Constructing ToM ◆ seeing ourselves and others in narrative figures ◆ making sense of narrative developments

Key terms and concepts introduced in this chapter:

- bumps

- “making sense”

- model reader / model viewer

- narratives

- narrative figures

- narrative progress / cause-and-effect chains

- scholar-beauty / caizi-jiaren storyline

- Theory of Mind (ToM) / mindreading

Key terms and concepts mentioned in this chapter that should now be familiar:

- attractors

- Connectivism

- cultural contexts

- common practices

- East Asia

- ethical values

- “horizon of expectation”

- models

- worldviews

14.1. Mindreading / Theory of Mind (ToM)

We explore the cultures of *East Asia by looking at what *worldviews and *ethical values might be present in stories and films. We try to identify these *worldviews and *ethical values by constructing plausible *ToM for narrative figures (*mindreading)—work that is not much different than what we would do about others in our daily lives. We try to understand narratives when they move forward in ways that feel unnatural to us by checking whether different *worldviews and/or *ethical values could explain the developments better.

14.1.1. Mindreading: Constructing ToM

Early in the Chinese film House of Flying Daggers, Jin (one of the two key male protagonists of the film), dressed in disguise, forces his way into that part of the prison where Mei (the female protagonist) is held. In a dramatic fight sequence, he frees her and they flee together. In a scene before this one, Jin and his comrade soldier Leo had secretly decided that if they free Mei, she will return to her rebel group (the Flying Daggers), thus revealing their location. in and Leo ill thus be able to collect a reward for their work, and, too, government troops will be able to mount a successful attack on the rebel group.

Once safely deep in the forest, Mei has an opportunity to ask why Jin freed her. He answers that because she is exceptionally beautiful he would do anything for her, and that, anyway, he hates the government and respects the Flying Daggers.

As we watch this scene wondering whether Jin has just lied to Mei or revealed a twist in the narrative, we are making these mindreading calculations:

Based on the film so far, the exceptionally handsome Jin should be taken to be a playboy. We factor that in. Jin appears to be loyal to the government but not so very loyal. We keep that in mind, too. Given these things and the exceptional beauty of Mei and the warm that seems to be between them, plus our knowledge that films like this enjoy having twists and turns in the story, it seems unlikely but within the range of possibilities that perhaps he really would prefer to escape with, and take ownership of, a beautiful woman as opposed to continuing to labor as a soldier—a role he does not seem excessively proud of. Further, we have already encountered instances of deception in the film and so that should be on our mind. Some viewers at this point will decide one way or the other on the point of Jin’s truthfulness while others will be more tentative and continue to wonder about his faithfulness which is, indeed, one of the themes of the film.

What of Mei? Does she really believe him? Is she so confident of her beauty or cynical about the intentions of men to believe Jin’s explanation? Perhaps she has decided only to appear to believe, in order to trick him for her own reasons? Her verbal and facial expression and body language are all convincingly one of trust. Because she is a sympathetic (and beautiful) and blind woman, many of us will identify with her and think of her as in need of protection at this point and conclude that she is indeed trusting him. Other viewers might be more cautious but will not be able to decide whether the caution is warranted of just a result of a naturally more cynical approach to film narratives.

The information we draw in our attempt to mindread these individuals is surprisingly extensive: What sort of film is this? Is it a “straight” story or will it have lots of twists and turn? Since it is a martial arts film, we rather suspect it will. And, since it is a martial arts film, loyalty to one’s fighting group probably is an *ethical value that we need to give some weight to. But since it is in epic Hollywood style perhaps, we wonder whether it could just be more “American” in its approach, whether, for example, it is a film more about choosing what is good for yourself than submitting to the demands of a group? Should we, in other words, deploy some set of Chinese sensibilities or some selection of American sensibilities in predicting plot development? We might ask ourselves again what type of person do we think Jin is. (We go back in our mind and review his past actions and attitudes.) And do the same for Mei, too.

We can do such mindreading in an exceptionally brief period of time—seconds. It is what we do with regard to the actions of others all the time, a secondary nature habit of calculation that gets us through our days and is key to how we will interact with others. This film is designed, in particular, to invite us to mindread. If it has captured our interest, we are watching and thinking of both Jin and Mei “Why did you do that?” “What will you do next?” “How will you react?” “What are you feeling?”

We are engaging in something that we will call “constructing *Theory of Mind (ToM).” We are guessing what a person might do based on what we know of that person, including what we think that person believes, what state-of-mind is in play, the immediate demands of the situation, and so on.

