4 Licensing

Scott Althaus; Brandon Butler; Kyle K. Courtney; and Glen Worthey

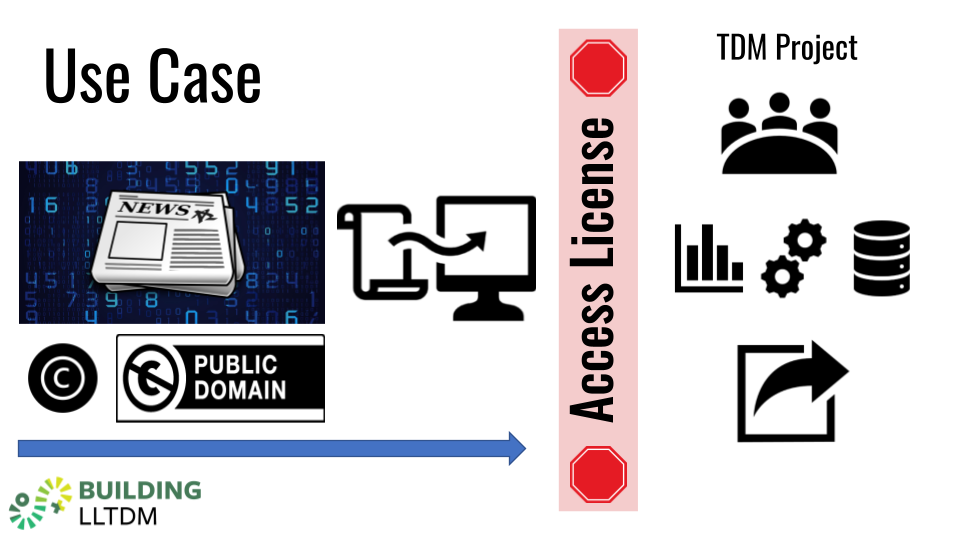

Licensing use case

Let’s identify a use case for you to keep in mind as you are moving through the Licensing chapter.

Let’s say a TDM scholar has a new critical interdisciplinary research project on women’s roles in top 50 corporations in the United States from 1920-2020. For their analysis, they want to create a data file that includes both the text and basic metadata for selected articles focusing on women’s roles from key national newspapers, which also includes coding work developed for the project to mine and index all the information. The scholar believes that the unique dataset they will create via the TDM process, which includes both the metadata and full text of the articles, would be incredibly useful to other researchers studying this same interdisciplinary topic. Because of the scope and range of the timeline, the 1920s through 2020, some of these articles are in the public domain and some are in-copyright.

For those that are in copyright, the TDM scholar can access and hopefully mine some of these articles through their University Library’s licensed resource. These types of databases are commonly sold to a higher education market by a vendor that has a relationship with major newspapers and collects, indexes, and provides full text access to these newspaper articles that are historical in nature.

However, some of the articles will be accessed and mined via a subscription agreement. The TDM scholar has an online subscription to this newspaper, and receives daily emails featuring the day’s articles. Additionally, one national paper in particular that was the subject of some of the scholar’s research provides access to the historical newspaper articles via a separate agreement, which is not part of the daily circulation agreement.

The scholar wants to mine these newspapers, develop the coding, and publish this dataset, with the selected articles in full text, as a public-use file.

This might be a very familiar scenario. As we will review, a license or contract is an agreement between two parties to specific terms. A license or contract can modify, change, or alter rights.

And while the licensing of digital content exists in a legal realm that is separate from copyright law, they do interact—as they most likely will in this scenario or any TDM scenario.

Now, please take a moment now to reflect on this scenario. What issues do you see arising? What are some factors identified that will benefit this work? What might require more explanation or negotiation? How would you begin to strategize in understanding any risk on the use, input, and output of the data and full text?

Contract & licensing basics

While we read about copyright and fair use in the earlier chapter on copyright, the second step is to determine the details of access to the materials. Many different contracts and agreements govern access to copyrighted materials and define what particular uses a researcher may make of these materials.

As we explored a bit in the use case, a strategic question to ask when you are beginning to be involved in a TDM project is: How will you access this material? The answers will vary. Some access will be via a library-licensed resource, which is sometimes part of institutional wide access. Some access might be through public facing websites featuring terms of use, and other access might be through an individual subscription which had an agreement that you clicked on to access.

Contract law is about enforcing promises. A contract is a promise or a set of promises for the breach of which the law gives a remedy, or the performance of which the law in some way recognizes as a duty. Licenses are most often granted within the context of a contractual relationship and often the same words used to create the license are also contained in the same instrument that also memorializes a contract. A license is a “contract not to sue.” For our discussion, then, a license or contract is a legal interest created by a titleholder granting use-privileges to some non-titleholder. We will use the terms “license” and “contract” interchangeably.

So, as you can imagine, contract and licensing agreements can determine what a TDM researcher can do within legal bounds. Many of us will never have to write a contract from scratch. Trust us, this is a good thing! However, we do want to explore the underlying contract and licensing system so that you have some context for the parts in the legal process that makes a contract or license valid.

The first is the offer. The offer is where one of the parties made a promise to do some specified action in the future.

Second is consideration. This is where something of value is promised in exchange for the specified action or non-action. This can take the form of a significant expenditure of money or effort, a promise to perform some service, or an agreement not to do something. Consideration is the value that induces the parties to enter into the contract.

Third, we have acceptance. The trick is that the offer has to be clearly accepted. Acceptance may be expressed through words, deeds, or performance as called for in the contract.

And last is mutuality or “meeting of the minds.” It is necessary that the contracting parties had “a meeting of the minds” regarding the agreement. This means the parties understood and agreed to the basic substance and terms of the contract.

Beyond the legal requirements, there are also several contract provisions that are standard.

- The Parties. Definitely be sure you are naming the correct parties. And, this is a good area to look for in case you take the permission route or need to contact the right person or party. The publisher, vendor, or database might have one name, but the legal party to the contract—the corporation or person that has the rights—might be listed there, with a different name.

- The Overview. It is a mistake not to at least consider drafting, asking, or including an overview or purpose. Think of the overview as a chance to tell parties (and third parties viewing the contract) what the contract is about in a few paragraphs. This could help other users down the road that have to interpret this contract or license.

- Payment section. As stated before, consideration in the formation of a contract can be simple—a payment, for example. If it is complex, you can refer to the contract section that sets forth other consideration: scheduling, quarterly payments, or per-use payments might be listed here.

- The Date. This is often overlooked. Be sure the date of execution by each party is included so that there will be a time at which the parties became bound to the contract. And, this may be related to when the agreement “starts the clock” if it is a limited timeline or subject to renewal based on this date.

