Memories, shared memories, cause-and-effect in narrative segments

— Terms —

- Introduced:

- cause-and-effect chains

- narratives (texts)

- Mentioned and should now be familiar (review if necessary):

- worldviews (cosmic and social), ethical values / common practices (WV/CP)

— Chapter Abstract —

This chapter explores the role of memories (including patterns associated with or derived from past events) in the interpretive process and offers four types of memories: subject (self)-based memories, quasi-shared memories, shared memories, and extra-personal memories. The line of argument offered is that memories extend beyond the boundaries of the individual and, in so doing, are social entities which means that they are entangled in culture. In a second consideration of time elements in patterns, narratives are described as cause-and-effect chains and that their progress makes sense to us when these chains follow lines that meet our understanding of worldviews and values. This in this case as well culture provides the context for a narrative to “make sense.”

— Chapter Outline —

- 9.1. Memories as doorways to cultural influence

- 9.2. Cause-and-effect chains

9.1. Memories as transpersonal doorways for cultural influence

Memories are complex cognitive events. Since this is a course about interpretation, we would travel too far from our topics if we become over-involved in the neurological structures and processes that support memories. Rather, for the purposes of this course, we need only to understand how memories are a component of a cognitive pattern (as object or process) that brings meaning (including affective meaning) to the selected object.

In this role, memories are the lifeblood of “understanding” in two ways. First, and importantly, memories allow us to bring to bear on the object previous understandings of similar objects, making our interpretations often nearly instantaneous (whether accurate or not). We know a mosquito when we see one (memory of our interpretation of a previous “thing”) and we know that, if it lands on our hand it might bite (memory of a previous “event” / process). Roughly put, memories are not just memories of static objects but also of events that play out across time and often include a *cause-and-effect interpretation. Memories are the crucial elements of an interpretive moment that un-freezes us in time and allows us to bring to the brief interpretive moment an expansive cognition of time, giving dimension to the object and situating it within a narrative, however complex or simple: “that is my friend, who also waved hello yesterday,” “this is where the tree fell last week and those flowers must be in memory of the person killed by that tree,” “this coffee is good right now but I should drink it soon because it is the type the gets sours quickly,” “I can only see the back of this person but I know the face because I’ve seen this person before,” and so on. Second, when we encounter something unfamiliar to us either because the object is poorly or only partially within perceptive reach (the object is not *robust), memory allows us to coordinate data we gather from one moment to the next (such as various visual angles of a mysterious object) until we have enough data to settle on an understanding, or a deeper understanding, of what the object is, an understanding that often includes future prediction.

Considering how memories deliver meaning to objects of the moment (and usually without a critical reconsideration and perhaps even unconsciously), it is not difficult to see how misinterpretations can gain a hold on an interpretive process: we decide what an object is, then next time we encounter a similar object we rely on the previous memory to determine what this new object is, and after a few events like this our understanding of such objects begins to have a sensation of certainty—a misinterpretation becomes a confirmed understanding that is no longer critically evaluated. In this way, memories both enable, shape, or derail accurate understanding.

But memories do not simply arrive at the “end” of an interpretive process, as in “What is that? Oh, I remember it is a ….” Rather, memories are hermeneutically and profoundly involved in object *selection and *organization. What we remember can be the guide to what we will notice of an object or how we array objects. What we remember and what we “see” before us are intimately entangled. Memories, being themselves the products of interpretive processes, already have encoded in them cultural *worldviews and *values. As hybrids of selective object details, generic pattern components, cognitive habits, and tested interpretive outcomes, each with a vital relationship to time, memories are encoded perspectives and opinions fully incorporating cultural influence.

One way to sharpen our thinking of how culture participates in interpretation via memory deployment is to generate a simple typology of memories that might carry cultural positions. We can set aside the consideration of relatively culturally neutral memories such as where I left something yesterday, or that I teach at 8:30 on Wednesdays, or that I need to buy something for dinner on the way home. Because this class focuses on cognitive representations of cultural differences, we can also set aside, for the most part, memories that are highly charged with primal emotions that are common to us all, such as traumatic events. But if the memories are populated by human subjects, and if human subjects are shaped in part by the cultures they are in, then all of the below memories, if recalled as part of the interpretive process of a current event or constructing identity are already laced through with cultural bias that work, probably unconsciously, in determining the interpretive outcome. We might want to keep these four types in mind (below, “subject” means the individual recalling the memory):

