6 Ethics

Stacy Reardon; Rachael Samberg; and Timothy Vollmer

An overview of ethical considerations in TDM

How can digital humanities researchers incorporate an ethical framework into text data mining? Privacy protections, which are primarily legal mechanisms, will only get us so far. As Todd Suomela and colleagues wrote in Applying an Ethics of Care to Internet Research: Gamergate and Digital Humanities,[1]

“Humanists are not used to thinking ethically about research subjects because we mostly deal with either subjects who are dead or subjects that are public figures like authors, politicians or other humanists, whose roles and activities are open to scrutiny and debate. The real or potential harms inflicted by research methods on these subjects are often intangible and hard to measure.”

We will explore two key ethics questions by surfacing theory through case studies and scholarly literature.

First, we learned in the chapter on privacy that when “public” data is being collected and republished for TDM purposes, it isn’t necessarily protected by privacy statutes. So, in the absence of privacy law requirements, to what degree of care should we treat TDM data?

Second, if the current regulatory framework for research involving human subjects is set up to protect privacy, how do we know when to impose an ethical framework? And when and how do we balance the application of a framework with truth-seeking, the public interest, and free expression?

Public, but sensitive

So what do we do with data that is not technically private, but we feel might be sensitive?

As we saw in the Gamergate research mentioned above, the bringing together of public social media messages can serve as a signal boost for hate messages and misinformation. The mere act of compiling these Tweets makes these messages and the targets of the messages more easily discoverable. Yet in many cases, there is nothing private in this data, at least as far as privacy is defined by state and federal laws. But aggregating these hateful messages can also boost the signal concerning views about which an author later has changed their mind. So we have to ask, what is our responsibility as researchers?

Second, should we somehow account for the fact that creators of data might not understand what is protected by privacy law, but might think that data they make available online should essentially still be treated as private? After all, it has been repeatedly demonstrated that the average user’s expectations of “privacy” don’t necessarily match with what the law says. So do researchers bear an obligation to adhere to social norms or ethics to protect it?

Mismatched expectations are a particular problem when data crosses international boundaries. Many big data research initiatives are international, and protections vary substantially depending on which national data protection regulation applies. Research subjects may believe that the regulations of their home country protect their personal data, when in fact the requirements of another jurisdiction could apply once the data crosses a border.

And third, how do we approach secondary uses of data that are not intended or predicted by their creators? For example, novelists did not expect for their words to be converted into data. But as Effy Vayena, et al. write in Elements of a New Ethical Framework for Big Data Research,[2] many individuals do not understand the permissible secondary uses of information deemed to be public. In addition, website terms of service do not necessarily help inform people about potential secondary uses. So even setting aside the fact that authors may have had a different expectation of their audience or the ultimate uses of their writing, they also might not realize what they consented to in posting to a public platform.

Take the Please Rob Me[3] project as an example of all these harms. Please Rob Me collected information about people’s locations from both FourSquare and other social media posts. In 2010, the website demonstrated how users can inadvertently share information that compromises the security of their home by aggregating public tweets from users. The content in the posts suggested that the user was not at home. In this case, the purpose of the website was to raise awareness of the potential for real-world harms, but it is easy to see how this concept could be exploited by bad actors. Even though the information about where people were at the time was public, people’s expectation of “privacy” were colored by how obscure they viewed their social media account to be. If another individual mines Twitter accounts for a certain type of information and aggregates and links the information to the accounts of these users, then search cost has been dramatically reduced. The question arises: How should we account for this in TDM research design and publication?

Decontextualization

One contour to consider in deciding how to protect sensitive information is the notion of decontextualization. Below is a photo an Instagrammer took at a restaurant when she ordered avocado toast. The picture and the accompanying article are meant to be a tongue-in-cheek commentary on the value of contemporary restaurant cuisine. But if we were to only look at the photo itself, which includes a piece of toast, half an avocado, lime, and cheese placed separately on a platter, what do we need to be able to understand that this Instagram post is supposed to represent avocado toast, rather than its deconstructed parts?

This image highlights part of the problem with the use of public yet sensitive data: the use of the information for research purposes is potentially stripped of important context or narrative. Not only can this cause personal harm to the author, but in some cases can perpetuate harm to historically marginalized populations. As Kimberly Christen has explained, discovery replays a colonial paradigm, where content is imagined as unhinged from peoples and cultures and free for the taking.