- The signature. Print or digital is acceptable.

Boilerplate clauses are often standard, and most are not typically heavily negotiated. But they are important. Many contract disputes depend on the drafting of boilerplate clauses such as termination, force majeure, and entire agreement.

Why are they important? Most likely, the TDM project you are dealing with will have boilerplate language—even if it’s a closed or open license!

Types of licenses & contracts

In the last section we mentioned boilerplate. The opposite of a boilerplate clause is one which is written and expressly addresses the desired outcome.

For the next few examples, we will look at TDM contact language utilized in the NERL Consortium Generic License Agreement and the Liblicense Model Agreement. These are drafted as ready-to-apply provisions that could work with a variety of licences and could be incorporated into a standard authorized agreement with a vendor.

These clauses specify uses that are familiar to most TDM work and directly address the needs and issues that arise.

Note that this selected language is integrated into the document using the same uniform language as the original contract, including defined and capitalized terms such as Authorized Users, Licensor, and Materials.

Note also how the clause outlines the limits, defining the purpose of the use as different from the protected commercial market.

Occasionally, you will get pushback in proposing these clauses. Always be sure to have a backup clause or justification for TDM or related clauses. For example, the fees provision that is listed at the top of the example below is rejected, you might, as suggested by this model Liblicense Agreement, limit or categorize the fees with the bullet points listed below. Always be ready with another clause if you can:

Licensor shall provide to Licensee, upon request, copies of the Licensed Materials for text and data mining purposes without any extra fees.

- OR: If the licensor insists on referencing fees, they should not exceed the cost of preparation and delivery

- OR: If Licensee or Authorized Users request the Licensor to deliver or otherwise prepare copies of the Licensed Materials for text and data mining purposes, any fees charged by Licensor shall be solely for preparing and delivering such copies on a time and materials basis.

And that’s some of the difference with boilerplate and negotiated clauses. While you can’t change boilerplate, you can negotiate with these TDM specific clauses.

Now we focus on some of the most common types of contracts.

Non-negotiated licenses

Non-negotiated licenses are typically associated with major publishers and online resources. They are filled with the generic boilerplate terms, and, additionally, as the title states, do not typically accept any negotiated terms. In easy terms, this license is called “take it or leave it.” The non-negotiated licenses default uses license terms that are biased in favor of the licensor. Again, they offer little room for changes or addendums to attach to the contract. TDM is certainly new enough of a field to have been completely left out of any previous access or purchase licenses, although we will discuss some places they do exist in other sections or language.

Non-negotiated licenses can also come in the form of a common mass market license (like in software or vendor products) and click-wrap or browse-wrap. Sometimes they are part of a more generalized public license, which will be covered in a later section of this chapter.

A librarian or researcher is forced to weigh the non-negotiated license provisions as part of the cost-benefit analysis of assenting to the agreement. The key question is what may be forbidden under this document that I actually need to do for my scholarship or project?

Click wrap licenses

Click licenses have many names: click-through, clickwrap, splash screen, or even click-to-accept contracts. But many of us are well-familiar with this type—we all have probably downloaded an app and checked “I agree” without reading the license. All of these are a type of license where a user must expressly assent to a non-negotiable unilateral agreement by clicking a button displayed next to or below a statement. The button does most of the work here: it asks the user to accept or agree to the proposed contract terms. In some cases a licensor will use a checkbox and/or scrolling mechanism to let the user view or browse through the entire agreement and to make sure you have scrolled to the bottom before clicking the button. A quick side note: this scroll through method does not ensure that the user actually read the agreement —it is just one method to get the user to at least scroll through it.

Despite the fact that many users do not read the text, these agreements have been upheld by both state and federal courts, provided that the text preceding the acceptance button makes it clear that a user is accepting the terms of a contract and not merely signifying readiness to proceed to the next screen, at least where it is clear about the terms. The user consents to these conditions by clicking on a dialog box on the screen, which then proceeds with the transaction.

Two factor authentication (for example, texting a code in response to a click) is used as well. This is called incorporation by reference. It shores up the legal argument that the actions were sufficient to establish express assent to the Terms and Conditions in the agreement.

Occasionally, there is a basic link to the terms which reside elsewhere. Either way, the check or click is the assent to the terms of the agreement.

However, if you are concerned about certain clauses or terms affecting TDM and you do want to read and not click right away—and we’d highly recommend that—there are some key sections to look for where TDM related clauses may reside. One is certainly a section on “Authorized Uses” or “Permitted Uses.” Note that occasionally there will be a section on non-permitted uses or restrictions. Moreover, the definitions section occasionally even defines TDM right there. And finally, TDM-related clauses may be found in any sections listed as “Intellectual property” or “copyright.” The TDM-related clauses are typically found in some or all of these sections.

Browse-wrap licenses

Browse-wrap licenses are another type of non-negotiable, unilateral contract where express assent is not obtained. These licenses are typically a static display of the terms and conditions (or “Terms of Service”) for the resource. And usually it is presented through a hyperlink or language in the footer. This indicates to the user that by using the resource, you are bound by those terms.

These browsewrap agreements may be enforceable, but only if assent or a “meeting of the minds” may be fairly implied based on the conduct after a user is put on actual or reasonable notice that access or use is subject to these terms and conditions. Courts have even looked to see if the conduct could be continued use of or access to the website, database, or service. Or the conduct can be identified that the user downloaded the product.

Interestingly enough, a study by two law professors in 2019 found that 99% of the 500 most popular U.S. websites had terms of service written as equally complex as an academic journal article, which makes them, possibly, inaccessible to most humans.

Here’s a quick negotiation strategy: If you are creating or negotiating parts of a license with a TDM project, seek to include language that the license agreement has precedence and prevails over any click-through license on the licensor’s site and that any proposed language for a click-through license is approved by the licensee prior to implementation. Some licensors give you a license, but then link to other terms in some other URL somewhere else that you are also bound to—and sometimes these terms are different or confusing because they may be generic and not specific to the TDM License.

Again, if you have concerns, look for the sections on “Authorized Uses,” the definitions section, sections listed as intellectual property or copyright. The TDM-related clauses usually live in there, or in parts in all of the sections.

Open and public licenses

This section covers open and public licenses.

Public licenses are “boilerplate”—a term introduced you to in an earlier section of this chapter—meaning (very roughly) that they’re non-negotiated. These are licenses under which copyright holders may choose to release their works for use by the public without requiring special permission.

Probably the most famous public license—really, a suite of licenses—is the famous Creative Commons licenses.

