to three core uses that are likely to occur in most TDM research projects: copying to create a database for TDM analysis, using the data derived from TDM analysis, and publishing data sets used in or derived from TDM research.

- When creating a database or corpus, the cases tell us TDM analysis is highly transformative and is strongly favored by fair use.

- The appropriate amount of a work for inclusion in a TDM database is typically the entire work (even millions of entire works), and that’s OK.

- Creating such a database has no market effect, and is not a licensable “derivative work.”

- Derived data does not infringe on the rights of the copyright owner when it consists of unprotectable facts and ideas (like the ngram tool in Google Books). Copyright in a work does not include a monopoly over facts about that work; facts belong to everyone and are free to share.

- Publishing a data set (or excerpts from a data set, as in the snippets from Google Books), requires a separate fair use analysis. Before publishing data, TDM researchers should look at the effects of data publication on the traditional market for the works in the dataset. It’s especially important to consider the amount that will be released publicly and the security measures in place to prevent the kinds of access that could provide a ready market substitute for consumer access to the work.

Fair use mythbusting

The previous two sections in this chapter have addressed what fair use is and how it interacts with activities associated with text data mining. Unfortunately, there are some persistent misconceptions which circulate about what fair use does and does not allow. This section will debunk some of these common misconceptions so you are better informed about what fair use does and does not allow.

Denied permission requests

Myth: An author cannot rely on fair use if she asks for permission and is denied.

Reality: The truth is, you do not have to ask for permission or even alert a copyright holder when a use of materials is protected by fair use. But if you do inquire about permission, you can still claim fair use if your permission request is refused or ignored. In some cases, courts have found that asking permission and then being rejected has actually enhanced fair use claims. The Supreme Court has even said that asking for permission may be a good faith effort to avoid litigation.

Using entire works

Myth: An author cannot rely on fair use if he is using an entire copyrighted work.

Reality: The amount of the work copied is just one factor courts consider alongside the other factors, and in particular courts look at whether the amount used was reasonable in light of the purpose of the use. In some situations, courts have found use of an entire work to be fair. This was the case in the Google Books case examined in detail earlier in this chapter: Even though Google copied entire books when making its searchable index, the court found that copying of the entire work was reasonably appropriate to the transformative purpose—indeed, the court said it was “literally necessary” to achieve the purpose.

Using unpublished material

Myth: An author cannot rely on fair use if they are using unpublished material.

Reality: Congress amended the Copyright Act in 1992 to explicitly allow for fair use when using unpublished works after several court decisions suggested that the use of unpublished materials would rarely be fair use.

A court may still consider a work’s unpublished status to weigh against fair use when evaluating the “nature of the work” under factor two, but this factor is rarely decisive on its own and courts still must weigh all of the fair use factors, including the purpose of the use. The purpose of the use may weigh against fair use if the unpublished material is being used in a frivolous or exploitative manner. On the other hand, the purpose of the use may weigh in favor of fair use if the unpublished material transforms the original material and contributes to the public’s interest in advancing knowledge.

Using highly creative works

Myth: An author cannot rely on fair use if she is using highly creative copyrighted work.

Reality: While courts do consider whether the copyrighted material used is primarily factual or creative under the second factor, “the nature of the work,” this factor is rarely decisive on its own. Courts still must weigh all four factors, again including the “purpose of the use.” Where the purpose of the use is transformative and the amount used is reasonable, the second factor rarely affects the final outcome of fair use cases.

Making commercial uses

Myth: An author cannot rely on fair use if he is making a commercial use of a copyrighted work.

Reality: The truth here is that while “noncommercial” uses may be a plus in a fair use analysis, there are no categorical rules: Commercial uses can be fair use, and not all noncommercial uses will be fair use. In fact, some of the important court victories for fair use over the past two decades have been won by defendants whose activities were commercial, including musicians, publishers, and artists who sell their works (sometimes at substantial prices).

Copyright risk analysis: remedies and risk reducers

The material in this chapter has hopefully helped you feel more confident that you can evaluate copyright questions that arise in TDM research. In particular, you will have overcome perhaps the greatest myth in copyright: that fair use is unpredictable and unreliable. Even with this newfound confidence, it is important to remember that very little in life is certain, and we often have to think about risk and uncertainty in order to act with imperfect knowledge about the future.