She writes,

“One can quite easily get content from a Google image search, scrape it from a website, or download it from an academic digital archive. The process is imagined as a neutral act—one of taking something that is already offered up for consumption. But this notion of ‘data mining’ offers a telling example of how colonial legacies of collecting physical materials from local places and peoples are grafted onto digital content. Content is imagined as open, reusable, [and] disconnected from communities, individuals, or families who may have intimate ties to the materials.”[4]

Again, the law does not stipulate a way to account for decontextualization.

Structural racism and power imbalances

In addition to decontextualization, another factor to consider in deciding how to protect sensitive information in TDM research is the unequal power structures that enabled its creation or collection. Here, we can observe that data collectors and researchers may be in a greater position of power than the data generators—that is, the people who actually create the information, or from whom the information is collected.

This is a problem for a consent-based ethics framework because underprivileged groups may lack either the knowledge of how information about them will be used, or the ability to intervene in that usage. The World Intellectual Property Organization, or WIPO for short, has tried to develop international frameworks to protect communities not just from having their traditional knowledge exploited, but also to protect them from overstudy and from not receiving the benefits of the research in some meaningful way.[5]

There is a tension, here, though, in that intellectual property laws and human rights frameworks are focused on individual rights, and not group rights. In an article, legal scholar Ruth Okediji explains that absent a fundamental shift, the current types of rules will not facilitate realization of the economic, social, and cultural benefits envisaged and guaranteed by group rights. And without a move toward group rights, it is not really possible for marginalized communities to have real freedom to create, use, and enjoy knowledge assets. Okediji argues that a move toward group rights “strip[s] away any pretense of neutrality and permit[s] scrutiny of, or legal challenges to, private laws with distributive implications that undercut the ideals of human progress and development.”[6]

In the absence of a group rights legal framework, we exist in a universe of determining whether and how to seek individual consent for research. Now we’ll turn to what a consent-based ethics framework means for TDM research.

The research consent framework

As explained in the previous section, to answer some of our questions about whether and how to protect sensitive but not private content, we have to dig into the research consent framework.

Let’s imagine that our TDM researchers want to feel like they’re doing the right thing by obtaining consent from the creators of the TDM content they’re using. And let’s also imagine that our TDM researchers are in luck, because they’re mining data from a platform like Twitter, through which content creators have already expressly consented to their content being used downstream—merely by using the site.

As Vayena et al 2016 found, even if consent is given for re-use in the terms of service (TOS) for a social media site, because the details are often buried within the lengthy text, users are likely unaware that they have consented to human subjects research through their use of a mobile or social networking platform alone. For instance, Twitter’s TOS permits individuals to distribute, Retweet, promote or republish tweets on other media and services.[7]

Users’ reliance on TOS that are vague, complex, and subject to modification without notice leaves users with an incomplete understanding of how their personal information will be used and shared, and arguably fall short of the informed consent requirements intended by research ethics and regulatory frameworks that were developed for clinical research.

Research by legal scholars Kate Crawford and Jason Schultz raises procedural due process considerations. They ask,

“[H]ow does one give notice and get consent for innumerable and perhaps even yet-to-be-determined queries that one might run that create “personal data”? How does one provide consumers with individual control, context, and accountability over such processes?”

Some uses—including the retention of data for longer than originally envisioned, or for use under a different purpose—may be unforeseen at the time of collection. So, how can it actually be considered consent—and thus how can due process have been served—if one cannot have even conceived of the queries that one might run relying on personal data?[8] This is the very reason some scholars are moving away from the consent-based research paradigm, which emerged in the 1970s, to a harms-based paradigm.

From obtaining consent to avoiding harm

Another reason scholars are advocating for a move from a consent framework to one based on treating “harm” is because a consent-based regulatory framework for human subjects research is not conducive to TDM. The current regulatory framework is based on the Common Rule, which outlines ethical rules regarding research involving human subjects.[9] The Common Rule was heavily influenced by the Belmont Report, written in 1979 by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research.[10] In 1981, with this report as foundational background, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) revised, and made as compatible as possible under their respective statutory authorities, their existing human subjects regulations.

The Common Rule is implemented in Title 45 of the Code of Federal Regulations, pertaining to Public Welfare, and falls within the Department of Health and Human Services.

For all participating federal departments and agencies, the Common Rule outlines the basic provisions around informed consent and assurances of compliance that are subsequently implemented by Institutional Review Boards (IRBs). Human subject research conducted or supported by each federal department/agency also needs to conform to additional regulations of that department or agency.

