PART 2: USING CATEGORIES TO ORGANIZE

In previous lessons we talked about “categories” without defining them exactly because that concept is familiar to you. But to become a master organizer you need to be more precise in how you think about categories.

A “Category” is a set or group of resources in which the members are treated the same — EQUIVALENT — for some purposes. “Equivalent” doesn’t mean that all the members are exactly the same, only that their differences aren’t important for some purpose. For example, all the books in the category “sports books” are about sports, but of course they are different books.

Categories are defined in different ways depending on the type of resources you are organizing and the reasons for organizing them.

For example, the “kid” category that we talked about on the first page of this book can be defined in at least three different ways.

1) The simplest way to define the “kid” category is by using an age test. “Kid” and “child” are pretty close in their meanings. Governments usually have legal definitions of the “child” category as a person who is younger than some specified age, usually 18. So we could use the test “is the person younger than 18?” to decide if someone was a kid.

2) But this single age test doesn’t capture the idea that very young children are not called kids. A “newborn” is less than a few months old, a “toddler” is between 1 and 3 years old, and a “baby” could be either a newborn or a toddler. An older child between 13 and 17 is often called a “teenager.” These other categories suggest that we need to use two age tests to define the “kid” category:

-

- Is the person older than 3?

- Is the person younger than 13?

3) A third way to define “kid” doesn’t use age tests at all. Someone might scold a child by saying “stop acting like a kid” because they are being immature or not responsible. When they say that, they are defining “kid” using some idea of how similar the child is to some ideal child who is always mature and responsible. Many of the most familiar categories are defined using principles of similarity like this.

This example of the “kid” category motivates two powerful concepts that master organizers use to analyze and design a system of categories. These are CATEGORY STRUCTURE and CATEGORY CONTEXT.

CATEGORY STRUCTURE

We organize resources when we put them into categories. But in addition to thinking about the types of resources that we put into categories, it is useful to think about the principles or rules that we use when we define a category. We just showed how the “kid” category could be defined using one or more age tests or using similarity.

The way in which a category is defined is called the “category structure” and In the following chapters we will compare different kinds of category structures:

- Categories defined by a list of their members

- Categories defined by single properties

- Categories defined by more than one property

- Categories defined by similarity

- Categories defined by shared goals or activities

Category structure determines:

- how you tell whether something belongs in the category

- how similar the category members are to each other

CATEGORY CONTEXT

We can distinguish three contexts or situations in which categories are created:

- The INDIVIDUAL or PERSONAL context, when one person organizes possessions, activities, or interactions for their own purposes. This is the situation when you organize your own books, toys, clothes, or things you want to do.

- In the SOCIAL or CULTURAL context, where groups of people interact together over time to create categories in their language and culture (“kid” is a cultural category).

- In the INSTITUTIONAL context, where a company or government or other formally organized group defines categories in business practices, laws, regulations, or standards. For example, “child” is an institutional category when a government specifies an age test. Other examples are when school systems organize their students into schools, grades, or class categories.

SOCIAL and CULTURAL categories are often the starting point for categories in the other contexts

- These types of categories emerge whenever people interact in groups and there are thousands of them in every language

- For example, every culture and language has a concept of “friend” as someone you enjoy doing things with

- As an individual, you have different categories of friends. You have family friends, school friends, sports friends. All of these categories are based on the cultural category of friend

- INSTITUTIONAL categories are often created to make cultural categories precise or standardized. This enables them to be used in business, science, or to control behavior.

COMPARING CULTURAL AND INSTITUTIONAL CATEGORIES FOR COLOR

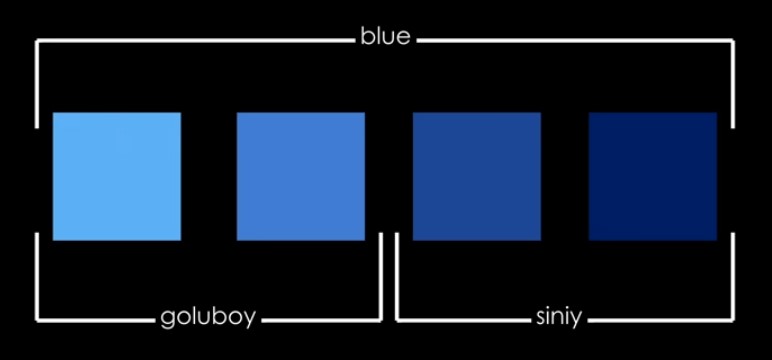

Every language has concepts and words for different colors. Cultures often associate concepts with colors – red is a “warm” color and blue is “cold” for most people. But languages differ in how they “carve” colors from the visible spectrum. For example, the Russian language has two words that distinguish light blue colors (“goluboy”) from dark blue colors (“siniy”), but English only has “blue.”

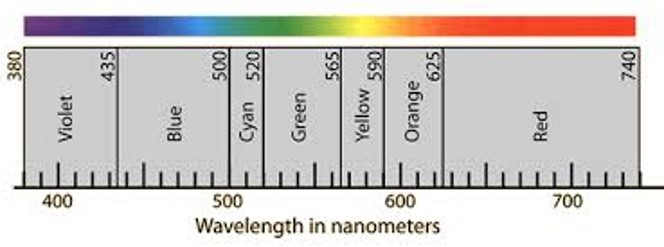

Scientists define color boundaries using the wavelength of visible light.

The printing, painting, and the graphic design industries have developed color standards to make sure that a color looks as it was intended. For example, in the Pantone system, every color has a unique identifier. This enables a company or product to specify a “brand color” no matter where it appears or how it was produced. For example, the familiar yellow color used by McDonald’s is the Pantone color PMS 123 C.

Here are some other Pantone colors: