always about high-order love ◆ narrative worlds, not "real" worlds ◆ ToM as litmus test ◆ short-listing

Key terms introduced in this chapter:

- no new terms are introduced in this chapter

Key terms mentioned in this chapter that should now be familiar:

- affective love

- CDE report

- cognitive love

- cultural contexts

- East Asia

- emergence

- high-order love

- horizons of expectation

- interpretive projects

- love

- low-order love

- model readers / viewers

- practicability

- shareability

Managing *interpretive projects has been discussed previously in a chapter devoted to the issue. Managing our projects is key in terms of *practicability, *shareability and best positioning the work so as to invite discovery and insight. This chapter steps through one more time the principle ways we limit the scope of *interpretive projects so that they are doable and can be easily shared. Further, limiting the complexity of the project helps reduce the fog factor associated with our difficult topic and it is my hope that reducing such distractions and confusions enhances opportunities for insight.

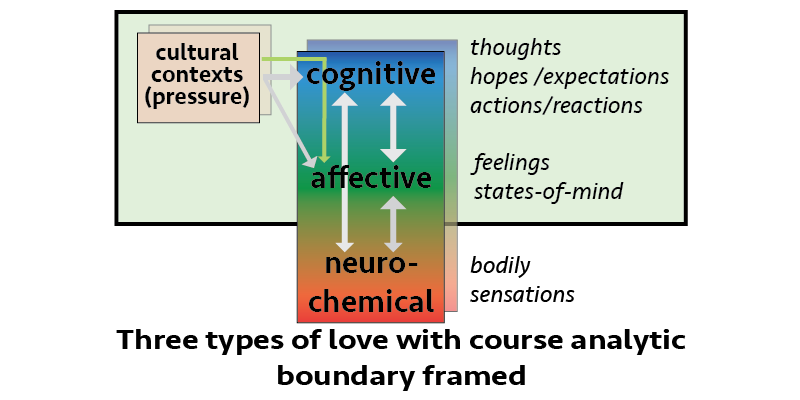

21.1. The “always about high-order love” standard

We are indeed exploring cultures of *East Asia through the interpretation of film narratives, but we are not exploring just anything about these countries or their cultural terrain. We have restricted our topic to “*love.” The “*emergence blossom” graphic indeed suggests that *love in its highest expressive form in a narrative is an *emergent effect of a variety of elements, including anxiety, loneliness, war, selfish behavior, desire—well, the list goes on and on. We have determined that we are not trying to capture this full expression of love that would require an extensive exploration of all the cultural contexts of all corners of a narrative. Instead we focus on *cognitive love but with a willingness to discuss *affective love when necessary. Ask whether the initial line of inquiry by you or your group—the analysis as it plays out in your mind or in group discussion, or the conclusions you or your group might arrive at—have met this standard: Is the topic at hand meaningfully and directly relevant to *high-order love?

It might be a good idea to repeat an earlier graphic that shows the boundaries of what we seek to analyze:

21.2. We analyze narrative worlds, not “real” worlds

I have discussed elsewhere my view of the porous border I perceive between narrative worlds and this “real” world as well as how similar I view the two to be. That being said, we nevertheless limit our attention to narratives, not the real world situations that they might suggest. This relieves us, to some degree, from the obligation to develop expansive, real world descriptions.

21.3. ToM as litmus test

It is not just that we limit ourselves to narratives. We in fact limit our concerns to just one aspect of narratives: things related to *cultural contexts.

Yet, there are almost always a dauntingly large number of possible *cultural contexts. We want to gather widely so that we do not skip over something not obvious that might help us have a keener understanding of the situation, but we do not want to be confronted with long lists of possibilities.

Thus, we tie our decisions of what to consider or not based on this: Will it tell us something that is not already obvious about the *status of the *ToM’s *traditional *worldviews and *values relevant to *high-order love? Yet even this is not specific enough. If we imagine the *ToM to be the central character of the film, surely that character goes through hundreds of thoughts, feelings, and decision-making acts or reactions and we do not want to be obligated to consider the *cultural context for each and every one of these. If we limit what we consider by deciding film themes, we are just playing into the hands of the author / director. We want a more independent stance. Therefore, we instead settle on an *instance, restricting our speculation to a specific “moment,” avoiding the endless work of considering the entire narrative or the already heavily prejudiced (culturally-embedded) space of the themes of the film. Is should be said though that this “moment” is not just a simple point in time. Things are not that easy. It has a broad definition in this case, one similar to the use of the word in sentences like this: “There was a moment in U.S. history when the practice of slavery was called into question.”

Of course, to understand this instance we still need an expert understanding of the film as a whole, including almost certainly some knowledge about the director, perhaps also about the audience, and perhaps even other films that are referenced by this film or film genres that are influencing the film content or its place in film history. An *instance is not divorced from these contexts. Thus, limiting ourselves to an *instance is not as much of a rescue as it might first appear to me. It is still better than taking on an entire narrative and we are freer, so to speak, to pick our fights.

As we engage in the work of gathering *cultural contexts, we establish their distance and array them in relationship to the *ToM. Once this is done we probably have only one, two or at most just a few *cultural contexts that we need to understand and we also know which should be the primary focus of our concern and how they are interacting with one another. Our project has become manageable at this point.

However, I would like to close this section with a return to the previous limiting question: “Will it tell us something that is not already obvious about the *status of the *ToM’s *traditional *worldviews and *values?” Once an *interpretive project is actually underway, it will become immediately obvious that it evokes all sorts of non-traditional *worldviews and *values that we need to consider. *Status does not exist in a vacuum—some sort of *worldviews and *values will give structure to a narrative—it is just a question of which ones. So, establishing the *status of a *traditional *worldview or *value means, in practice, measuring it against the *status of some other *worldview or *value.

21.4. Short-listing

21.4.1. Short-listing through narrowly defined topic

An *instance, as will be discussed below, is an aspect of a narrative that seems to have a heightened opportunity for exploring *cultural contexts. The best *instances will be highly evocative and suggest a number of different lines of analysis. In order for all working members or working teams to be pursuing analysis whose results are relevant (credible and interesting) to one another according to the *shareability principle, those lines of analysis should be within range of one another (topically speaking, not necessarily in terms of their conclusions). So, we bring to an *instance a *narrowly defined topic which is essentially a short list of things we think are worth investigating. The topic becomes our mutually agreed upon written contract as we say goodbye to one another and disappear to do independent research and analysis. It sets us off toward specific investigations that hopefully will lead to discovery or insight that coordinates with or challenges the work of others, once interpreters are reunited. Please note that “discovery or insight” is a phrase that is intended to block a research paper approach where the conclusion is imagined and then research is done to support and prove the conclusion. A proper *narrowly defined topic will never pre-decide the outcome. It limits the direction of the research but should never limit the potential conclusions of it, thereby leaving space for discovery. Without this open-ended quality, the diversity of a team cannot be leveraged effectively, blindnesses cannot be overcome, *horizons of expectation cannot be moved.

21.4.2. Short-listing interpretive conclusions with shareability in mind

The interpretive method is designed to enhance lively discussion. In its ideal form a group of diversely thinking individuals who have considered the *narrowly defined topic with some discipline and energy have generated a variety of observations, big and small. For a *CDE report, they need to decide what of that has the greatest value beyond the borders of their group. This is the final short-list in the method and a very important one. It is the comparison of these short-lists that can (sometimes) be very revealing as to the actual, relevant cultural terrain of the *instance, and most likely well beyond it.