The Common Rule is porous

The general problem is that the Common Rule—which requires obtaining informed consent—is often inapplicable to common TDM methodology. Typical human subjects research must go through an institutional review board. But many TDM studies in the humanities fall outside the Common Rule’s reach where there’s no direct interaction with subjects or studies that involve subjects’ private, identifiable information. Therefore, institutions are not required to oversee the research at all, even if you may feel there are ethical concerns.

Let’s get even more specific about why the informed consent framework creates gaps in research oversight. What qualifies as human subject research—and thus subject to purview of Common Rule and IRB review—is perhaps too narrowly defined because it is concerned with situations where 1) a researcher is collecting information through an intervention or interaction with a subject or 2) identifiable private information is involved. We often don’t have either of those two conditions in TDM. First, conducting TDM doesn’t necessarily occur with an intervention or interaction with a human subject. Second, TDM doesn’t necessarily involve private information. In addition, de-identification can nominally render the Common Rule/IRB inapplicable, even though doing so has been shown to be an ineffective means of preserving privacy; a research dataset that has been de-identified can in many cases be used in combination with other data to re-identify someone.

Professional guidelines don’t necessarily answer the questions about ethical conduct for TDM. The British Psychological Association and Association of Internet Researchers recommend careful consideration of ethical issues when using social media data with particular regard to privacy, but the guidelines do not take an overt stance on the matter of consent for publication.[11]

Even assuming TDM researchers want to apply Common Rule standards and gain informed consent, this isn’t always feasible when the data collection is from inordinately large numbers of people.

Also, obtaining consent may not be possible because the very notion of “authorship” may not be aligned with a particular proposed use. As Kimberly Christen explains: “In western settings (and legal contexts), the author is seen as the sole creator of a work […] In many Indigenous communities, however, the notion of a single creator of a song or author of a narrative is undone by value placed on community production, ancestral creation of stories, or other forms of cultural and artistic content […] No one person can or would assert authorship or ownership of the materials.”[12] It may flow from this that no one person can give consent.

Given what we know of the consent-based framework, and the gaps in oversight it leaves for much TDM research, how should we proceed with an ethical theory and practice? We’ll begin to explore that in the next section.

Ethics theoretical frameworks

As we have discussed, even public data that we wish to use for TDM research might include sensitive information, data decontextualized from the context in which it was created, or data created or used through methods enabled by structural racism or power imbalances. Obtaining explicit consent for such data is one response to negotiating such concerns, even though consent may be unnecessary from a regulatory perspective since the Common Rule typically does not apply to TDM research. Even so, consent may not always be feasible for a variety of reasons. In those cases, we might consider a move from a consent-based ethics framework to a feminist ethics of care.

Here, we briefly consider philosophical underpinnings of three ethical frameworks for conducting research.[13] Imagine you have the capacity to help someone in need. Furthermore, helping them would not diminish your own capacity. Should you provide this help?

- A deontologist would recognize an obligation to help in accordance with a moral rule such as “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.”

- A virtue ethicist would act based on the fact that helping the person would be charitable or benevolent.

- And a utilitarian will point to the fact that the consequences of doing so will maximize well-being for the greatest number of people.

Each of these normative ethical frameworks places emphasis on moral responsibility and the agency of the individual. Although moral agency assumes free will, power imbalances necessarily complicate the notion of choice or free will. Unequal power structures shape the creation or collection of data. Data collectors and researchers may be in a greater position of power than those of their subjects or of content creators. (This is why, for example, The World Intellectual Property Organization has tried to develop international frameworks to protect communities—not just from having their traditional knowledge exploited, but also to protect them from overstudy and from not receiving the benefits of the research in some meaningful way.) This is potentially a problem for TDM research because those represented in the data may not have had free will in how the content was originally created or collected, or they may not have agency in determining how that data is used downstream (such as being used in TDM research). Furthermore, the “distributed morality” of big data—also referred to as “dependent agency”—means that the ethics of data use in a networked framework may be dependent on the morality of other actors in that network, or even on the structure and limitations of the technological infrastructure itself.[14] For these reasons, an individual consent-based framework may not always be enough in guiding ethical decisions.

Ethics of care

An alternative ethics framework might help here. Ethics of Care—also known as Feminist Ethics—is premised on relationships and care as a virtue. This framework recognizes uneven power relationships. Projects adopting an Ethics of Care approach build into their research design an accounting for who possesses power or authority in a given situation.[15] Through its focus on relationships, an Ethics of Care framework also enables a progression from accounting for the rights and obligations of individuals, to the rights and obligations of groups.