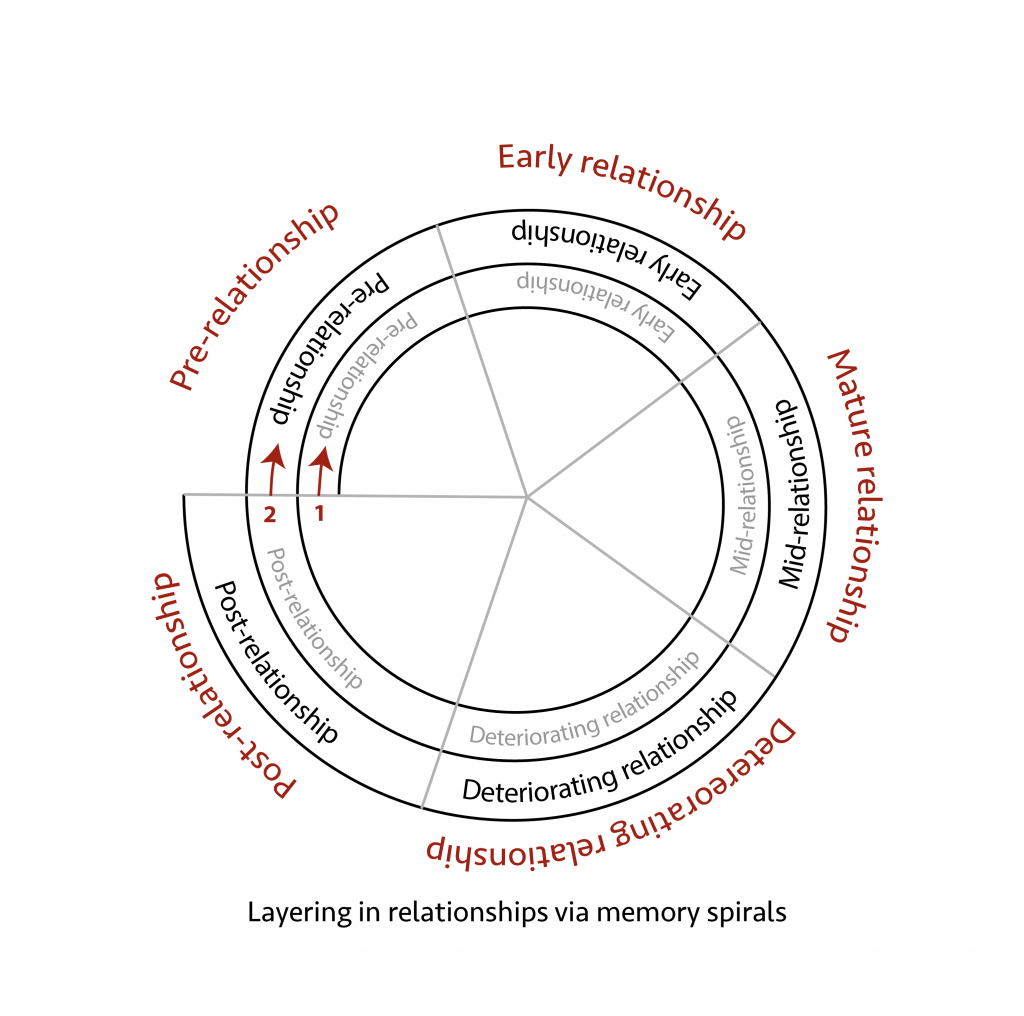

- Memories where the subject is the center of the event or narrative and any other human has weak or no representation: “things that I did or happened to me.” For example, one might misperceive a fly is a bee because one fears bees and tends to worry they are there when they are not, thereby warping the pattern matching. Closer to our topic, one might conclude not to trust someone because of one’s current constructed memory of past events (that may or may not have warranted the conclusion that people cannot be trusted but that interpretation is already associated with the memory). In this way the past, or at least our current understanding of our past based on how we recall it now, colors the present in increasing layers of complexity the more the past penetrates into the present. For example, if we are early in a relationship we might recall what it was like to be early in a prior relationship and it might change how we interpret our current situation including our predictions of the future of the current situation. In this simply schematic diagram, “1” represents the first relevant relationship, while “2” is the current relations and the spiral shape is meant to suggestion the on-going production of memory layers as we become involved in still more relationships.