Some people believe that Creative Commons is somehow the “opposite” of copyright, or that it somehow negates copyright. That is not the case: copyright in a work is generally an automatic right (as long as that work meets a few very specific criteria). Copyright doesn’t require registration, doesn’t require a little “C” in a circle, and it remains in force until its term ends.

But what an open public license does is to provide a mechanism for copyright holders to grant to “the public” permissions to use their work. The copyright holder relinquishes some of the rights to which copyright law entitles her. It’s a license—as we’ve put it before, a “contract not to sue”—between the copyright holder and the public, for particular uses of a work that would otherwise be restricted, and violations of which could be litigated.

To reiterate what we’ve learned in previous segments, licenses (and other contracts) operate in a separate legal realm from copyright. The don’t undo or modify copyright, but rather (in an interesting sort of turnabout) they actually rely on the copyright holder’s exclusive economic rights in order for others to do something interesting with their works: for example, to choose not to make money from their creations, or to choose not to prevent redistribution or derivative works.

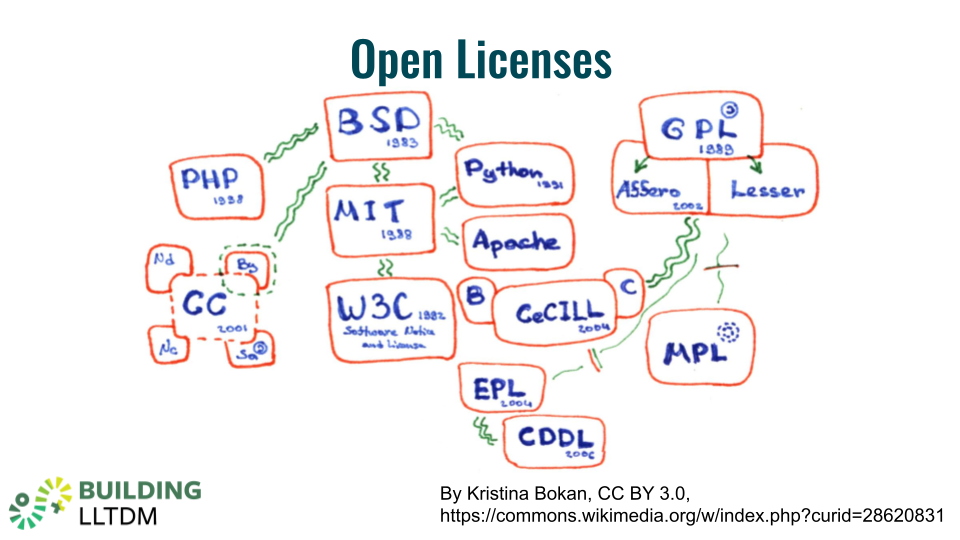

The world of public licenses is immense! Even an important subset of that world, the realm of open licenses, is immense! The chart below illustrates the tremendous variety of the “network of open licenses,” and a sort of genealogy and chronology of their development. We won’t spend much time on their myriad flavors and nuances, but let’s talk briefly about a few of them, starting with the example of the very image you’re looking at now.

This illustration is a copyrighted work. It has an author, Kristina Bokan, who holds the copyright to her creation. But she has granted the public a license to use it—and look how helpfully she’s done so, highlighting (in broken green outline, near the left-hand side of the chart) the specific license she has chosen for it. It is under these terms that she is allowing all of us—including you!—to use her work. This license is her “contract not to sue” us for our reuse of her work—without us even having to ask her—and it’s our contract with her to acknowledge her as its creator. We do this by including her name on the slide.

These two agreements represent the totality of our mutual agreement. We didn’t negotiate it: she set the terms herself, and we accepted them simply by using her image in this chapter. With this interaction, our contract is settled and enforceable. Kristina can’t take away our right to use her cool chart, and we are obliged always to give her credit for it—which of course, as responsible users, we would always do anyway.

“Copyleft” and software licenses

Let’s focus briefly on one corner of this chart, highlighting one family of licenses sometimes called “copyleft.”

Many readers will be able to decipher many of the words denoting the licenses you see here (listed in roughly decreasing order of decipherability): Python (the currently popular programming language), Apache (the software that runs most of the world’s web servers), and W3C (the World Wide Web Consortium).

MIT stands for precisely the great university that you probably think it stands for. And the B in BSD stands for the publisher of this resource, UC Berkeley; the SD in BSD stands for “Software Distribution”—which is the key to what unites these open licenses: they’re all generally used for software, as you might have guessed.

By the way, GPL here stands for the “General Public License of the Free Software Foundation’s GNU Project. (And GNU stands, recursively, for “Gnu’s Not Unix.”)

In addition to the self-referential GNU acronym, note also the hard-to-translate pun implied in the term “copyleft,” which implies that it’s the opposite of copyright. In fact, it’s not: it’s just another license, very much dependent on copyright law (as we’ve noted repeatedly). A creator’s exclusive right to define and determine the terms of use for her creation—even these very permissive terms—is the product of copyright, even when her intent is to manipulate (and in many respects, to undo) many of those terms.

Software licenses are pretty much like licenses for other kinds of content, like texts and images. But one of the distinguishing features of “copyleft” licenses is that they tend to include terms that explicitly allow derivative works, and they tend to require those derivative works themselves to be distributed with the same “share-alike” terms—which makes some sense given their origins. It was precisely the peculiarities of working with software that inspired this particular community to be so activist in creating and promoting open licenses in the late 1970s and 1980s: unlike a book or a record, software begs to be tinkered with: debugged, modified, copied, and so forth. And the copyright regime, together with the restrictive licenses that made billionaires out of many copyright holders, seemed an impediment.

Creative Commons licenses

But maybe it shouldn’t be said that software is “unlike a book or a record” in its desire to be modified and remixed. One of the hallmarks of the next major phase of open licensing, Creative Commons, is the idea of “remix culture” popular in the 1990s and 2000s, and trumpeted by the founder of Creative Commons himself, Lawrence Lessig. That’s our next topic.

Lessig created and began promoting these licenses through the Creative Commons Foundation just over 20 years ago. He has written prolifically (and highly readably) about the origins and philosophy of Creative Commons; about its particular importance in the Internet era; about “remix culture” and “free culture”; and about other aspects of this contract-turned-movement too many to discuss here. It’s interesting and important work, even for non-lawyers.