Like utilitarianism, Ethics of Care endeavors to avoid or at least minimize harm. In “What’s the Harm? The Coverage of Ethics and Harm Avoidance in Research Methods Textbooks,” Dixon and Quirke[16] identify four categories of harm:

- Psychological harms (referring to participants’ well-being, and inclusive of things like distress, embarrassment, stress, and betrayal of trust)

- Physical harms (this would include physical pain, injury, and death)

- Legal harms (this includes legal implications from exposure — imagine here photos of underage drinking, being seen at a protest against a tyrannical government and facing potential action, or depiction as a migrant subjecting one to potential deportation.); and

- Social harms (these include damage to relationships, social standing, or reputation — and would include impacts on personal and employment relationships through the disclosure of information)

Dixon & Quirke observe that the research ethics textbooks they reviewed failed to treat ethics continually or holistically throughout all stages of the research process. Instead, they approached ethics as a one-time consideration, with a focus on avoiding harm during data collection. However, as they note, “ethical issues permeate and unfold beyond the research design stage and throughout the entire research process.” While textbooks may focus on ethics at key moments, such as obtaining informed consent, we might advocate for ethics to be considered throughout the research lifecycle. Moreover, taking into account the network of relationships that compose any project as well as the lifecycle of the project, we might well ask if we need to expand our idea of whose wellbeing beyond that of the research subject should be of concern to us. The Belmont report is set up to protect research subjects, but as we saw from Suomela’s Gamergate case study, his project also considered potential harm to the research team. Accordingly, we may wish to apply our ethics framework to all research stakeholders, including researchers and readers.

When considering potential for harm, we might implement a “do no harm” approach or one that seeks to minimize rather than eliminate the potential for harm. The latter may require a risk-benefit analysis of possible harm. In “Elements of a New Ethical Framework for Big Data Research,” Vayena et al. (2016)[17] advocate for big data researchers and review boards to incorporate systematic risk-benefit assessments. These assessments would evaluate:

- the benefits that would accrue to society as a result of a research activity,

- the intended uses of the data involved,

- the privacy threats and vulnerabilities associated with the research activity,

- and the potential harms to human subjects as a result of the inclusion of their information in the data.

The decision about whether to proceed with the research based on these balanced factors is not binary. Researchers will have to make informed but difficult choices about the best way to proceed. We will explore examples of researchers who attempt to apply a risk-benefit analysis in our next section.

To summarize, we noted that while there is a lack of established best practices when approaching ethical considerations in TDM projects, we can contribute to this evolving discussion. Different ethical frameworks for approaching these issues include deontological, virtue, or utilitarian models, or a feminist Ethics of Care. We might consider different types of harm, such as psychological, physical, legal, and social, and we might consider the different groups in the research lifecycle who could experience such harm, whether those be subjects, fellow researchers, or consumers. Ethical considerations are not just one-time judgments, but extend throughout the research process. Our ethical framework may lead us to adopt an approach that prioritizes doing no harm or one that seeks to weigh harm through a risk-benefit analysis.

Research applications of ethics

We will now review examples of a few research teams who attempted to apply ethical considerations to their TDM projects.