Let us consider a passage from “Journal of Bleached Bones in a Field” (Nozarashi kiko) by the 17th-century Japanese haiku poet Matsuo Basho:

I was walking along the Fuji River when I saw an abandoned child, barely two, weeping pitifully. Had his parents been unable to endure this floating world which is as wave-tossed as these rapids, and so left him here to wait out a life brief as dew? He seemed like a bush clover in autumn’s wind that might scatter in the evening or wither in the morning. I tossed him some food from my sleeve and said [composed this haiku] in passing,

those who listen for the monkeys:

what of this child

in the autumn wind?[1]

The reader might feel something odd or strange in this passage. The generic *ToM would suggest that a poet (a person with deep feelings) who is bothering to tell us of an abandoned child, would do more than toss the child some food, write a poem about it, and move on. We can, at this point, just conclude Basho is a cold person, or we can conclude that there is something more to understand about him. We know we lack sufficient information to decide which, so usually, unless there is a good reason to do otherwise, we will just move on, but with some unfinished business in our mind and some doubts about him. Our operative *ToM might be something like: “Hmm, I don’t know what to think. Maybe he is cold. I think I would have tried to help the child or at least tried to ask someone something.”

If I were to assert that Basho is illustrating the Buddhist truth of karma (he showed interest in Zen Buddhism all of his life)—that our current condition is one of fate that we must accept—, it might change how we construct our *ToM. If I were to assert that, based on his writings, it is clear that he is deeply interested in and informed about Chinese Daoism, that, too, might change our construction. Initially, most of us probably did not think to deploy Buddhist or Daoist *values as key to the passage. We have perhaps important new details about Basho’s *worldview or *ethical values. But, still, the revised *ToM would be something like: “Basho probably is someone more interested in narrating a moment of Buddhist truth or an affirmation of Daoist *wuwei, than exploring the possibilities of action-from-compassion (which is better associated with Western notions). Yet, if that is true, what sort of person is that?” Puzzles remain. We haven nogt *made sense of the narrative yet to our full satisfaction. That lack of satisfaction is either marking undecidedness about the *ToM or disagreement with the *values needed to make sense of it, or both.

If we want to construct a *ToM that best matches one a reader of the day might have constructed, we should keep gathering contextual information. We might learn, for example, that it was a time of famine. This abandoned child may be just one among many, too many, abandoned children. Now we might be able to forgive Basho his actions, deploying the generic principle, “Sometimes there is no solution to a problem. At least he offered some food” or use to that same end the more Japan-specific notion of *akirame (“giving up/letting go”—based on the Buddhist and Daoist wisdom of accepting fate).

But that he wrote a poem still strikes a somewhat dissonant note. If we learned that Basho devoted his life to writing haiku and continued to do so even on his deathbed, and at every significant moment of his life (and many that were just casual moments), we could further revise our *ToM to something like this “Basho’s most sincere and deeply felt way of expressing his thoughts and emotions is through poetry. Perhaps he is truly distressed, but understands that there is nothing he can do.”

Now we have constructed a Basho that “makes sense” to us—we have assembled sufficient contextual information and applied it in a way that puts his actions within reason even if we feel we might behave otherwise. But perhaps we have gone too far in reconstructing a Basho that comfortably matches our own *values. Perhaps we have been unaware that we have deployed an assumption: “A poet is someone who has sympathy and empathy.” Or perhaps our preconceived idea of children is that they are small, helpless creatures whom we are duty-bound to care for. Perhaps, on the contrary, Basho really is just a cold poet. Perhaps he thinks, “children are just really not that much my business.”

I hope you can see how, in this case of Basho’s tossing of food, we are shuffling around *worldviews (the Buddhist concept of *karma) and *ethical values (starving children should not be abandoned except in certain cases), measuring the against each other, in an attempt to “*make sense” of a narrative moment rather than just leaving it as “somehow odd” and that you can see, too, the perils of simply deploying one’s own *values onto the narrative moment. We are engaged in a similar balancing act with Jin: Handsome men who seem to love women are not that likely to take their loyalty oath to a government as the primary deciding factor. Is he really a playboy? Is he really a good soldier?

