Autonomous entities ◆ competitive multiplicities ◆ layering ◆ alternating contexts

Key terms and concepts introduced in this chapter:

- autonomous entities

- competitive multiplicities

- context-to-Tom distance

- layers and layering

- alternating contexts (spatial and temporal)

- pluralities

Key terms and concepts mentioned in this chapter that should now be familiar:

- attractors

- cultural contexts

- ethical values

- narrative figures

- ToM

- worldviews

16.1. Arrays of cultural contexts

Imagine that I have one sister and she is sitting in front of me and making a suggestion as to what I should do. If, alternatively, that I have six sisters and they are all in the same room with me and all talking at once and all making different suggestions. Well, that is an entirely different situation. Finally, if I have six sisters but they live in different parts of the world and I visit them one at a time, that is a still different situation. The advice of my sister or sisters has a different impact on me based on these various situations. This chapter organizes this variety into four common configurations and calls them “arrays.”

Part of determining exactly how we should characterize a credible relationship of our constructed *ToM to a *cultural context is determining how that *context fits among all the other *contexts we consider are (or ultimately conclude to be) relevant to the *ToM.

First, understanding a *cultural context’s place among other *cultural contexts helps us decide “*context-to-ToM distance.” This “*distance” is not an indication of the degree of acceptance of a *cultural context, because a *ToM might be in a posture of resistance or acceptance of a *worldview or *value which is part of the *context. This is instead a “strength” factor. (*Status is the term we use to describe a *ToM’s relationship to a worldview or value on the acceptance-rejection spectrum.)

Second, keeping in mind how a *cultural context fits among other *contexts facilitates the broad and successful gathering of *contexts that need to be considered because, I will argue in this chapter, contexts can not only be present in their obvious multiplicity (side-by-side so to speak) but might be absent-present sequentially. Thus, we should look beyond the present moment of our *instance to consider whether there are relevant contexts from the past or “just around the corner” influencing the current moment. Further, it is definitely the case that *cultural contexts can be present, even powerfully present, as a hidden component of another *context or “behind” (*layered behind) another context. In other words, we cannot just stop our gathering when we find what is obviously before us but must take time to consider the possibilities of arrays of sequentially present *contexts, or *layers of *contexts.

Third, understanding arrays affords complexity and realism to the constructed *ToM. In the real world we juggle *contexts all the time and our mind pays attention to some more than others, switches back-and-forth among them, measures them against one another, and so on. In truth, when we are determining arrays of *cultural contexts, we are not just acknowledging empirical arrays (an example of the first array described below, “*autonomous entities,” might be: grandmother is in the living room, my father is in the kitchen, my partner is back at home waiting for me) but also how they are represented in my mind. Karen was offered as an example not only because of the way her case dramatically represents autonomy among various entities but more specifically because these are mental entities. I suggest that our cultural influences can be similar in their autonomous and contradictory presence in our mind—except that grandmother can actually become sour if I do not accept her view of things and I must actually deal with it, and so on. Thinking of cultural contexts as arrayed in different ways helps us accept and explore the contradictions of a *narrative figure’s thoughts, feelings, and actions—something we are quite used to in the real world. *Narrative figures tend to be not as complex, but they can be, and thinking in terms of possible *cultural contexts anyway creates complexities which might not otherwise be there if we were just consuming the *narrative “naturally” without constant analytic interventions.

Having previously made an argument for the importance of *pluralities and why we should embrace them, I would like to now offer my view of the types of plurality arrays we encounter as we gather *cultural contexts while asking the litmus test question of which might in fact be participating in the formation of a person’s thoughts, feelings, and actions. Our analytic focus is, after all, on the composition and influential power of the cultural contexts.

While the below list might seem simply to be based on a mathematical shuffling of the most probable ways that entities relate to one another, in fact they have more organic origins in psychology, neurobiology, narratology, and religious ideology.

I will outline four basic arrays of *pluralities. Please keep these in mind when you are using the *course method because I believe it might help untangle some of the confusions that will arise, as well as help determine the best direction of your analysis.

