9 Short instructional sessions

Rachael Samberg and Timothy Vollmer

Not everyone has either the time or the need to host a four-day, intensive extravaganza to teach LLTDM. In this chapter, we present modular opportunities with examples of shorter sessions tailored for different audience needs.

Quick overviews (15-minute sessions)

Why and when?

There are a number of contexts in which a 15-minute overview of LLTDM can be the perfect vehicle by which to introduce core concepts to new audiences. Short overviews work best for attendees who don’t need to become experts in the literacies, but wish to (or should!) be aware that the issues exist. As such, we have taught these quick overviews for:

- Students who have been assigned their first TDM projects

- Scholars interested in creating digital research archives

- Librarians who wish to feel more confident advising users about TDM projects

What should you cover?

The main goals of a 15-minute session are simply to help attendees begin to “issue spot,” and learn more about whom to contact if they get stuck or have questions. We typically approach 15-minute sessions as a quick lecture. (Fifteen minutes of an introductory overview of all the literacies just isn’t conducive to incorporating an exercise. An exercise is far more feasible if you focus on just one of the literacies.) And note that there is some false advertising here, as these sessions have always run 18-20 minutes despite being billed as 15. We just can’t lay enough context for the above takeaway points in only 15 minutes!

We believe the core concepts to establish and instill in a 15-minute session include:

- Copyright: It’s typically fair use to download or compile copyright-protected content provided you don’t break digital locks (DRM), but there are limits on what you can republish or share from what you download or compile. You don’t need to worry about fair use and how much you republish at all, though, if you use public domain materials or just facts/ideas.

- Contracts: Even if a use is fair under copyright, or if the content is not protected by copyright, there may be a contract that restricts scraping and TDM. Look for fair use savings clauses in applicable license agreements or website terms of use/terms of service. If you’re using a library database to download, what matters is the library’s license agreement, not the database’s generic terms of use online. Finally, consider vendor- or publisher-authorized options like APIs or simply negotiating with the vendor/publisher for what you want.

- Privacy: Mining data could violate federal or state privacy laws, but there are important legal exceptions that support TDM research. For instance, state privacy laws (1) often have exceptions for research that is “newsworthy” or of sufficient “public interest,” (2) typically don’t protect deceased people, and (3) are inapplicable if the subject of the works cannot be identified. You can consider the applicability of those exceptions or alternatively seek consent from the subjects of the works you’re using. Collecting voluntarily-released data from the subject (e.g. a person’s public Tweets) does not violate privacy rights, but may present ethical questions.

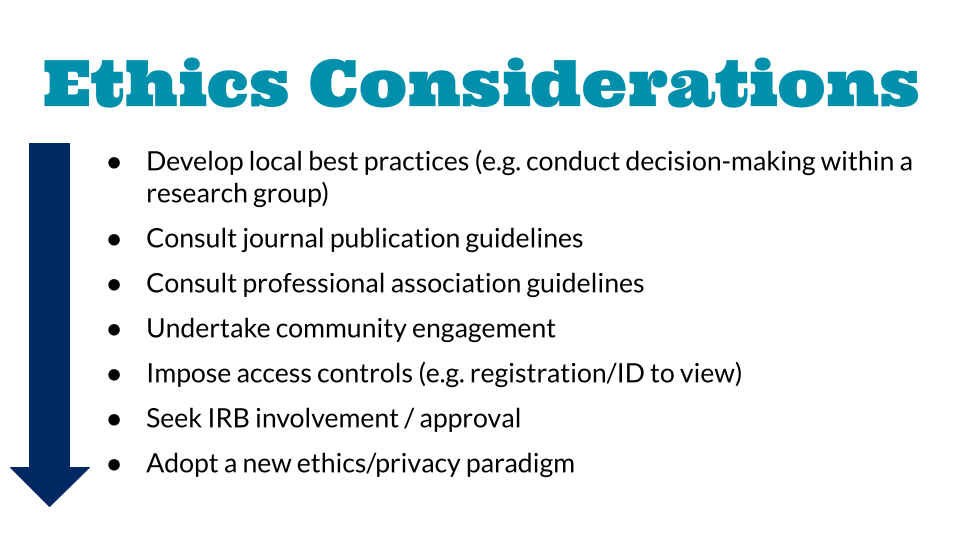

- Ethics: To address ethical concerns, there’s a continuum of actions you could consider with increasing degrees of commitment required. Here’s a quick example of that spectrum:

What it looks like

You can check out some of our 15-minute overviews here:

What to know about law and ethics when archiving and mining data…in just 15 minutes! [Video] [Slides + Speaker Notes]

Legal literacies for text data mining [Slides + Speaker Notes]

One-shot deep(er) dives (1.5-hour sessions)

If you’ve got about 1.5 hours for a “one shot” workshop (lecture + exercises), participants can come away with practical, working knowledge of how to implement the literacies for their own projects.

We’ve successfully run such sessions relying on 45 minutes of lecture plus 15 minutes of questions, followed by a 30-minute exercise—giving participants essential hands-on experience with putting their newly-acquired knowledge to the test.

Why and when?

One-shot workshops are well-suited for graduate students and professional staff who are at the planning stages of or are deeply engaged in supporting TDM research. Catching the interest of scholars before they begin their work can be challenging, but building relationships with digital scholarship centers or labs as well as digital humanities faculty can be essential for bringing attention to the trainings, or even integrating the sessions into required coursework.

What should you cover?

We recommend including all of the takeaways we identified above in the 15-minute sessions. But we also believe it’s helpful to provide the following additional context, requiring around 8-10 minutes per topic:

Background

- Foreground that you’re helping people understand what they can do, not telling them that they can’t or shouldn’t conduct the research

- Use real-world examples from your practice or scholarly case studies to highlight how many TDM projects intersect with copyright, licensing, privacy, and ethics.

- In a live session, try to get a sense of the TDM projects with which participants are involved so you can tailor examples as you go to issues arising in participants’ own research

Copyright

-

- Copyright law grants exclusive rights to original expression for limited periods of time

- These exclusive rights include reproduction, distribution, display, creation of derivative works, and performance

- During the protected period of time (currently author’s life + 70 years), the author holds these rights exclusively

- There are exceptions to these exclusive rights that are critical for research and scholarship, and one such exception is fair use

- Courts have determined that conducting TDM is a fair use, and therefore not a copyright infringement.

- But that doesn’t mean someone can republish the entire copyright-protected corpus they created. While TDM is fair use, republishing the corpus may not be.

Contracts

-

- Regardless of whether TDM is fair use, or even if the content you’re scraping and analyzing is in the public domain and not protected by copyright at all, there might be other agreements that restrict what you can do with the materials. In other words: Just because TDM is permissible under copyright law doesn’t necessarily mean you’re free to download, create, and circulate a TDM corpus.

- This is because there may be a variety of different contracts that supersede what’s allowed under copyright law.

- When you’re working with social media or other websites to conduct TDM, you might want to be able to download a large portion of it, or maybe even everything on the site. It’s important to understand that doing so could violate the website’s terms. The website’s Terms of Use are considered “browse wrap” agreements, meaning you consent to the terms simply by browsing, or viewing, the site.

- But it’s also important to note that these kinds of browse wrap agreements are not always enforceable by a court. Contract issues are questions of an individual state’s law, rather than federal law like copyright. Courts in different states may require that users have either actual or constructive notice of the terms of use. This basically means: Should a reasonable person have been aware of the terms based on how the website was presented? Courts that are evaluating whether constructive notice was provided will look to factors like how visible the terms of service were, and whether the users were asked to consent to them. Some courts have simply ruled that browse wrap agreements are indeed enforceable.