Compelling narratives often offer up these “in the balance” situations where we want to understand but are not sure. *ToM remain interestingly unsettled and we keep reading or watching to see how things will play out. We are constantly presented with the undecidedness of a *ToM, the possibility that we have calculated incorrectly based on lack of information or through error in applying context. While in the real world it can matter when we are wrong, luckily for this course the very act of building a *ToM is the point. If we consider one possibility then change to another and end up not being sure it is not a problem as long as we have traveled the road of asking what *worldviews, *values, and *common practices should be considered. By doing so, we are sharpening our interpretive skills, discovering what others think, and learning (usually traditional) cultural content that might be more relevant in our daily lives than initially thought.

14.1.2. Some words of caution about ToM

Constructing *ToM is one of the key activities of our *course method of interpretive analysis. (Another is identifying a useful instance to analyze. Still another key activity is assembling—discovering and mastering to some degree—relevant contexts, such as the Buddhist *worldview that ours is a world of illusion.)

There are two basic types of *ToM and both are important to us, though for different reasons. In the discussions about these two general types a variety of terms are used but commonly one set is termed “simulation-theory” (or “mental simulation”) and the other “theory-theory.” These are shorthand appellations to suggest that one develops a *ToM—a “theory” (that is, a predictive model) of how a person is thinking, feeling and acting—either by running a “simulation” within one’s own mind, or building a “theory” based on basic principles of psychology. (So, yes, “theory-theory” is oddly redundant. The somewhat humorous name arose during the debates and criticisms around these theory, in order to distinguish it clearly from “simulation” approaches.)

When one tries to predict another (construct a *ToM) by asking the question, “If it were me, I would …. ” what we are doing is simulating the situation within our own cognitive space and projecting those results onto the *ToM we are building. “If it were me, I would be angry if the professor would not let me make up the assignment, therefore, I am sure my friend is angry, too.” “Simulation theory” actually works very well in most situations and is also, I would suggest, at the root of Freud’s idea of “projection” and (later) “transference” (where a patient projects onto the analyst also sorts of emotions, good and bad). Obviously, the danger is that I can easily over assume that someone will think and react similarly to myself. Clearly, this is especially true in cross-cultural situations.

“Theory-theory” argues that what is a better approach is to use principles (suggested from a range of sources, including basic psychology, social practices, and so forth) rather than our own minds (“me”) as the modeling (making a “theory”) material. The criticism is that such principles might be overly simple, even naïve.

“Simulation theory” helps us get our bearings in a situation, and probably is important to “locking down” the basic cause-and-effects chains that are the progress of a narrative. (We read and the narrative develops in ways that “make sense” to us.) However, “theory-theory” allows us to consider a person from a different angle. If we are not Confucian but the person whose *ToM we are trying to build is, it might be very useful to ask “What would a good Confucian think she or he should do in this situation?” We are applying a principle, not just asking ourselves what we should do.

*ToM theories has been challenged in the past couple of decades with a powerful argument that human behavior arises less from large meta-positions than from situational sequences.[2] If I sit at a table for a party, I might engage in friendly conversation with the person next to me not because of a principle or because I think this is what I imagine others might want me to do, but in simple reactive response to the immediate situation, namely, that the person is talking to me in a friendly way and I am responding to that warmth with my own friendly banter. This behavioral argument has the advantage of simplicity and explanatory flexibility: the line of behavior is situational, not derived from *ethical values or simulations that are based on, well, what exactly? And, the argument goes, if we observe carefully we see that much of our daily behavior is just like this. I find this criticism of *ToM to be convincing, and it is in line with my pedagogical interest in *Connectivism. But this actually is not relevant to the course because we are not trying to be cognitive psychologists; we are borrowing the act of interpretation (gathering and application of contexts) to explore the *worldviews and *values of *East Asian countries. To that end, the practice of constructing *ToM remains a powerful way to explore aspects of a culture.

So, for this course we engage in *ToM construction but with a heavy emphasis on double-checking as to whether some overlooked traditional *cultural contexts might be meaningful. In other words, we gather together, as best we can, what might be the relevant *worldviews, *ethical values, and *common practices for the instance we seek to interpret. This is the heavy-lifting part of the course analysis, since in many cases we simply do not yet know or know well enough the cultural context (such as the main *ethical values of Confucianism). Much of the work of this course is discovering, learning, and retaining awareness of cultural context to construct *ToM that show due appreciation and respect for the role of cultural elements in forming one’s thoughts, actions, and feelings.