- Pseudo-shared memories where the subject is engaging in or being affected by others: “our day at the beach” “that you never answered my email” and so on. These are “pseudo” in that it does not matter if the other persons represented in the subject’s memory even remember the event, or remember it in the same way. Though not necessarily the case, these can be powerful representations of cultural values. For example, one might remember one’s father might be a white-collar crime prosecutor and is as always warning never to trust people who have a lot of money. This is a worldview of how the social world works and is often deeply colored by an individual’s cultural memberships.

- Shared memories, such as a couple’s history of their time together or family memories: “our day at the beach.” In this case, whatever happened at the beach is an “official” part of the couple’s history. They have discussed it and decided how to remember it: “Yeah, we left because the wind was cold and the sand was blowing into our food but we still had fun trying.” Now the memory is something like a memory-contract between them. Each knows this is how it is supposed to be remembered. The dissolving of a couple can involve rewriting of these shared memories. “I always thought it was a stupid idea but he insisted that we go.” In this case the worldviews and values of another person have, by mutual agreement, been accede to partially or wholly, becoming part of the “world” of those individuals. Your interpretations follow pathways that have been mutually determined.

- Extra-personal memories, that is, memories that belong to a group even if the subject never actually participated in the event, such as a country’s collective memory of the Japanese occupation during World War II, or the shadow of American segregation practices on current race relations: “these things happened to us” (rather than “these things happened to my parent’s generation”). I once had an Armenian student who said he would feel dismay if his son did not embrace his own resentment of the Armenian genocide of the early 20th-century because it was an essential part of Armenian identity.

These types of “memories” do not personally belong to the interpreter. Most of us learned the meaning of a stop sign either through a written definition of it or watching the behavior of others. We learned the full, 3-dimensional shape of it through direct observation from many angles, collectively remembered as “the various way a stop sign might look.” However, when I was in graduate school, I bicycled to classes. I was told by others that there were certain intersections where police stationed themselves during the first couple of weeks of the new academic year so as to ticket people like me for running the stop sign. This is a “collective memory” developed through the personal observation of some and passed around within the cultural group. Personally, I only saw this once but I still had the benefit of increased certainty based on repetition of the event via the collective memory of others. Memories can exist as interpersonal networks of meaning and, in so doing, can contribute powerfully to the content of a cultural group. Culture spreads horizontally through a group and vertically down through time via these extra-personal memories appropriated as one’s own memories with one degree of separation. (The premodern auxiliary verbs “ki” marks that an event has occurred in the past. However, while “ki” is for personal memories of events if the information is heard from a source taken to be sufficiently reliable “ki” might be used anyway, as if it was one’s own personal memory.) In this way, what one thinks of as “my” memory or purely “what someone else remembers” is subjective. This is not about whether one is actually in the memory in some way. The point here is about how subjectively “close” one holds the memory to be. In that category, the “my” of “my memory” does not have all that distinct a border between “me” and “others.” The occupation of one’s country, current or as a past event, can be held close (and so influence interpretations) as one’s own relevant memory, via a close identification with the occupied group.

While memory is key to interpretation, memories (as touched on above in the discussion of object selection) are subject to drift—the memory we have now of something is not the same as the memory we once had of that same thing, nor is it the same as the thing itself. This drift is not simply the product of the memory fading; rather, who we are now, including our moods, and the cultural environments that provide the contexts for our thinking are involved in our “recovery” of a memory which in many cases would be better described as a reconstruction of a memory. (In terms of the actual brain processes, memories do not reside in a single location but are recalled by the coordinated activation of networks of neurons across various areas of the brain.[1]) Memories can overcome the interpretive bias of a present situation or participate in that bias.

Further, we may or may not know that a memory is involved in an interpretation. For example, one explanation for the subjective sensation of déjà vu is that we have encountered a new situation so closely matching a past memory-pattern that we feel we have already experienced that space and what is happening or about to happen. According to this hypothesis (tested and supported by experiment), a spatial pattern very close to the actual environment we are in is in the background, affording an eerie sense that we have been here before, and, sometimes, also feel we know what will happen next.[2]

9.2. Cause-and-effect chains

As suggested by the discussion, memories enable us to store and perceive patterns that stretch across time segments. Movement, repetition (and discontinuity), and processes are all patterns with time elements. Of these, our course most closely looks at cause-and-effect pairings and chains of theses. Our brain anyway is naturally very interested in these since an understanding of cause-and-effect gives us strategic advantage, leads us to pleasure, helps us avoid pain and danger, helps us understand current and past events, and so on. such as movements and processes. However, our analytic interest in them is more specialized than this.