16.2. Autonomous entities

Autonomous entities can refer either to *cultural contexts or to *ToM. I would like to make two different points.

First, *autonomous entities as *cultural contexts are extremely common. Pressure to have nationalist pride, on the one hand, but, on the other, to behave with humility in your social relationships is an example. These two cultural pressures are separate from one another, with separate origins and separate imperatives. They do not coordinate, nor can they be reconciled meaningfully. Yes, you could create a bridging concept. You could argue, for example, that “the culture in question seems to value hierarchies and when at the top of the hierarchy one can or is encouraged to express pride and when at the bottom one must take care and express humility.” That solves the problem logically but does not seem like a good representation of what is really happening in actual situations. Instead, it seems, members of this imagined culture probably simply pay little attention to the contradiction of embracing both and unless a specific situation forces them to, will not make an attempt to reconcile them. In this way, the concepts are autonomous: they do not need one another in order to fully exist and are probably not acting in a coordinated way together. The concept of *autonomous entities frees us from needing to explain the many contradictions of a culture and allows us to ponder many contexts without feeling required to prioritize them. They are autonomous and come into play, well, when they come into play.

Second, in the manner of Karen Overhill, it is better to think of *ToM as complicated, rather than one rational, coordinated, organically whole entity. “On most days I’m a Buddhist but when I am around my Christian friends I notice that I am thinking pretty much like them.” This is an example of multiple *ToM, where the subject is self-aware of the multiplicity. But more common is perhaps blindness to one’s autonomous parts. It is not hard to imagine someone who has power harassed an individual to later, in some discussion, make the comment, “I respect her.” Or, as another example, one might behave differently around one’s parents and one’s friends but not really notice the difference until someone points it out. So, the concept of autonomous entities allows us to build a more complex *ToM, one that has fractures in it. The *ToM is in pieces, with these pieces not logically fitting well together but when articulated in their full, contradictory complexity approach being a very good description or explanation of a person’s thoughts and behaviors. Obviously, this is not an invitation just to make a shopping list of all of manner of behaviors and avoid the hard work of seeking some larger principles that can explain some or also of them at a meta-level. But, again, it is a question of balance. It just seems reasonable to not expect someone to be a logical, coordinated whole with one set of logical ethical values.

16.3. Competitive multiplicities

I want to steal a cookie. It is there on a plate. The person has left the room. There are others nearby but they are not looking at me. If I steal the cookie the person, upon return, will not know who took it. …

So, I’m thinking a lot of different things:

- “It is wrong to steal”—an ethical value.

- “It is not so very wrong to steal when it is a cookie”—an ethical value (ethical principles should be applied proportionately and with flexibility, not as absolutes).

- “I really want the cookie.” (Hmm, I am not sure there is an ethical value here. I guess we could said the “right to pursue happiness,” a hedonist argument. But I think this is better thought of as a low-order, corporal desire that impels action.)

- “I won’t get caught.” This is where situation meets culture. We will encounter this over and over.

- “Most people would steal the cookie so it is okay for me to steal, too”—common practice argument, again pushing aside ethical principles.

I steal the cookie.

The situation is such that the cultural contexts (*values) that tell me I should not are pushed aside by the immediacy of the situation. That does not present an analytic difficulty for us in this course because we are not trying to prove that ethical values result in actions. We will only be arguing to whether or not the value passed through the mind, and what is its *status.

This last reason above might be an operative principle (follow *common practices) but it is not an ethical one. Ah, but it could be! If you are in a group (and you probably are) that presses you to do things as the group does them, then there is something of an ethical principle involved: follow group practices to reinforce the stability of the group / honor the groupness of the group.

*Competitive multiplicities arise in situations such as the above when there are many sources of contexts (these might be internalized *values or external entities such as different friends, or one’s parents and one’s friends suggesting or explaining things differently)—and there usually are—which are competing for different results in the same *instance, about the same thought, action, or feeling. That an individual selects Choice B instead of Choice A does not prove that there never was present the *value associated with Choice A. It just did not win the day. However, next time around Choice A might be the result. If that is the case, then we might be able to say this person is split between these two *ethical values, takes both seriously, and may choose one or the other, depending on the situation. One can embrace the Buddhist moral imperative of non-violence / no-killing yet still take the spider outside in a jar on one day and just smash it on another day.