Weighing risk using expected value

One way to think about the risk involved in doing a particular thing, popular among economists (and lawyers who wish they were economists), is to think about the “expected value” of taking that action: multiply the magnitude of each outcome’s good-ness or bad-ness (is the result totally awesome or truly terrible, +$1000 or -$100,000?) by the likelihood of that outcome coming to pass (is there a 20% chance this will happen, or an 80% chance?). The sum of the resulting numbers can give you a sense of the overall risk/reward for any course of action.

When you think this way, a few interesting things emerge: if something is really, truly terrible (or really, totally amazing), even a low likelihood of it happening can meaningfully change the overall value of your choice. This can explain the extreme risk aversion that many folks feel as they approach copyright: they have heard about the insanely high penalties imposed on folks for sharing just a few songs online, so even if it seems unlikely that someone will sue you, if they did, you worry that things could go very very badly.

Luckily, the law has several mechanisms that make this bad outcome exceedingly unlikely for researchers and research institutions.

Risk reducers in copyright law

The first is section 504(c) of the Copyright Act, which includes a carve-out that favors non-profit, educational institutions, libraries, and archives, and their employees. When these folks have a “good faith belief” that their reproduction of copyrighted works is fair, courts “shall remit” statutory damages. In other words, only actual damages are available in these cases. (And as we saw earlier, these are likely to be low-to-zero in TDM research cases). Those hefty penalties you may have heard about in file sharing cases are simply not on the table when section 504(c) applies.

Note, however, that this only applies to the reproduction right, which is just one of the several statutory rights in the law. Distribution (sharing copies) and adaptation (creating derivative works) are not covered. So if you are relying on section 504(c) in your risk calculus, think carefully about whether everything you are doing in your project will be shielded.

State sovereign immunity and qualified immunity protect state institutions and their employees against money damages in most cases. The Supreme Court reaffirmed the application of state sovereign immunity to copyright cases in its 2020 opinion in Allen v. Cooper. These immunities will protect state institutions and employees from money damages in most copyright cases, but the court can still order injunctions (judicial commands that the losing party do or refrain from doing particular things). The key remaining risk for state institutions may be that all the time and effort invested in a project could be lost if a court were to find the project infringing and order the resulting data destroyed or made inaccessible pending rightsholder permission. And of course private institutions (even non-profits) are not covered by these immunities. Also important: Congress can waive these protections in cases of willful infringement, if it drafts its legislation carefully. At the time of this writing, the United States Copyright Office is drafting a report on the feasibility and desirability of new legislation to do so.

Another limitation on remedies, which may be helpful in working with archival materials, is that timely registration is required in order to seek statutory damages. While most commercial works (e.g., novels, academic journals) are likely to be registered, other classes of works may be much less so. Amateur works such as snapshots, ephemera and advertising material, and unpublished and archival works all may be less likely to be registered. If your corpus doesn’t include commercially published works, you may face a much lower likelihood of statutory damages.

Risk reducing strategies

Notice and takedown-style policies can give concerned or upset rights holders a channel for expressing their concern, and can give you an opportunity to accommodate them without anyone ending up in court. Hot tip, though: you don’t have to promise to take things down, and it can actually help shape expectations if you frame your notice mechanism in terms that are less negative, like “We welcome you to contact us to ask a question or share information about this research collection.” Anecdotal evidence suggests that responses to these kinds of prompts are more likely to lead to amicable resolutions.

Reasonable attribution is really important to some authors and rightsholders, and can go a long way to avoiding temper flare-ups. Of course, some won’t be placated by this, but surprisingly many folks who raise complaints about content reuse are (or would have been) satisfied by just getting the credit they felt they deserved.

Plaintiffs face risks, too. A recent study found that the average copyright case costs $300k to litigate to a verdict. If a plaintiff loses, courts have the discretion to force them to pay the defendant’s court costs and attorney fees, if the court finds the suit was frivolous or unwarranted. (This is called “fee shifting.”) And the Streisand Effect can mean bad press for a copyright holder who sues sympathetic defendants, like libraries and researchers.