In practical terms, Creative Commons licenses have a veritable smorgasbord of options that modify the blanket permissions granted by the licensor (that is, the copyright holder). These options can include the requirement that every use be accompanied by an attribution, as with CC-BY; or that only non-commercial uses are allowed; or that disallow derivative works (translations, etc.); and a number of others. Strictly speaking, because of the possibility of these restrictions, these licenses are considered by some people not to be open. For others, that interpretation is a little too fundamentalist: these licenses are specifically designed to make copyright-protected content more open, even if that openness may have some terms attached to it. Even more importantly, these licenses are considered open by many because, by their design, any use not strictly prohibited is actually allowed—no questions asked, no lawsuits threatened, no money changing hands.

Thinking back to Kristina Bokan’s helpful whiteboard chart, has she granted us any other permissions with her CC-BY license? Certainly! With this license, we not only can use her image in this chapter, we could also include it in other presentations and publications without asking permission—we could even just republish and re-distribute it by itself, without adding anything of our own! Likewise, Kristina is allowing us to translate her chart into another language, or set it to music, or use it in a collage; but if she had chosen a Creative Commons “No Derivatives” license, we would not have the right to do any of those things under the license.

Could we put it on a bunch of t-shirts and coffee mugs and sell them? Absolutely! Do we have to ask her permission? Would we owe her any royalties? No: she has already decided this question just by choosing this license. And if Kristina were opposed to that sort of thing (and many reasonable people might be), she could simply have chosen a Creative Commons “Non-Commercial” license and refused to have her creativity feed our crass commercialism. But she didn’t do that.

Open licenses in TDM

What do open licenses have to do with Text Data Mining? Like any other contract, these licenses imply at least two parties, a licensor and a licensee—and people in the TDM community, whether as librarians or other practitioners, have opportunities to act in both roles.

So far we’ve mainly discussed the licensee role: what we’re allowed, or not allowed to do with materials that have some sort of open license applied to them.

But it’s also critical to understand that we ourselves often act as creators—and thus as copyright holders—and therefore that we also have the right to determine the license and the terms under which we allow our work to be used. It won’t surprise any reader of the present that we authors would encourage you, to the extent possible, to choose open licenses. Our libraries can and should do this with the research materials that we create; and scholars can do the same.

Let’s look briefly at an important example of open licenses in the TDM community: the HathiTrust Research Center, and its “Extracted Features” dataset, a staple of TDM work. Although it’s used in text mining, here’s a remarkable thing: it doesn’t actually contain any “text” as we normally define it! Instead, it consists solely of metadata about the texts contained in the massive HathiTrust Digital Library, all 17+ million volumes of them—including a substantial number (about ⅔ of the total) of in-copyright books.

This metadata, naturally, includes descriptions of each book, like any library catalog. But much more significantly (and radically, and intelligently, in our view) is that it includes metadata about each page, each line, each word, and even each letter and each number in those texts. This is all many text-miners need to do their work.

Even though many uses of the texts described by the Extracted Features data may be restricted or proscribed by copyright, because this metadata consists only of facts about these texts, it is not a violation of copyright for the HathiTrust Research Center to extract them or to share them with others: in fact, as we’ve already heard hopefully more than once (but it always bears repeating), the courts have found that precisely this sort of use is a fair use.

But this dataset itself, as a compilation of information with a particular arrangement, an apparatus, and documentation, all of which HathiTrust devised itself, is in itself a newly authored work whose copyright belongs to HathiTrust—which could, in theory, claim all sorts of rights for itself and restrictions for other people. But of course they don’t do that! In order to promote its adoption and use (and reuse, and experimentation, and so forth), they’ve published it under a Creative Commons license.

This is sort of like alchemy: they’ve turned massive numbers of copyright-restricted (or at the very least, ambiguously protected) texts into free and open research materials—and then of course have shared that treasure by being free and open with its presentation of this dataset. This is not some legal loophole, but rather a conscious and conscientious legal innovation based on a solid understanding of the law. Amazing, isn’t it?

Examples and case studies: Library e-resource licenses

Having revelled a bit in the glories of open licensing, let us now turn to some specific examples of private, non-open contracts and licenses that are often highly relevant to TDM practitioners: library e-resource licenses.

This section is based largely on some practical, real-life examples of library licenses as they relate to TDM. They’re not all pretty, but we hope they’ll be instructive.

The world of library licensing for e-resources can seem both complicated and shrouded in mystery. Often this is just a matter of the complexities of back-office library acquisitions processes (selecting, negotiating, signing, paying, getting access, setting up authentication and proxy servers, etc.), and the related feeling that nobody except those directly involved really needs to know how this particular sausage is made.

Non-disclosure agreements

But sometimes this mystery is intentional: many licenses, and the negotiations leading up to their signing, are specifically subject to non-disclosure agreements (“NDAs”). These NDAs are imposed by vendors who don’t want libraries to compare the supposedly “great deals” they’re being offered with deals offered to other libraries. (Some might find secretive price-setting to be a legitimate business practice, although in this particular practice, the prices paid for the very same product by different libraries, and the discounts and “great deals” offered to them, can vary to such an extent, and be so irregular, that the entire pricing regime seems to border on the fictional.)

However, many people find NDAs fairly pernicious for other reasons as well, especially where the non-price terms are concerned. As we’ve seen, license terms can often drastically curtail some very important rights in areas of scholarship like TDM. There has been a movement in universities to ban the entering into contracts subject to NDAs, and several of us authors have been made proud and happy when our universities have done that. The particular example license terms about to be used as illustrations may have come before the NDA ban, but vendors’ identities have been obscured just in case.

Adventures in commercial licensing to libraries

As described above, licenses are a form of contract: in particular, a “contract not to sue.” But library licenses for electronic resources generally have a substantial set of terms—terms that are consequential to TDM work—long before anyone gets to the point of suing!

We should care about these licenses for at least two very important reasons: one is that they are, broadly speaking, licenses governing our right to read (including the specific type of reading to which this workshop is dedicated: text data mining as reading). Another is that we are all bound by these licenses when we read (or use in any way) the texts that make up the e-resource—whether we know it or not.

And yet, how many non-librarian scholars or students do you think have ever seen, or thought about, or even know of the existence of these licenses? In our experience, not very many: even among library workers, it’s rare that someone outside of a very few acquisitions people, or a special licensing librarian, has ever seen them!

How many people in the campus community generally even know that they’re bound by the terms of a license signed secretly on their behalf by some librarian they don’t know, a license that they didn’t agree to, and haven’t even seen?

To engage in some stereotyping, we’ve seen several different categories of reactions among users of library-licensed e-resources. The vast majority is largely apathetic: they don’t know and don’t care, and that’s generally okay: their use of e-resources is pretty well covered by pretty much any license that the library may have signed on their behalf.