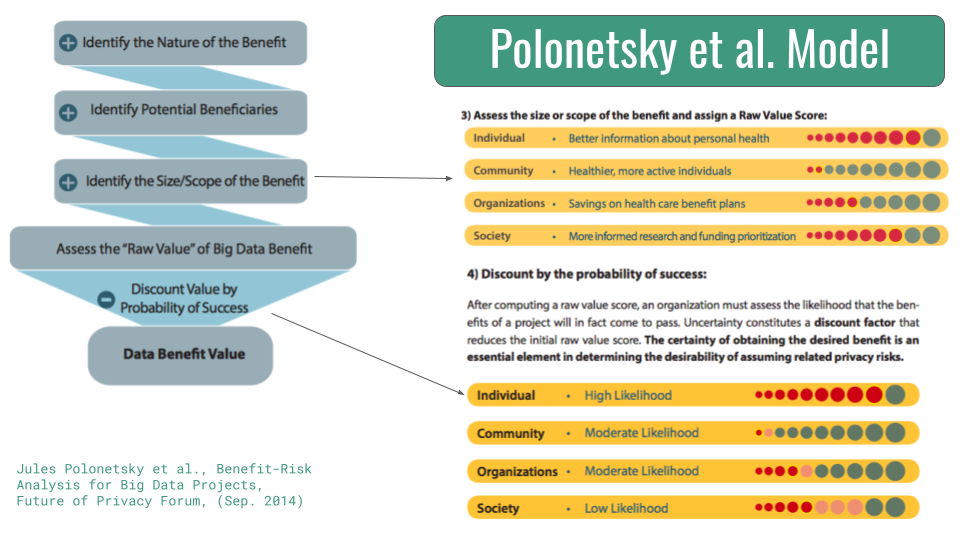

Polonetsky et al.’s (2014) “Benefit-Risk Analysis for Big Data Projects” is one model for operationalizing such a risk-benefit analysis.[18] The Polonetsky model identifies the panoply of benefits of the proposed data project, along with all potential beneficiaries.

They then determine the size and scope of potential benefit to each of the beneficiaries to weigh the raw value benefit of the project. This is represented at the top right of the image, with higher value for a stakeholder measured in increasing numbers of red bubbles. That raw value benefit then gets discounted by the probability of success for each of those beneficiaries — the bubbles you see on the lower right. This yields a discounted data benefit value.

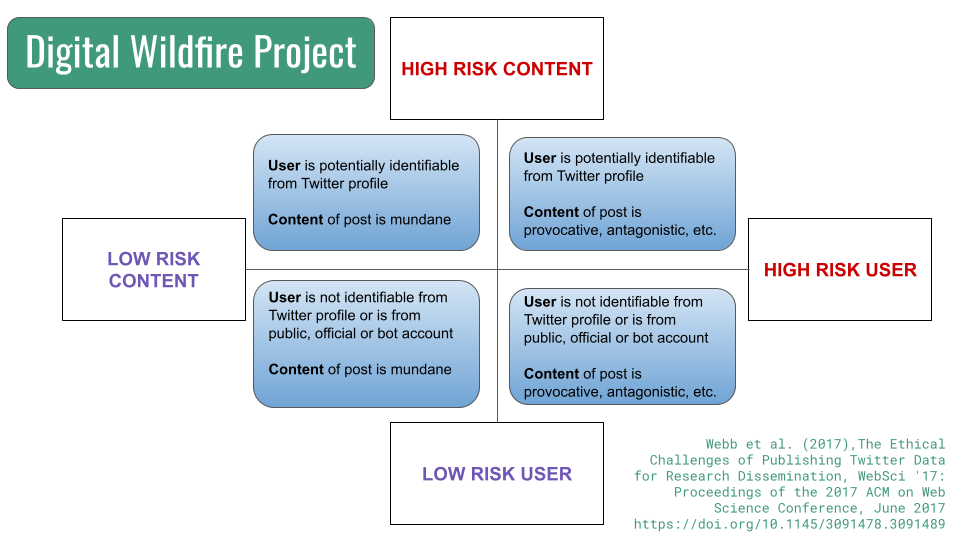

Another approach to addressing harm according to a risk-benefit assessment is illustrated by Webb et al. (2017) in their paper on the ethical challenges associated with the Digital Wildfire Project.[19] The Digital Wildfire Project sought to identify opportunities for the responsible governance of digital social spaces by tracking how social media platforms such as Twitter offer the capacity for inflammatory, antagonistic, or provocative digital content to spread on a broad and rapid scale.

Given that the project included examination of hate speech, there was concern that harm may come to identifiable users who posted content considered to be hateful or inflammatory. The researchers queried whether, from an ethical perspective, they needed to contact the user and solicit informed consent to republish the tweets. Further, there was concern that the re-publication of tweets might cause victims of hate speech harm in addition to the harm they experienced when the content was originally posted.

To determine how to proceed, the researchers reviewed relevant guidance, expert opinion, and current practice. There was no consensus from any of these sources. Accordingly, the research team attempted to develop a consistent way to balance value and risks. The graphic depicts the resulting risk grid mapping high/low risk users and high/low risk content.

Nevertheless, they were unable to reach consensus about how to address potential harms or apply a risk-benefit analysis, nor could they draw firm conclusions about best practices with regard to republishing the tweets. Since no one had any answers, they felt the “best practices” for navigating these concerns might revert to local researcher ethical considerations.

This lack of community guidance could be seen as a challenge, or an opportunity for us all to shape the landscape of legal ethics in this area.

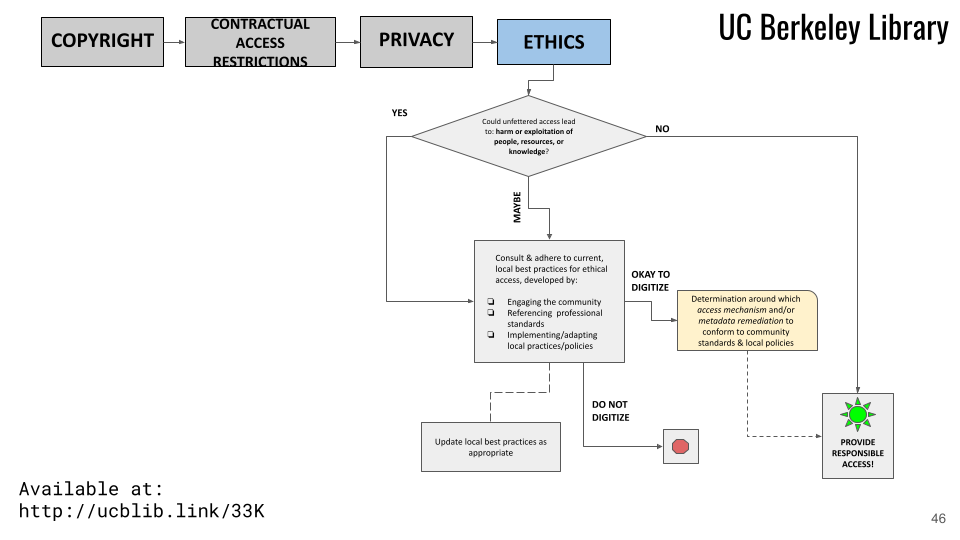

We’d like to highlight one final example of how we at the UC Berkeley Library are trying to implement a harm balancing approach for materials we digitize and make available for TDM projects. Generally speaking, our local ethics best practices would be implemented when providing unfettered access to a collection or materials could potentially lead to harm. They may also be invoked for already digitized content when the Library considers requests pursuant to the community engagement policy, or otherwise becomes aware of situations in which materials in our digitized collections may create harm.

To develop these policies, the Digital Lifecycle Steering Committee[20] charged a group of librarians and archivists with expounding upon the definitions and underlying actions that would constitute our local best practices for ethical access to digital content. Our working group conducted a review of relevant literature addressing ethical approaches to digitization in libraries and archives; definitions and treatment of harm and exploitation in law, international policy, and professional literature; empathy and human rights; indigenous knowledge and sovereignty; and the European concept of the right to be forgotten. We found The American Philosophical Society’s Protocols for the Treatment of Indigenous Materials to be particularly inspiring and instructive, and much of the format (and some language) for our protocols is based on APS’s blueprint.

Our working group expects the local ethics best practices to be finalized in the fall of 2021 following additional community engagement work. As currently conceived, our local ethics best practices ask whether the value to cultural communities, researchers, or the public outweighs the potential for harm or exploitation of people, resources, or knowledge.

- When referencing objects, materials, or resources: We intend “harm” or “exploitation” to encompass the following:

- economic disadvantage to the interests of a cultural community (such as unfair competition, or commercial appropriation);

- violation of customary or national laws, or the established practices of a cultural community; or

- risk of looting or defiling of cultural sites or resources.

- When referencing people: We intend “harm” or “exploitation” to encompass:

-

- A deprivation or violation of, or credible threat to, a person’s liberty, body, or well-being.

-

These definitions were informed by the four types of harms Dixon and Quirke recognized. We then developed a set of principles for how to assess both value and potential harm, similar in intent to what Polonetsky et al recommended, but focused on guidelines rather than formulas. For instance:

- We give added weight to potential value where there is a strong public interest in the material, considering factors like: the content is about public figures; information is about communities, society, or political issues; content is self-authored; the content is composed of government documents or journalistic documents.

- We give added weight to the potential for harm where

-

- Content impacts cultural communities historically disadvantaged by power structures

- Material is about the community/creator rather than by the community/creator

- Community/creator had or has less ability to control the information

- A takedown request was made

This approach makes use of an ethics of care framework that seeks to minimize harm. Less prescriptive, it establishes general guidelines that allow local decision makers to weigh benefit vs. harm, ideally in consultation with community representatives and local experts.