14.2. Narratives

14.2.1. Narrative figures

14.2.1.1. Narratives and “us”

I will admit to a split interest in authoring this book and this course. I really like narratives and I enjoy trying to figure them out and make them interesting to others. (And love narratives are by far the most interesting to me.) On the other hand, I am fascinated with how people think and why they do what they do, or, perhaps more honestly, how our psyche works in all of its confounding complexity and what this means of the “human condition” and how understanding better might lead to kindness, thoughtfulness, and a peaceful, rich life. In terms more specific to this class, I see us all as trapped in our *cultural contexts, being more followers than leaders in life as we are guided by forces we are hardly aware of, forces that divide us and foster suffering of all sorts. I think humans are capable of good acts but more capable of them when they are aware of the forces around them rather than just letting situations decide their actions and moods. My interest in culture comes from a desire to understand more accurately ,and gaining freedom through that awareness, letting confidence and knowledge dispel fear and invite happy thoughts and good acts.

I would also like to put aside any niceties on this point: those who think literature, the topics of literature, the events in narratives—all of that—cannot lead us into meaningful thought about and the experiencing of “real life” are just, simply put, wrong. I would like to argue that the narratives of fiction are not very different from your very selves. That the boundary of our identity is most definitely an open border when it comes to narratives. That narratives, rather easily, “crossover” and reside in us, giving “us” fundament shape and substance. We absorb narratives. Reading narratives changes who we are.

I will offer three reasons for this line of thought: object relations, identity via narrative, and the special ability of artifice to capture reality.

14.2.1.2. Object Relations Theory

“Object relation” is a key element in the theory of self offered by the mid-20th-century psychoanalyst Melanie Klein. She was primarily interested in the development of the self and how it builds internal structures that overcome self-destructive tendencies present from birth (Thanatos) in order to live healthy and full lives. Essential to this process is the development of internal representations of objects and the integration of them. While I find Klein exceptionally pessimistic in the same way Freud was pessimistic late in his life, I am convinced by her assertion that we interact with the world through the mental images that we create and maintain: I do not have a direct relationship with “you;” rather, my internal image of “myself” relates to the internal image of “you” that I have. Of course, this image is not static (or should not be static) but it is not a real person. It is a construct. (You can see, perhaps, why I feel *models and *attractors have such interpretive power.) From this view, it is not far to the conclusion that images constructed by me of you, and the image I construct of a narrative figure, are both of the same substance. Both are images, cognitive constructs. Of course, there is a huge and important difference: you are living and as a living entity you can smile at me, yell at me, give me gifts, steal my car, all those sorts of things. But it is undeniable that viewers can fall in love, to some degree, with movie actors never met and readers can fall in love with characters in a novel whom they have never seen. We can celebrate when “our” team wins as if we, too, have somehow won. These mental images matter to us. Not just a little bit. A lot. And thus, our interest in celebrities, film characters, and the “people” we meet in literature is when the stories of those “people” somehow capture our loving attention and become, as internal mental images, invested with sufficient substance and vibrancy as to evoke thoughts and emotions about them. The positive way of representing this is to say that consuming narratives can be a hugely satisfying and enriching experience. The negative way of viewing this is to ponder how we are never anything more than an image to another person. I would venture to guess that many of you reading this paragraph have felt that, as some point in your life, you were treated more as an “object” than a person. But, to balance that, being with someone does matter. In person we communicate with each other through the chemistry of our bodies. In digital conversation we engage in complex communication that creates complex, subtle, and powerful understandings of one another. But, either way, my position is that narrative figures and those we personally know have, in some way, common representations cognitively.