Among readers who are interested in more than simply reading these licensed works—say, those engaging in TDM—there is probably a broader (but no less problematic) range of knowledge about their licenses, for example:

- Bold ignorance: the savvy grad student who knows how to script and how to scrape, and generally believes that, if whoever put this stuff “on the web” didn’t want them to scrape it, they wouldn’t have made it so easy.

- Or fear: scholars who don’t even bother asking for TDM access, because “what if someone gets into trouble?”

- Or even outrage that we librarians have agreed to a license that forbids them from doing TDM-based research.

Difficulties

Some people, both practitioners and scholars, may experience a deep dreariness as part of the license reading experience. But in case you’re tempted to escape from an e-resource license back into the comfort of volume 3 of War and Peace or the multivolume classic of your choice, we’d like to posit that there are some truly important and not at all uninteresting bits of text here, at least not uninteresting to readers of this text. In spite of the difficulties experienced by non-lawyers reading legalese, we would encourage you to ask around your libraries to find and talk to the people who negotiate and maintain licenses, because they’re so important to what we all do in the TDM community.

You might think, with so many lengthy, carefully crafted pages of strict legalese, that library licenses would be water-tight bastions of hard-and-fast terms and conditions. But far from it! Every license is a product of imperfect human authors, sometimes a long line of them inheriting prose from predecessors, on both sides of a complex purchasing and licensing transaction, and they merit multiple close readings because, as we’ve said above, they have real consequences.

Here are few passages from an actual e-resource license (underlining in the original; bold added here for emphasis):

6. Data Mining. Subject to any content-specific restrictions, Customer and its Authorized Users may extract and compile data from locally-loaded copies of the Purchased Content for Customer’s teaching, learning, and research purposes

[…]

9. Restrictions. Except as expressly permitted above, Customer and its Authorized Users shall not:

[…]

i) Text mine, data mine or harvest metadata from the Service…

This license, from a major library vendor, seems to include two distinctly contradictory terms on the very same page! The first one, allowing that “Users may extract and compile data” from the resource, seems expressly to permit data mining. But the second one seems expressly to prohibit it.

Not only are many of these licenses dense and difficult to read, they’re also, often, a real mess. But with practice, even non-lawyers can easily learn to spot problematic terms and try to eliminate them through negotiation. There’s a sample of problematic licenses in the Readings section of this text, along with a good model license (which we’ll touch on in a few minutes) for comparison.

Negotiation

Once we understand that a license is a voluntary contract, there are some important aspects to the licensing process that can play in our favor: complementary interests. For example, the vendor has a commercial interest (it wants to make a sale), and the library and its scholars have an academic interest (they want access to the vendor’s content). So although we may have competing interests in the price, we really have common interests in finding agreeable terms.

Unfortunately, many library vendors either don’t yet understand TDM practices, or overestimate their importance to an extent that leads them to believe libraries might be willing and able to pay a premium for TDM rights. Likewise, many of these vendors are third parties, selling content that they themselves may have licensed from an actual copyright holder, which obviously complicates matters. And naturally, the easiest and safest position for a vendor to take is a restrictive one.

But it’s essential to push back. While we don’t have any special tricks to offer for negotiating licenses, we do strongly believe in a couple of principles: first, the right to read is the right to text-mine, and it’s a right we should never willingly sign away. Some have advocated for the inclusion of a simple escape clause in our licenses, along the lines of, “notwithstanding any of the foregoing, nothing in this license should be interpreted to prohibit fair use of the licensed materials.” Since the courts have ruled that TDM is generally a fair use, this clause should, in theory, provide blanket permission for TDM activities.

The second principle is to maintain the clear position that one of the primary affordances of electronic texts is, in fact, the ability to read them with a computer—that is, to do TDM. If the only allowable uses of a digital text are basically the same uses that we could make with print books (many of which we have in our collections anyway), why on earth would we spend these huge sums of money for an electronic copy? Mere convenience of access is not worth the premium that some vendors put on their electronic resources.

Finally, for all of these reasons, it’s crucial to be prepared to walk away from negotiations and decline a purchase if the terms aren’t right.

Model licenses

But these days, there’s no need for anyone—vendor or library—to draft a license completely from scratch. In fact, it’s better if they don’t! One important innovation in recent years is the “model license,” which various research library consortia have developed and adapted as an expression of what the library research community considers reasonable expectations for licensing terms. The Center for Research Libraries, NERL (the NorthEast Research Libraries consortium), and the California Digital Library all offer model licenses that are available to all—vendor and librarian alike—to use as references, sources for terms, or even straight-out adoption.

The California Digital Library’s model license has—no surprise—particularly good terms for TDM, including both explicit mention of TDM as an authorized use, and a fair use “escape clause.” Here’s a snippet of these simple, powerful terms (underlining in the original; bold added here for emphasis):

Text and Data Mining. Authorized Users may use the Licensed Materials to perform and engage in text and/or data mining activities for academic research…

[…]

Licensee and Authorized Users may make all use of the Licensed Materials as is consistent with United States copyright law, including its Fair Use Provisions.

These model licenses are important for several reasons: not only do they lighten the load of drafting from scratch, but even more importantly, they set general expectations that are broadly shared by the TDM research community. For example, the CDL model license presents as a given that research libraries expect to have text data mining rights—and particular kinds of terms—in their vendor licenses. In this way, vendors (many of whom have historically been quite unfriendly to the whole idea of text mining) are put on notice that academic expectations with regard to TDM rights are now clear, and that these are terms that our community, in growing numbers, expects and will demand.

This and the other model licenses we’ve mentioned are incredibly important resources, both tactically and strategically. Because they originate in the academy, they’re favorable to academic uses—unlike commercial licenses, which are generally written from a strong protectionist instinct and with commercial interests foremost.

Although we advocate taking a tough TDM stance with vendors in the negotiation of licenses, we should emphasize that there’s real value in establishing and maintaining good relations with them: vendors have something that we want and need, and they exercise control over it, whether we like it or not. It’s worth remembering an influential 2018 blog post by our co-author Brandon Butler, whose title says most of what you need to know: “For Text and Data Mining, Fair Use Is Powerful, but Possession Is Still 9/10 of the Law.”

Breaches and consequences

In our experience, the consequence of not having good TDM license terms—or not exercising them if we have them, or not informing our communities about them—is that scholars inevitably find ways to get, or to attempt to get, the data they want by web-scraping or by some other systematic means that are often explicitly prohibited, and can have unpleasant consequences for both the vendor and the offending library (and beyond). This has happened frequently enough in our collective library experience that we suspect it’s a fairly widespread occurrence—but it doesn’t have to be that way.