Narratives frequently use *competitive multiplicities to explore internal and interpersonal conflict. Narratives that invite us to ask while we read (or view) “What would I do?” are giving us a chance to think about the *competitive multiplicities in our own lives. (“Should I be a good son or daughter and spend some extra time with my parents? Or, should I be a good student and stay on campus to study for the final? Or, should I be a good friend and listen again tonight to the romantic troubles of my roommate?”) Competing ethical choices can be the result of contradictory ethical principles. More commonly in our films *values are in competition with *common practices and situational factors.

16.4. Layers and layering

Ariwara Narihira, we surmise from the many poems left by him and comments about him scattered across early Japanese texts, was a man who was easily caught in the thralls of love. Elegant, sensitive, handsome, deeply moved by women, he is a 9th-century icon of a man whose heart led his actions. Of the women he loved there was one (at least) he should not have loved, a woman of higher status who then was called into service by the emperor for his private pleasures. At his command she relocated to the palace. As the story is told, Narihira, heart-broken, visited her now empty bedchamber, laid down in the moonlight, and wrote a poem that has puzzled Japanese literary historians for more than 1,000 years.

There are many ways to translate the 10th-century Japanese that we find in The Tale of Ise, Episode 4, which describes this love affair. Here is one:

Long ago, a lady was living in the western wing of the residence of Her Majesty the Empress Mother on the eastern side of the Fifth Avenue. In spite of himself, the man could not help but fall deeply in love with this lady and began to frequent her apartments. However, around the tenth day of the New Year, she suddenly vanished. The man discovered where she was, but it was not a place where ordinary people could go, so he was deeply unhappy.

At the beginning of spring in the following year, when the plum blossoms were at their peak, the man’s heart was filled with poignant memories of the year that had passed, and he returned to the lady’s former apartments. He gazed intently at his surroundings, now standing, now sitting down, but nothing looked as it had the year before. Bursting into tears, he lay down on the bare floorboards and remained there until the moon sank low in the sky.

Recalling the events of the previous year, he composed a poem:

Could that be the same moon?

Could this be the spring of old?

Only I am as I have always been,

but without you here

….…….

Then, in the faint light of dawn, he returned home, weeping bitterly.[1]

Here are two other versions of the poem, translated by me while making no effort to “fix” the opaque quality of the original:

Is this not the moon?

Is this not spring as spring always is?

One “me,”

the “me” as before …

and,

Ah, this moon!

Ah, this spring is not past springs!

One “me,”

the “me” as before …

The first takes the grammar of the first two lines to be rhetorical questions. The second treats the same two lines as exclamations. I am not offering this as a puzzle in interpretation, rather just the opposite. Even with very different treatments of the grammar the *layering is the same: “I have come back to ‘our’ place and though inside ‘me’ our love continues as before, things have indeed changed and you are not here …” This is a *layering of time: “time” inside me is still living our relationship but ‘real time” has progressed and taken you from me, and I feel that gap, and it makes me cry. Memories play a huge role in love narratives, so much so that at times it seems like the painful memory of love is the only authentic expression of being in love. But I would like us to handle memories more complexly when possible. There is “living in the past” where one is lost in a memory and temporarily (or radically) disconnected from the present. This is familiar to us because it is a common mental state. But there is also “past-in-the-present”: we are in the present moment but a past moment is profoundly affecting it. This is of course at the core of perception itself and it is also where *attractors are active. But, as a narrative technique, it sometimes has a more prominent role.