In this section, we have looked at a few examples from research teams who have wrestled with ethical considerations in big data. Polonetsky, et al developed a formula for a risk-benefit analysis based on the scope of benefit to different groups and the likelihood that each group would receive those benefits. The Digital Wildfire Project attempts a risk-benefit analysis for Twitter data, but instead of proposing their own best practices, they recommend that local practices inform judgment. The UC Berkeley Library is working on ethical guidelines for the provision of digitized materials that ask whether the value to cultural communities, researchers, or the public, outweighs the potential for harm or exploitation of people, resources, or knowledge.

Strategies to address ethical concerns

Over the previous sections, we’ve come across examples of strategies to approach ethics within TDM research. We characterize these s strategies because there are no actual best practices yet for dealing with sensitive information that is not technically “private” under the law. We hope that you’ll begin to think about TDM ethics within your own situation, and start to develop a set of norms and risk management strategies that will allow you to proceed with your research with confidence and relative clarity.

We have loosely organized the following strategies in ascending order of the effort or difficulty in undertaking them. This collection is not meant to be exhaustive; you might have other ideas for strategies that will be applicable in your research situation.

- Consult journal publications or professional association guidelines. But as discussed above, these may not get you all the way to the question you’re trying to answer.

- Develop local best practices (for instance, you could conduct decision-making within your research group, as the Gamergate research team did,[21] or we did at UC Berkeley for digitizing our collections).[22]

- You could impose access controls (e.g. user registration to view; publish only data visualizations or extractions), but you’d need to consider the intersection with any publisher open data requirements.

- Undertake community engagement to consult with affected populations, and ensure that benefit reverts back to the communities.

- Seek IRB involvement/approval, even if none is technically required. Of course getting IRB review & approval for research that ordinarily doesn’t need approval can slow down the research process (and overwhelm IRBs), so some fundamental structural changes at your institution might be needed.

- Adopt a new ethics/privacy paradigm (for example, moving from consent-based to harm-avoidance)

- Unless you adopt a strict ethics of care and “do no harm” approach, you may need to develop a balancing test that you like. Polonetsky and colleagues have their risk-assessment approach;[23] above we mentioned the UC Berkeley Library’s guidelines.

- Some benefits may not be computable, but efforts to measure value can nevertheless produce useful insights, and the same holds true with big data projects.

Oversight and advocacy

Implementing any of these strategies requires oversight and advocacy in varying degrees. For instance, regulations might need to be changed, or the policies of review boards revised to adopt definitions for terms such as privacy, confidentiality, security, and sensitivity.

As part of the Building LLTDM Institute, we can’t necessarily achieve either regulatory change or change to review boards on the spot, but you can bring strategies back to our institutions if you wish to pursue them.

What we can also do as part of this institute is begin considering the development of guidance on research community norms and best practices.

- Suomela, T., Chee, F., Berendt, B., & Rockwell, G. (2019). Applying an Ethics of Care to Internet Research: Gamergate and Digital Humanities. Digital Studies/le Champ Numérique, 9(1), 4. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/dscn.302 ↵

- Effy Vayena et al., Elements of a New Ethical Framework for Big Data Research, 72 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. Online 420 (2016), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr-online/vol72/iss3/5 ↵

- Please Rob Me. (2010). https://pleaserobme.com/ ↵

- Christen, K. (2018). Relationships, Not Records: Digital Heritage and the Ethics of Sharing Indigenous Knowledge Online. In The Routledge Companion to Media Studies and Digital Humanities (1st Edition, pp. 403–412). Routledge. https://www.kimchristen.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/41christenKimberly.pdf ↵

- See the WIPO policy subject area of Traditional Knowledge (TK), which is “a living body of knowledge passed on from generation to generation within a community. It often forms part of a people’s cultural and spiritual identity. WIPO's program on TK also addresses traditional cultural expressions (TCEs) and genetic resources (GRs).” https://www.wipo.int/tk/en/ ↵

- Okediji, Ruth, Does Intellectual Property Need Human Rights? (June 25, 2018). New York University Journal of International Law and Politics (JILP), Vol. 50, No. 1, 2018, Harvard Public Law Working Paper No. 18-46, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3202478 ↵

- “By submitting, posting or displaying Content on or through the Services, you grant us a worldwide, non-exclusive, royalty-free license (with the right to sublicense) to use, copy, reproduce, process, adapt, modify, publish, transmit, display and distribute such Content in any and all media or distribution methods now known or later developed (for clarity, these rights include, for example, curating, transforming, and translating). This license authorizes us to make your Content available to the rest of the world and to let others do the same. You agree that this license includes the right for Twitter to provide, promote, and improve the Services and to make Content submitted to or through the Services available to other companies, organizations or individuals for the syndication, broadcast, distribution, Retweet, promotion or publication of such Content on other media and services, subject to our terms and conditions for such Content use.” Twitter Terms of Service. (n.d.). https://twitter.com/en/tos ↵