The most immediate consequence of a vendor discovering what it considers to be illegal downloading is to shut off access to the entire campus. With good vendor relationships, these consequences have been temporary: librarians have been able to track down the offending (and often unsuspecting and well-intentioned) party, and offer an explanation of why a particular activity is prohibited. In an ideal situation, the librarian can propose a license- or fair use-enabled alternative to the prohibited methods. Given a solid relationship, the library is able to reassure the vendor that the prohibited activity has ceased, and the vendor will generally open things up again. (Remember that even the most rigidly license-enforcing vendors actually want us, above all, to resubscribe to their products.) This is a real hassle, but relatively minor in the scheme of things. It’s better to negotiate clear terms up front.

Another reason to establish and maintain good relations with our vendors, aside from simple human decency, is so that we can confidently approach them with requests for special access or data deliveries for use by our researchers. It has been our experience that vendors will do their best, against tradition and their protectionist instincts, to honor the request, and to give their customers what they need.

There’s obviously much more to be said about library licenses, but we hope these examples and this discussion will encourage you to approach licensing thoughtfully, boldly, and without too much fear or loathing.

Websites and terms of use

The CFAA: Is scraping a public website illegal hacking?

One concern that may arise in connection with scraping public websites is whether there are any legal repercussions in addition to potential breach of contract when scraping is inconsistent with website policies. Website operators have tried to use federal anti-hacking law—in particular the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act—to add teeth to their terms of use. The CFAA bars any “unauthorized” access to any “protected computer,” which courts have said means essentially any machine connected to the internet. The most high-profile CFAA prosecution in recent years was brought against the free culture activist Aaron Swartz, who downloaded millions of research articles from JSTOR by circumventing security measures at MIT. Federal prosecutors charged him criminally for violating the CFAA, but were roundly criticized (along with JSTOR and MIT) for their aggressive pursuit of the case. Nevertheless, website operators have argued that any access to a site that exceeds the site’s terms of use is “unauthorized,” which should trigger CFAA liability.

Luckily, the clear trend in the courts in recent years has been to reject this argument, at least for public websites. Two recent cases illustrate the point. In hiQ Labs v. LinkedIn, the data analytics company hiQ was accused of violating the CFAA by scraping public LinkedIn profiles after being ordered directly by LinkedIn to cease and desist from scraping. The Ninth Circuit ruled that “authorization is only required for password-protected sites or sites that otherwise prevent the general public from viewing the information.” The case has been appealed to the Supreme Court, which hasn’t yet agreed to hear it as of the time of this writing.

In Sandvig v. Barr, the ACLU brought a challenge to the CFAA on behalf of journalists and researchers who planned to use scraping as well as fake profiles and other deceptive practices to probe whether employment websites were discriminating against some users. This is a well-established way for journalists and investigators to uncover discrimination, but the terms of use of these sites prohibit providing false information. Can site proprietors use federal anti-hacking laws to insulate themselves from discrimination probes simply by changing their terms of use? Citing hiQ, the district court found that CFAA does not apply to scraping public websites (among other behaviors), and should only apply when a user bypasses an authentication mechanism, such as a password restriction, designed to ensure that only certain, authorized individuals have access to the site.

Use case: The Twitter API

The Twitter Developer policy, agreement, and terms, which govern access to data via the Twitter API, are a good example of a robust, enforceable contract governing a commonly-used source of research data. The Twitter API makes it easy to retrieve massive amounts of data from the Twitter ecosystem, but Twitter tightly regulates how that data can be used and, especially, how it can be shared. The Twitter API Terms create a strong, enforceable contract by ensuring that anyone who participates is required to clearly signal their assent, and only permitting access to those who have created an account and assented. Twitter makes special allowances for scholarly use, but even academics are prohibited from sharing large corpora of full-text tweets. The detailed provisions in the Twitter API, including distinctions between “Tweet IDs” and full-text content, warrant a close read by any researcher working with the API. It’s clear that Twitter takes these terms seriously, and violating them could land you in hot water with the company, a political problem that could be very damaging for a researcher who relies on Twitter data for their work.

Use case: Digitized library materials

Even material digitized from library collections—even public domain material!—can be governed by tricky terms of service. For example, much of the digitized collection in the HathiTrust corpus was created in partnership with Google, and limitations on reuse were part of that arrangement. Accordingly, HathiTrust (and member libraries) uses an Access and Use policy to ensure that users don’t do anything that would place them in breach of their agreement with Google (or otherwise create liability for HathiTrust or its members). Additional terms of use govern the HathiTrust Research Center’s TDM tools. These terms are designed to ensure that HathiTrust and its users remain within the bounds of what fair use permits.

Another example of a context where library materials may be governed by terms of use is collections digitized in partnership with a vendor like Adam Matthew or ProQuest. It is very common for these materials to be in the public domain, but because they are rare and may not exist in digital form anywhere else, it’s possible to keep them behind paywalls and monetize access. To make that model work, vendors typically require users to agree not to download collections in bulk, or share them publicly, among other things.

Some libraries, museums, and special collections impose their own terms of use on materials they post online. Sometimes the goal of these terms is just to ensure that the library or archives receives credit as the source of collections material. Other times, the institution is trying to guard against liability (or political embarrassment) for itself by ensuring users don’t do anything untoward, or at least documenting that it took steps to warn or constrain users. As libraries move to make their collections more accessible and useful online, more and more are removing all restrictions on public domain materials.

Beyond the terms of the license

So far you’ve learned how licenses work as contracts, and you’ve seen some different kinds of licenses you may encounter in the wild. You know that if you’re accessing content subject to a license agreement, the terms of that license may affect your ability to do TDM research, even though copyright itself is TDM-friendly, thanks to fair use. Now we’re going to look at some of the legal questions you can ask about a license, other than “What’s in it?” These questions include:

- Am I bound?

- How does this license affect fair use?

- What happens if I breach?

- What on Earth is “trespass to chattels”?

- And finally, how to manage risk.

Bound by (contract) law: Privity

The word for someone bound by a contract is “privity”—if you’re “in privity” with the other parties to a contract, you’re bound by it. If not, you’re not bound. How do you know if you’re “in privity”?

As you learned at the beginning of this series, a contract requires both offer and acceptance. And to accept a contract, you need adequate notice of its terms.

If a contract mechanism fails, you won’t be in privity. With non-negotiable contracts, especially online and digital ones, there is still substantial controversy about when and how these agreements can bind users. Some “browsewrap” licenses (where the terms of an agreement are linked from a notice on a website, often in small print at the bottom of the page) have been ruled unenforceable in court because users didn’t have adequate notice of the terms, or a meaningful opportunity to affirmatively accept (or reject) them.