The Hong Kong film 2046 (2046, 2004) is the third film in a trilogy that follows several narrative figures across long stretches of time and place while constantly inviting the viewer to consider all these different times and locations when trying to understand the present moment thoughts of feelings of its characters. One example of this is the unfortunate woman Mimi of the first film in the trilogy—Days of Being Wild (Afei zhengzhuan, 1990, Hong Kong). She returns in 2046 as two characters, a woman named Lulu and a nameless android. Mimi was passionately in love with the central figure of the first film, Yuddy (“York” in some subtitles). In the third film Yuddy’s essential characteristics and problems of love find a new home in Chow Mo-wan (who makes a puzzling cameo appearance at the end of Days of Being Wild, which was completed, by the way, fourteen years before 2046). This Chow meets Lulu, whom he “remembers” as Mimi, although she will not confirm his memory for him. Lulu is murdered early in 2046 and continues her presence in the film as an android. Through the *layering of times and identities, Mimi-Lulu-Android becomes less a narrative character than an idea: what it is like to devote one’s life to love when one tends to love bad partners and does not protect oneself in them. It is this layered history that gives the scenes their poignancy.

- Mimi-Lulu’s smile in the Chinese film 2046 (2004), Clip 1:

- Mimi-Lulu’s smile in the Chinese film 2046 (2004), Clip 2:

This “idea of a person” supports effectively one of the assertions of 2046, namely, “All memories are traces of tears.” But, at a higher level, it is brilliantly supporting a more powerful theme of 2046, that we do not just love a person, we love a “someone + all the memories of other lovers that this person calls forth” entity.

*Layering in 2046, then, blurs the distinction between the boundaries of identities. It turns out that this is more common in East Asian love narratives than one would expect, given the Western emphasis on “soulmates” (two distinct entities who are a perfect match for one another).

In early Japan, there was a woman named Izumi Shikibu who was known for her passionate poetry, exceptional rhetorical skills, and many love affairs, some of them scandalous because she was a commoner and her lovers were royalty, and married. Although it is told in third person, it seems Izumi Shikibu wrote a memoir (The Story of Izumi Shikibu, ca. 1007?) of her love affair with one of these princes. The story is about the first ten months of the relationship with older brother of her former lover, who died while still in his twenties. At the first anniversary of the death of his younger brother, Sochinomiya, the older brother, makes an offer of romance to Izumi. He sends a branch of orange blossoms, known as flowers that bring back memories, to indicate that he realizes Izumi must be sad at this time of year. This expression of sympathy is also an invitation for love. She responds to his flower branch with a poem, expressing her vulnerable longing for being able to once again talk to her dead lover:

rather than cloaking me

in the sweet nostalgia

of this fragrance

—little warbler—

how much sweeter

to hear again

that song

and he responds strategically:

wing to wing

the little warblers

sang in turn—

how could someone not know?

my voice

is now and ever

his match[2]

In other words, his argument for why he should love her as she loved his younger brother rests on bloodline similarity: we are of the same family “tree” since both sat wing-to-wing on the same “branch” and I “sing” just as well as him. The American in me says, “No, you don’t get to claim a woman just because you are a brother” but the Japanese premodern scholar reminds me, “It was the day’s custom for an older sibling to take responsibility for a wife were she to be widowed unexpectedly” and “Family-to-family alliance, status, and security, are all stronger reasons for romantic bonding than ‘chemistry’ or individual feelings of love.” The *layering here is: “Older brother, younger brother, what’s the difference? Let’s not worry about the details. They are both princes, and related as full blood brothers.” *Layering in East Asian love narratives often challenges our Western high valuation on individual-to-individual love as the fundamental structure of “true” love.

Narihira’s poem about the moon, Mimi-Lulu of 2046, and the older brother = younger brother love offer to Izumi are examples of *layering that engage “past-in-the-present” moments and/or blur identities. As noted, these are very common in love narratives. Memories (or anticipation, which is essentially a “future-in-the-present” moment) and entity associations (person A is like person B) generate complex identities and slippery narratives. Perhaps this is the place to also note that secrets are another common love narrative technique to *layer identities. A powerful example of this is the South Korean film Shiri (Swiri, 1999) where a North Korea spy and a South Korea spy fall in love, not knowing the “true” identities of each other. In the climax of the film, the spy from North Korea, Myung-hyun (the name her lover knows) / Bang-hee (her government agent name), is attempting to kill South Korean government officials that her lover is tasked with protecting. The two face off, gun-to-gun, and their *layered identities as lovers and government agents clash:

The climax scene from the Korean film Shiri (1999)

We will discuss later the major role that secrets often play in *love narratives.