The definition of “narrative” in The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms begins, “A telling of some true or fictitious event or connected sequence of events …”[3] There are many different ways of thinking about narratives. If, for example, we were to focus on the “telling” portion of Oxford‘s definition, we become involved in issues of narrative technique as we explore how and by whom the narrative is delivered to us or others. “Interpreting narratives,” for this course, is primarily as follows. We provisionally accept two pre-conditions: first, that a narrative “event” has a non-absurd (non-random) framework of cause-and-event. That a writer is motivated to construct narratives that make sense to the reader and so will create code that are amiable to the reader’s repertoire of cause-and-effect sequences. If I read, “I flew an elephant to work today,” I might struggle to situate this within my repertoire of cause-and-effect sequences (because I believe flight cannot be enabled by elephants) if determining sense is important to me for some reason. Is it metaphor? Is it code? Did I misread? (Perhaps I’m reading in another language.) Is the speaker making a joke? Or demented? I have options and I will settle on a range of possibilities and have a sense of how likely my interpretation is. However, if I was told that sentence was the output of an AI program being built by a student who is still working on getting the program right, I’ll just dismiss it as an absurd narrative that doesn’t require a good cause-and-effect explanation. In this way, we are interested in “making sense” of the narrative and what we use to arrive at a sensible interpretation includes our worldviews and values. Thus, seeking to “make sense” of a narrative along lines that we are comfortable with explores our own way of seeing the world while “making sense” of a narrative from the author’s perspective, as we can best guess it, asks us to have an understanding of the author’s worldviews and values. Thus, exploring cause-and-effect chains is a good exercise is identifying, articulating, and measuring worldviews and values, both of which are fundamental components of a group’s culture.

Imagine that we encounter this sentence: “Caring is an advantage.” To interpret this sentence, we want context. Did a student say this? Was it spoken in a horror film? Was it the first thing one of the two lovers-to-be in a romance film said to the other, over a drink? … These questions seek to identify a culture group and a specific situation, so we can try to deploy some of the values of that group to establish a plausible meaning. That is, we are exploring a cause-and-effect relationship: why were these words uttered? (The meaning of the words themselves is not difficult.) Actually, sentence was generated just now for this paragraph, via a bot[4] that uses, as part of the algorithm to generate apparent wisdom, the principle that juxtaposition creates an effect of mysterious or deep meaning.[5] That it is bot-generated does not make it random. The computer program team that created the website was trying to create a program that would imitate what these two Norwegians saw as some of the stock inspirational quotes that were often passed around on the internet. So their perception of the world suggested, collectively, by these types of quotes plus their own Norwegian ways of seeking things, plus each engineers personal view of things have mixed together to give, as they say, a “personality” to the quotes generated. Further, this context could be ignored entirely and you, as a reader, could attribute your own significance based on either your best guess of context or your own way of seeing the world, or, most likely, some blend of these. In any event, speculating about plausible cause-and-effect sequences is our primary way of trying to ferret out the possible worldviews and values of a narrative or, more specifically, the worldviews and values of a character within the narrative, the narrator of the narrative, the author as constructed by us, or model readers as posited by us, or ourselves.

- "Therefore, contrary to the popular notion, memories are not stored in our brains like books on library shelves, but must be actively reconstructed from elements scattered throughout various areas of the brain by the encoding process. Memory storage is therefore an ongoing process of reclassification resulting from continuous changes in our neural pathways, and parallel processing of information in our brains." Luke Mastin, “Memory Storage,” in The Human Memory, 2018, http://www.human-memory.net/processes_storage.html. ↵

- Anne Manning, “Déjà vu and Feelings of Prediction: They’re Just Feelings,” Colorado State University: College of Natural Sciences(blog), March 1, 2018, https://natsci.source.colostate.edu/deja-vu-feelings-prediction-theyre-just-feelings/. ↵

- Chris Baldick, “Narrative,” in The Oxford Dictionary of Literary Terms (Oxford University Press, 2008), http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199208272.001.0001/acref-9780199208272-e-760. ↵

- “InspiroBot,” accessed January 29, 2019, https://inspirobot.me/. ↵

- Ira Glass, “Why I Love InspiroBot: Prologue,” This American Life, December 5, 2018, https://www.thisamericanlife.org/extras/why-i-love-inspirobot. ↵