- So what should you know as a general guideline? You should be aware that these terms may exist, and you should make risk calculations accordingly. Often, if you are accessing publicly-available content and downloading it just to scrape—without breaking access barriers to get at the content—then it could potentially be a low risk to violate the terms because it may be hard for the content owner to prove damages.

- Researchers might also be interested in scraping journal, newspaper, and content databases that are offered by research libraries. When libraries subscribe to these databases, we sign contracts with publishers. If you are accessing material from library databases, then our database agreement applies to you, even if you didn’t sign anything yourself.

- Database licenses can affect researchers’ ability to make TDM uses of the material—whether with respect to access by limiting researchers’ right to make downloads, or republishing via restricting circulation of the content.

- It may be possible to skirt contractual restrictions by using a publisher’s application programming interface (API) or negotiating with the publisher to secure the necessary permission.

Privacy

-

- There are both federal and state privacy laws that can govern the collection and dissemination of content for TDM research. Often, institutional research boards address federal law applicability since those are more relevant within the context of human subjects research.

- State privacy laws typically cover what we commonly think of as intrusion and invasion. It’s helpful to understand those laws, but perhaps equally helpful to be aware of pertinent exceptions:

- The right of privacy is not violated by disclosures of matters of legitimate public interest.

- Specifically with respect to public disclosure of private facts, courts also have to balance a person’s right to keep information private with your First Amendment right to disseminate information to the public. In achieving this balance, courts sometimes look to whether the facts you’re seeking to disclose are of legitimate public concern and/or would be highly offensive to a reasonable person.

- When a person dies they lose the common law right of privacy, though not necessarily their commercial right of publicity as to their name or likeness—that depends on state statute. However, you’re likely not doing your research for commercial gain anyway, so for all intents and purposes, if you’re mining and disclosing information that would typically be protected by state (as opposed to federal) laws, the state laws usually no longer apply if the subject is deceased.

- There are no privacy concerns if the people are not identifiable from the information you release.

- If someone has disclosed the information themselves—such as by posting the content voluntarily on social media sites—or given you permission, they cannot sustain a privacy tort claim.

Ethics

-

- There are often questions of ethics that do not fall under privacy, copyright or contract law, but that researchers may still want to consider in their research. This includes information that would be considered “private” under law, but which we (as individuals) may consider to be sensitive in some way.

- What’s unique about ethical concerns in TDM research is that we are bringing together a vast amount of data, in many cases decontextualizing that content from its original source, and making that data available for mining. This can subject individuals to harm, allow for the targeting of disadvantaged communities, or exploit indigineous knowledge, among other risks. In other instances, collecting and mining data may expose cultural heritage sites to looting, or reveal the location of endangered species and subject them to poaching or exploitation. Again, these issues may be present in other types of research; but with TDM, we’re looking at exposure at scale.

- Ethical questions for TDM research can be challenging because there are no legal answers, and TDM researchers are only beginning to grapple with ethical considerations.

- So, how do we approach these questions? There’s a continuum of actions one could consider with increasing degrees of commitment, which we’ve excerpted visually above. Researchers may also wish to consider the long-term relationships they hope to build with different communities that they are working with or studying. For now, researchers have to create our own ethical guidelines and seek out guidance from similar projects, professional organizations, publishers, and others.

30-minute exercise

-

- In our experience, the real learning in the 1.5-hour workshop comes through the exercise at the end. We recommend dividing participants into groups of 2-4 so that they can talk through the questions together for about 15 minutes before rejoining a plenary discussion. If you’re teaching online, having two instructors is helpful so that you can pop in-and-out of breakout rooms.

- We have found that the groups working on their own can apply basic issue-spotting skills—but when the instructors call everyone back for a plenary discussion of the questions, participants are amazed to discover the many nuances they may have elided. We provide some suggested exercises in our participant packet for the four-day institute. There’s no reason these exercises can’t be repurposed for 1.5-hour workshops!

What it looks like

Text Data Mining & Publishing [Slides + Speaker Notes] [Exercise]