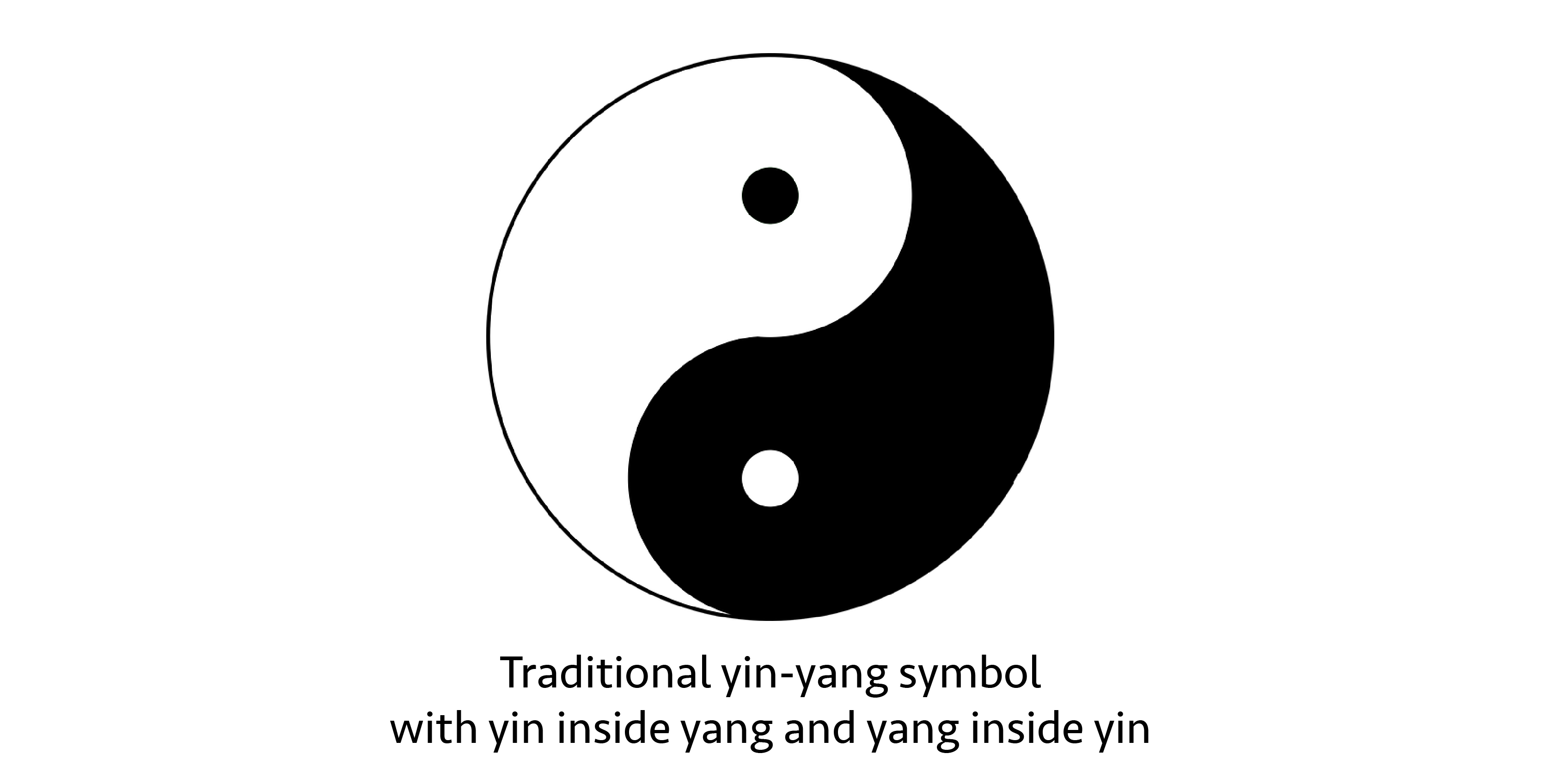

There is another important type of *layering that we must consider: hidden entities that are nevertheless powerful. The essential principle of ancient Chinese cosmology—that there is always yin inside yang and always yang inside yin—is represented with the symbol:

The Book of Changes (Yijing), portions of which are very, very old (11th-5th century BCE), is built on the principle of ever-changing states with the seeds of the upcoming state hidden within the current state. Only two of the sixty-four hexagrams around which the Book of Changes takes as the fundamental states of things are “pure.” All others include some aspect of yin or some aspect of yang. Further, the Book of Changes is built on the assumption that the true model of change is that the upcoming state pre-exists as a seed inside the current state. Thus, to be attentive to the occulted, hidden, and secret next-state gives one an advantage in understanding the current situation and what best actions should be taken. Put in the language of *layering, the occult is *layered behind the visible; it is invisible but very powerful.

This very old way of thinking, I would argue, underlies measurements of wisdom and sensitivity we can see in East Asian narratives: those who only notice the obvious or think that the obvious as the most important thing to attend to do not understand how the world works (the *worldview represented by ancient Chinese cosmology adopted by Daoism). This high value placed on the occult, I would argue, “spills over” into a high tolerance for layeredness (especially in the form of memories, complicated labyrinth-like timelines, blurred identities, multiple identities, and secrets) in narratives in all of its varieties. Thus, going back to the young brother / older brother duo, the “hidden” connector of bloodline actually had a strong claim to authenticity for readers of the day. It helped make the new relationship feel “natural.” Rocks in Japanese rock gardens are positioned using this same idea, where the rocks seem to connect along hidden lines with one another, evoking the sense of natural placement, of a microcosm of the larger universe.[3]

16.5. Alternating contexts (spatial and temporal)

With *alternating contexts I only wish to make a simple but important point: *narrative figures / *ToM / people move and pass through time, and in so doing, constantly change cultural contexts. If these entities were simply perfect mirrors of their environment, this would make interpretation easy: we match the *ToM to the current cultural state, for example. But this is not how it works. Instead, narrative figures, *ToM, and people all bring the prior and future locations (in time or space) to bear on the current situation. When I moved to Kyoto, I brought “America” with me. And when I moved back to California, I brought “Kyoto” with me. Here at Berkeley, I am mostly a Berkeley person. But not entirely, of course: there is some Oklahoman in me, and Tokyo, and Kyoto, and Bodh Gaya, and so on. There is my visualized past and my expected future. There are the cultural environments created by my circle of friends, circle of colleagues, imagined and real. As we think, feel, make decisions and predictions, we often measure these many contexts against one another consciously, but no doubt they continue to influence us even when we are not particularly paying attention.

16.6. In sum, how do we deal with pluralities?

When analyzing we cannot possibly make a catalogue of all possible contexts, whether *autonomous, *competitive, *layered, or *alternating, and collectively called in this chapter *pluralities. They are outlined to eliminate some of the confusion that arises when we begin to explore contexts, and to energize our curiosity toward identifying a range of contexts rather becoming satisfied with just the most obvious, and because I want to make a statement as to what I think is really going on when we talk about “cultural influence.”

However, as a practical matter, we should neither seek the simplest of answers nor consider things so endlessly that our analysis collapses under the weight of its details and tentative conclusions. We should, in short, use good judgment in deciding what matters.

Finding balance among many possible scenarios and conclusions is probably the essence of all good analysis.

- Peter MacMillan, trans., The Tales of Ise (Penguin Books Ltd., 2016) 7. Kindle Edition. ↵

- Both translations are mine. ↵

- Gert J. van Tonder, "Eight lessons from karesansui," In Proceedings of The First International Workshop on Kansei, Fukuoka Japan (February 2-3, 2006), http://www.zen-garden.org/documents/8lessonsfromkaresansui.pdf . ↵