14.2.1.3. Identity (definition) through narrative

Rightly or wrongly, Freud believed that although the unconscious is truly unconscious and cannot be articulated discursively, telling a therapist about one’s fears and aspirations, dreams, childhood experiences, and current relationships can outline problems that would otherwise be out-of-reach and that, even with just these slim outlines, progress can be made at toward ameliorating mental anguish. This came to be called the “talking cure.” Its fundamental element is sharing the narratives one has about oneself: “I am a wounded person.” “I am a young scholar.” “I was happier when I was living in Montana.” “My dog loves me.” Given my rather complete acceptance of the Buddhist position of no-self, I find this way of thinking who “I” am to be convincing: “I am who I tell myself I am.” This is narrative pure and simple. Originally, I was just interested in how psychotherapy might be able to unearth old ways of thinking about oneself (myself). That, if the old narratives could be unearthed, the unnecessary or outdated an inaccurate story loops could be turned off. But, as my involvement in literature deepened, as I saw that reading Heian literature had changed me in truly substantive ways, I turned this around: having a self is not living out a life formulated by childhood experiences but rather my life, my “self,” is the result of all the narratives pouring into me all the time. Some are shrugged off; others dive deep into my mind and lodge there. This view—that the self is a thin consciousness bobbing about uncertainly on top of a body and all sorts of cognitive processes never consciously represented—harmonizes well with my Buddhist conviction of “no-self.” “We” are the stories we encounter and consume. The psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva wrote in New Maladies of the Soul that her patients were becoming harder to cure because they were losing the ability to tell stories about themselves with affect (emotion) that they — the “inability to represent.”[3] This sentence was life changing for me, at least in terms of my professional life. I began to “see” how, in fact, my students were also becoming, over the years, less fluent in the stories of themselves. Or so I thought. And it was this that made me believe that teaching literature was the teaching of a fundamental skill: making one into a rich, interesting, satisfying self. I taught in this vein for more than twenty years. My view is different now—I think students tell complex stories of themselves in postmodern ways that Freud could not imagine, and that they are not affectless but the widely used posture of cynicism or disengagement can make them look so. But this has not changed my fundamental view that the boundary between the world of stories “out there” and the world of stories about myself “in here” is highly porous.

14.2.1.4. Artifice and metaphor

Recently an ex-student of mine shared with such enthusiasm his newly found interest in a certain poet that I bought the most recent volume by that poet and reread the poem my student had recited to me in the café with such feeling. It was titled, “The Moon from Any Window:”

The moon from any window is one part

whoever’s looking.

The part I can’t see

is everything my sister keeps to herself.

One part my dead brother’s sleepless brow,

the other part the time I waste, the time

I won’t have.

But which is the lion

killed for the sake of the honey inside him,

and which the wine, stranded

in a valley, unredeemed?[4]

A couple of things about this. First, I sleep within view of a skylight and see the moon at night very often. Nights with the moon and nights without the moon are, indeed, very different. Recently there was a total lunar eclipse. The room darkened and became like a different country. The moon at the window is indeed something to write about. And now that I have read this poem, the moon at the window has become more “something” about my life. Narrative has poured in. Second, when he was reading this out loud and reached the line “is everything my sister keeps to herself” I privately thought “Exactly!!” and began to listen with great care. I knew I was in the presence of accurate language. The best poetry is most definitely not vague language. It is accurate language that exceeds the ability to fully articulate it with ordinary discursive statements. It is metaphor that names something exactly, not metaphor tossed into an ether with the hopes that it will generate some sort of meaning or response.

Although there are many ways to talk about how art can represent life or “truth” more accurately than “life” itself can, for me the path to this view was through the 18th-century master playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon who wrote for the puppet theater and the kabuki state and said:

Art is something that lies between the skin and the flesh, the make-believe and the real.

Also:

Art is something which lies in the slender margin between the real and the unreal. [….] It is unreal, and yet it is not unreal; it is real, and yet it is not real.[5]

A scholar comments on Chikamatsu’s approach to art and appreciation for the evocative power of puppets like this:

As a human figure, the insubstantial puppet is simply unreal. When not actually performing on stage, it hangs on a nail, reduced to a pathetic and insignificant object. However, as soon as the puppeteer sets this pathetic figure in motion, it becomes a human figure that appears more real than real human beings. The otherwise empty outer layer of skin (himaku [skin membrane]) appears to envelop real flesh (niku). The puppet begins to possess both skin and flesh (hiniku [skin and flesh]). Chikamatsu competed with kabuki because he always wanted the performance of puppets, which consist only of himaku [skin membrane], to surpass the performance of kabuki actors, who have hiniku [skin and flesh]. Behind Chikamatsu’s way of reading the kanji for “skin membrane” as hiniku [skin and flesh] rather than himaku [skin membrane], we can see his decisive and enthusiastic attitude as a playwright of the puppet theater.[6]

Those who have seen a traditional Japanese puppet (bunraku) performance might be more convinced of these words that others. The puppets of that theater truly have a disturbing amount of “life” in them.