Other contexts where a user may not be bound by a contract include “downstream” users of resources subject to license. Consider a second-hand user who obtains data not directly from the publisher but through a colleague or intermediary. It seems unlikely that someone in that scenario can be bound by terms they never saw and never had any opportunity to accept. Similarly, someone who acquires a copy of a work on the second-hand market—used software or other media, for example—may never be presented with adequate opportunity to accept the relevant terms.

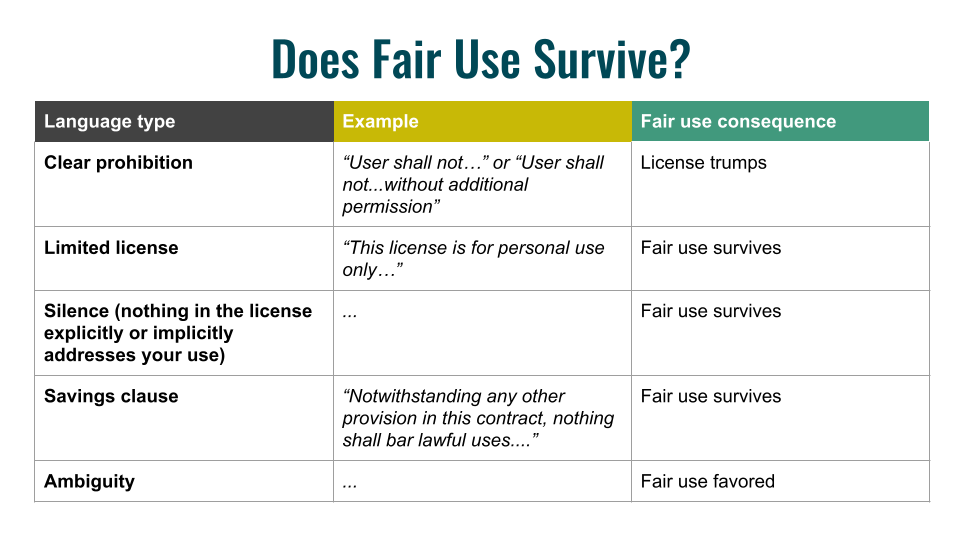

Licenses and fair use (and other user rights)

Some people who work with licensed materials, including lawyers (unfortunately), come to believe that the license is all that matters when it comes to figuring out whether and how licensed collections can be used. A license is “private law” that the parties make for themselves, after all, and the parties can (and often do) agree to abridge the default legal rights they bring to the table, as part of the bargain. If a contract is a legally enforceable promise, it’s easy to see how someone could promise not to exercise fair use, for example. But depending on the contract, you might NOT have made that promise, in which case, fair use (or another default legal right) will survive.

Instead of thinking of the presence of a contract as necessarily nullifying fair use, you should imagine contract law and fair use rights as separate sources of authority. You can seek permission (a license) to use a covered work, OR you can exercise your own rights under the law. If the copyright holder withholds permission, that doesn’t necessarily undermine fair use. Indeed, it had better not, because fair use JUST IS the right to make certain uses without permission. Whether fair use survives a license will depend on the specifics of the contract.

Here are some common types of provisions that can occur in license agreements, and their likely effects on fair use. As you can see, far from always nullifying fair use, there are many circumstances in which fair use survives a license.

Language of clear prohibition or a promise not to engage in certain uses is most likely sufficient to surrender fair use rights. An example of clearly prohibitory language is “User agrees not to…” or “User shall not…” This is a promise by the user not to exercise her fair use rights. Licensors commonly use this kind of language to ensure users do not engage in bulk downloading or redistribution.

Language describing the limits of a license, such as a statement that a particular license is “for XYZ use only,” (e.g., “for personal use only”), should be read to leave fair use intact. That language tells you how far the license goes, but it does not tell you that you may not rely on fair use to go further. It may be that the licensor would be unpleasantly surprised by uses that exceed the license, and you may factor that into your risk calculus. However, fair use is by definition a use that the rights holder cannot control simply by withholding their consent.

Contractual silence about a particular fair use activity should also generally leave fair use rights intact, by the same logic. But be careful: if you promise not to do certain things that are necessary predicates to your fair use (e.g., large-scale downloading from a database), that promise will effectively prevent you from engaging in fair use.

The best case scenario is a fair use “savings clause,” which is increasingly popular as a strategy for libraries negotiating licenses. These clauses will typically say something quite broad, like, “Nothing in this agreement shall bar users from making lawful/fair uses of licensed materials.” An agreement with this kind of clear, broad savings language lets you ignore contrary language elsewhere in the agreement as long as your use is otherwise lawful and fair.

When a contract is ambiguous, there are several reasons a court or other interpreter might favor fair use. First, fair use is a right with constitutional underpinnings; waiver of such rights must typically be clear and unambiguous. Second, contracts, especially non-negotiated ones, are typically interpreted “against” the author of the agreement. This is because these contracts place so much power in the hands of the contract drafter, courts are wary of permitting them to use ambiguity to their advantage. Instead, they force licensors to be as clear as possible to place other parties on adequate notice of the terms, or else risk losing any dispute over the terms’ meaning.

The stakes: Remedies and consequences of breach

Remedies for breach of contract are typically much less severe than the toughest copyright penalties. Licenses present a mix of copyright and contract issues, and violating a license can trigger copyright liability. But remember: failing to abide by a license isn’t copyright infringement unless your use requires a license. In other words, if your use is a fair use, then breaching a contract is only a breach of contract, and nothing more.

The most likely negative outcome is one the licensor can impose unilaterally on your institution: shutting off access to the resource. Licensors don’t have to go to a court to enforce the terms privately by terminating access in this way. And because some TDM research can resemble a serious security breach, vendors may be more likely to quickly shut down access in response to unexpected TDM-related activity. If your institution disagrees with the vendor, they could threaten to sue the vendor to get access restored, but that’s an expensive proposition. The more likely outcome is that you and your institution will have to negotiate with the vendor to have access restored. In the meantime, other researchers who need access to the resource will be frustrated.

Trespass to chattels, or, why you should scrape nicely

One last issue to consider, especially when scraping public websites, is trespass to chattels. Trespass may be more familiar in the context of land, but trespass to chattels is unreasonable interference with the ordinary use of someone’s personal property.

A paradigm case of trespass to chattels online is a DDOS attack, which barrages a server with so many inquiries that the server becomes unusable for its ordinary purpose. Automated scraping or web harvesting activity could trigger a trespass to chattels claim if it took place in a time or manner that interfered with the vendor’s ordinary use of the server. Event promoters like Ticketmaster have brought trespass claims successfully against scalpers who overburdened their servers by using bots to buy tickets.