Remember (and weigh) the risk of inaction

Any particular research project may pose a variety of risks, but you wouldn’t consider embarking on the project if it didn’t present an opportunity to do something good. Too often in academia we treat all risk as unacceptable, and ignore the upside value of fulfilling our mission, or, the downside of failing to pursue our mission. The rational course is not to insist on zero risk; it’s to consider both the upsides and the downsides of action and inaction, then make choices that are more likely to do good than harm. As you consider a project through the lens of risk (and develop strategies to mitigate it), don’t lose sight of the value that drew you to the project in the first place, or the loss associated with abandoning the project due to excess caution.

Copyright use case revisited

Let’s return to our case study we outlined at the very beginning—gathering together a dataset of materials of varying copyright status, and allowing users to browse through works in this collection according to the geographical places that are mentioned within them. In this case, a user has searched for “Paris,” which brings up a selection of results where “Paris” is mentioned in text, and that “Paris” has been disambiguated to refer to Paris, France, and not Paris, Texas.

The works that comprise this collection have mixed copyright status—we might be relatively confident that works published in 1925 or earlier are in the public domain, while those published afterward are more likely to still be subject to copyright (unless those authors failed to comply with formalities—such as notice—during that time period). This collection also contains works of fiction—so not just purely factual content, but “highly creative works.”

We can see this use case as being analogous to that of Google Books—we’re performing a transformation of the original (perhaps copyrighted) text in order to present information that’s not directly accessible in any single work (here, using geography as an organizing principle to index the entire collection). We use the entire work for the index that we are creating here, but only present small snippets from the original work (single sentences) to users.

The more complex component of this use case comes in the goal of annotating selections from this dataset (having people mark where in the text a place is mentioned), and then publishing those annotations along with the original texts. This requires its own fair use determination separate from that of the indexing-and-visualization use case; while in the former use case only snippets are published, here we want to publish larger samples of text—perhaps a passage of 500 or 1,000 words from a single novel.

The first question to ask is: do we need to publish anything from the original texts at all? Other alternatives may exist. One possibility would be to only publish the annotations (not linked to the original texts), along with a description of the process by which another user could map those annotations back onto the original text—for example, publishing an annotation that says that word 171 on page 37 in the original work is a “place.” If another user has access to the same copy of the original work, and can follow your process to align an annotation with that work, then publishing the original work isn’t necessary.

In many cases, however, users simply don’t have access to exactly the same copy of the original text that would make reproducibility possible, so let’s consider that the annotations we create need to be published alongside their original work. What do we need to consider when making decisions about the scope of this project? As we’ve seen, there are a number of factors that determine whether this specific case study qualifies as an instance of fair use—so without making a recommendation for this case, we can outline the different factors that would go into a determination. First is the purpose and character of use—in this case, we could reasonably argue that the annotations that we publish alongside the original works are adding new meaning and expression to the original work; we’re not simply republishing parts of the original works alone, but only to support the human judgments of place names we’ve layered on top of them. Second is the nature of the copyrighted work—many of the works in this case study are works of fiction, and so constitute creative works—which (as we’ve seen) would be more likely to weigh against fair use. Third is the amount and substantiality of the samples we are considering publishing—how much can the samples we publish be seen as a substitute for the original, copyrighted work? While the use of entire works may qualify for fair use, one main consideration is whether the amount of the work used is appropriate for the use—and for the task of enabling reproducibility of NER models, a smaller sample (e.g., publishing only 1% of a 100,000-word novel) may be reasonable. And finally, what is the effect of publishing these samples on the market for the original work? We might imagine that publishing a large amount of a contemporary popular work like Harry Potter may impact its sales, while publishing smaller samples that don’t get at the heart of work would not.

So these are some of the factors to weigh when deciding on the design of this project—what data sources to use, and how to best use them to help realize the goals of the project. There is risk in all decisions—for this particular project, we need to weigh the risks of using texts in copyright with the risks of not using them—in this particular case, using texts published after 1925 in a reasonable way enlarges the pool of sources beyond the primarily white and male authors represented in texts published before then. But knowing the landscape of copyright should provide some strategies for weighing and deciding upon these risks yourself.