- Kate Crawford & Jason Schultz, Big Data and Due Process: Toward a Framework to Redress Predictive Privacy Harms, 55 B.C.L. Rev. 93 (2014), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol55/iss1/4 ↵

- Wikipedia editors. (n.d.). Common Rule. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Common_Rule ↵

- National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. (1979). Belmont Report: Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/index.html ↵

- Webb, H., Jirotka, M., Stahl, B.C., Housley, W., Edwards, A., Williams, M. L., Procter, R., Rana, O. F., & Burnap, P. (2017). The Ethical Challenges of Publishing Twitter Data for Research Dissemination. WebSci ‘17: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Web Science Conference, 339–348. https://doi.org/10.1145/3091478.3091489 ↵

- Christen, K. (2018). Relationships, Not Records: Digital Heritage and the Ethics of Sharing Indigenous Knowledge Online. In The Routledge Companion to Media Studies and Digital Humanities (1st Edition, pp. 403–412). Routledge. https://www.kimchristen.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/41christenKimberly.pdf ↵

- See Lor, P.J., & Britz, J.J (2012). An Ethical Perspective on Political-Economic Issues on the Long-Term Preservation of Digital Heritage. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 63(11), 2153–2164. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22725 and Hursthouse, R., Pettigrove, G., & Zalta, E. N. (Ed.) (Winter 2018 Edition). Virtue Ethics. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2018/entries/ethics-virtue/ ↵

- Leonelli, S. (2016). Locating ethics in data science: responsibility and accountability in global and distributed knowledge production systems. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical & Engineering Sciences, 374(2083), 1–12. ↵

- Suomela, et al note, "Unlike previous ethical theories that start from the position of an independent rational subject thinking about how to treat other equally independent rational subjects, the Ethics of Care starts with the real experience of being embedded in relationships with uneven power relations." Suomela, T., Chee, F., Berendt, B., & Rockwell, G. (2019). Applying an Ethics of Care to Internet Research: Gamergate and Digital Humanities. Digital Studies/le Champ Numérique, 9(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.16995/dscn.302. ↵

- Dixon, S., & Quirke, L. (2017). What’s the Harm? The Coverage of Ethics and Harm Avoidance in Research Methods Textbooks. Teaching Sociology, 46(1), 12–24. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0092055X17711230 ↵

- Vayena, E., Gasser, U., Wood, A., O’Brien, D. R., & Altman, M. (2016). Elements of a New Ethical Framework for Big Data Research. Washington and Lee Law Review Online, 72(3), 420–441. https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr-online/vol72/iss3/5 ↵

- Polonetsky, J., Tene, O., & Jerome, J. (2014). Benefit-Risk Analysis for Big Data Projects. Future of Privacy Forum. https://dataanalytics.report/Resources/Whitepapers/aa942e84-9174-4dbe-b4cc-911bff14daf8_FPF_DataBenefitAnalysis_FINAL.pdf ↵

- Webb, H., Jirotka, M., Stahl, B.C., Housley, W., Edwards, A., Williams, M. L., Procter, R., Rana, O. F., & Burnap, P. (2017). The Ethical Challenges of Publishing Twitter Data for Research Dissemination. WebSci ‘17: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM on Web Science Conference, 339–348. https://doi.org/10.1145/3091478.3091489 ↵

- https://www.lib.berkeley.edu/about/digital-lifecycle-program-steering-committee ↵

- Suomela, T., Chee, F., Berendt, B., & Rockwell, G. (2019). Applying an Ethics of Care to Internet Research: Gamergate and Digital Humanities. Digital Studies/le Champ Numérique, 9(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.16995/dscn.302 ↵

- UC Berkeley Library. (2020). Ethics Local Practices for Digitization of and Online Access to Collections Materials. https://docs.google.com/document/d/10Ux--7GgrOvoYzTAlbTRtdVAbENYRsCr9HmUNGw9LC4/edit?usp=sharing ↵

- Polonetsky, J., Tene, O., & Jerome, J. (2014). Benefit-Risk Analysis for Big Data Projects. Future of Privacy Forum. https://dataanalytics.report/Resources/Whitepapers/aa942e84-9174-4dbe-b4cc-911bff14daf8_FPF_DataBenefitAnalysis_FINAL.pdf ↵