The best way to avoid this kind of claim is to be polite when you scrape. Don’t hit servers hard, especially during normal business hours.

Risk management

How can you lower the likelihood of something going wrong, and how can you lower the stakes and reduce the impact in case something does go wrong?

One thing to consider is reaching out to the copyright holder/licensor and getting additional or more specific permissions. Experiences diverge wildly, but vendors are increasingly familiar with TDM and may well be amenable to negotiating specific terms to permit it, even if their standard contract does not. As you may have learned in the copyright chapter of this book, being told “no” doesn’t hurt your fair use argument—and may even help you.

Another way of controlling risk is to be polite in your use of licensed resources. As we mentioned in discussing trespass to chattels, a lot of good will can be won by scraping, downloading, or otherwise accessing content in ways that don’t interfere with the ordinary use of a licensed resource. Ill will and risk, however, go up quickly when your TDM-related activity looks like a security breach or piracy.

Finally, be available and responsive when folks have concerns. If you share your data, include a way to be in touch with you. If someone reaches out, don’t ignore them. Do what you can to make it easy to channel any objections or concerns quickly and easily into a low-impact resolution.

Creative ways to work within licensing boundaries

Despite the challenges of navigating the range of licensing issues that ethical TDM researchers need to traverse, many researchers have found creative ways to work within the boundaries of what is allowed that open up more opportunities for ethical research than might be apparent after a first glance at licensing terms. What follows summarizes a recent publication on this topic co-authored by one of the authors of this chapter with the unusual title of “The Trouble with Sharing Your Privates”. If you enter that title into Google Scholar there is only one that will come up—it’s easy to find.

We start with the standard way of thinking about legal boundaries, of which the main umbrella categories are copyright law and contract (or licensing) law. Copyright law can be thought of as a national-level entity and contract (or licensing) law can be thought of as an organizational-level constraint.

Collaborating with researchers in other places presents a special set of compliance challenges. What happens when you have collaborators in different countries: which set of copyright provisions apply? Or what about collaborators who are in different universities: how to navigate the licensing issues for team members who may be bound by different licensing restrictions? Raising these difficult questions with legal authorities in your campus often results in a discouraging answer, given the scale or institutional risk for such a collaboration. Yet there are a number of ideas that those legal authorities may be unfamiliar with that might be legally compliant with many licensing restrictions.

Short-term solutions

There are some short-term solutions that might respect legal boundaries. We want to underscore “might” here because every license is different and researchers will have to check which among these might be compliant with the legal boundaries in each particular situation. The first is using non-consumptive or non-expressive research modes. The Hathi Trust Research Center (HTRC) provides extracted feature access to the entire HathiTrust book corpus. HTRC allows for access to extracted features such as entities, sentiment scores, token counts, and verb counts. All of this is pure information that exists apart from expressive uses of text, so working with extracted features violates no expressive use and may be compliant with many licenses.

A second possibility is publishing metadata and extracted features that allow your collaborative team to actually find the full-text content on their own, through their own licensing regime. Metadata for a typical newspaper article includes the title, the author, the date of publication, the source of publication, and so on. Often collaborators in other places can use that metadata to track down where they can get access to the full-text content within their current licensing regime. And sometimes it’s easier than that. It is possible to construct Lexis-Nexis metadata into URLs that include unique 16-digit identifiers for specific pieces of Lexis-Nexis content. If a researcher is in an institutional setting with licensing that is compliant with access to that content, dropping that URL into an authenticated web browser will magically reveal the full-text content. Researchers in institutions that don’t have proper licensing access will get a “404: File Not Found”. This is just one way to share full text data by exchanging only metadata.

A third possibility is providing remote access to compliant computer systems. A researcher might set up a virtualized server that resides in an institution that’s bound by its licensing agreements, and ensure that any licensed data always stays on the hard drive of that compliant physical server. What’s different in this model is that users can be brought to the data from other countries and other institutions just as easily as users from across your own campus. If the user remotes-in and accesses licensed data that always stays on that server, that is a model that might comply with an otherwise restrictive license.

The fourth possibility is publishing or sharing small validation data sets. Random samples of larger corpora published under fair use provisions (if that would apply) would allow collaborators to develop and refine their algorithms that they want to run on the larger corpus. When they’ve got their algorithms up to speed and producing the kind of output that they want, they send those algorithms over to the researcher with licensed access to the larger corpus, and in a compliant manner that algorithm could be over the entire corpus. So long as the resulting extracted features or similar output violates terms of copyright or licensing, it should be possible to deliver the resulting set of extracted features back to the originating collaborators.

A last possibility is bringing collaborators from other locations physically to the campus or institution that holds the licensed data in order to work together face to face. Most campus licensing provisions for library materials have a cutout for visiting scholars. Bringing somebody physically to your location often gets them full access temporarily to the same content that any researcher at that location has licensed access to.

Longer-term solutions

There are also some longer-term solutions that the TDM community would do well to explore. One is building more collaborative open data sets like the Linguistic Data Consortium at Penn that allows—for a very small and reasonable licensing fee—access to full-text data that can be shared across national jurisdictions. There’s also Amazon’s AWS Common Crawl, which is freely-available web content at very large scale. Licensing might apply even to freely-available data, so it is important to check that such data can be appropriately used for a given research context. Another model is Wikipedia: a lot of content out there can be mined and shared within Wikipedia’s permissive licensing.

A second longer-term solution is to advocate both within our institutions and within our professional associations for better data agreements that have clearer terms, that have more expansive allowable uses for research purposes, that give us clearer boundaries so that we can know what we can and what we can’t do but that also respect the important need for researchers to have relatively free and broad access to sensitive, in-copyright materials.

A third option is solving a local problem. When researchers want to do something that’s outside of what everybody locally already knows how to do legally, they often end up talking with somebody in front of a desk where the answer’s going to be “No” because nobody’s quite sure exactly who’s got the final authority to make the call. Encouraging our campuses to develop a “buck stops here” position—call this a data ombudsperson—who is empowered to make that final decision can simplify the process of getting research done in a timely and efficient manner. A good data ombudsperson would know what you’re allowed to do with text and what you’re not allowed to do, would know the legal landscape, would understand the licensing, and could calm people down who might be a little bit concerned about what a researcher wants to do. Empowering such positions will open up broader opportunities for scholars and students to do expansive and innovative text data mining research in more reasonable timelines than they might otherwise be up against.