14.2.1.5. “Reading” culture through narrative figures

And so, yes, we are “only” talking about characters in films, narrative figures. Narrative figures are artifices, partial representatives of real people but not randomly constructed. They do indeed have some sort of life within us and it is indeed legitimate to construct for them *ToM. The course is founded on this premise but I think it is reasonable because we interact through the world anyway through cognitive images, we identify closely with narratives, and art manages to explore in accurate and powerful ways aspects of the human condition. My view of the writer-reader (director-viewer) contract include that part of the artistic activity is that the author, of whoever, puts before us a proposition: Here is my view of an aspect of human thought, feeling and behavior. This is what we humans are. Have I convinced you? And with these narrative figures as mediators between the way the author understands life and the way we understand it we have, at hand, the possibility of discussing our differences in worldviews and ethical values. We can answer, “Yes, I see it that way to” or “No, I am not convinced.” Either response embraces our measurement of our own worldviews and values and those that we think the author, or the narrative figure (if at the level of the story) is engaging (where “engaging” is accepting, ignoring, or resisting — all work just as well for exploring differing *cultural contexts.

14.2.2. Building sensible narratives

14.2.2.1. Interpretation as the building of plausible and likely cause-and-effect chains (narratives)

A work of literary prose is, empirically speaking, just words on a page. It is in our mind, through cognitive processes, that they become narratives. (Thus, the relevance of *attractors.) No matter how many words there might be on the page—no matter how specific, detailed, rich, and complete that code might be—it is still a code, a system of signs. Narratives are born of the reader’s cognition. They do not reside in the page. The code content does limit our possible interpretations but this system of signs does not do the work of narrative building for us.

In this course, we call such building of narratives “interpretation.” Essentially, we are consuming the code of the written word or the many codes delivered simultaneously in film (sound, image, dialogue, and so on) and deciding, according to rules of plausibility and likeliness, the thoughts and feelings associated with the narrative figures as well as what might be the meaning of the sequence of events. We check this understanding with others to see if they agree. Our rules of plausibility and likeliness include our estimation of how others with whom we share our thoughts will think. The process is the same whether there is little code or much code, although how much we are limited by that code can differ greatly from work to work, even within a single work in its many passages.[7] A “right” interpretation of a work is one that others also find credible, and an “interesting” interpretation is one that others find interesting.

In our class, the “others” in the above sentence are, ideally, culturally well-informed, competent in building narratives, members of the relevant cultural group or groups (usually the target audiences of the film). When our interpretation seems at least plausible and, better, likely to them, we have succeeded in seeing the narrative from their cultural perspective. While this is the definition of interpretive success in this course, please note its Achilles Heel: If everyone in the group to whom you have offered your interpretation does not know well the culture that is the target audience, then simply because everyone agrees with your interpretation does not mean others more culturally competent will also do so. Put bluntly, your entire group has generated an implausible or unlikely interpretation. Yet, we can only make our best effort, and leverage the cultural knowledge of our group as best we can. We do not need to worry much—the process itself has great value, even when the results come up short.

I would like to continue this consideration of building narratives with a short exercise in such building. Here is a famous, short (code-sparse) sentence: “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.”[8] Please think for a moment and build a narrative based on this sentence. Then, when ready, keep reading.

We have only one moment in time. All the rest of the story is constructed by the reader. Why were the shoes never worn? Why are they for sale? We provide possible scenarios and in so doing, we create causes for the effect, narratives are born. The many plausible chain of causes that I might consider to get to the above result are drawn from my total experiences of the world (including the literary world) that I think will also make sense to whomever I plan to offer my interpretation (real or imagined). If I am serious about asserting my interpretation in a way to convince others, I will further narrow these chains down to those that are likely, as understood by me and whomever I plan to offer it to. The lack of sequential details (the moment itself is quite specific), which if present would be important for selecting down to a single or plausible few narratives, causes (or allows) us to consider all sorts of stories. This short story is not just one narrative. It is many.

But it is not every imaginable narrative if I limit myself to plausible cause-and-effect chains. Further, the list becomes even shorter if my standard is likely chains. I file through various possibilities in my mind, instinctively following basic narrative rules relying on an unspoken contract between the writer and reader: that the cause-and-effect chains will more or less make sense based on the rules of the genre, and the widely held *worldviews of physics and psychology as represented in narratives (because we know to suspend strict rules of physics and such for the purposes of the fictional world), even if there are some surprises along the way. I also know that, if the context is not stated (as is the case in this example) then I should probably deploy likely, “normal” contexts rather than outrageous ones such as “these are the shoes of an android only thought to have been a baby.” Were my literary critical posture to be grounded in a view of the text as separated from the author and its initial cultural context, I can make whatever interpretation seems intriguing. But since, as a class, we are using narratives to explore cultural milieu, we are committed to imagining the author or director’s cultural contexts and those of the intended audience. This is the basic interpretive posture for the *course method (and is also the usual posture of the casual reader and viewer). I just think it is good to note at least once that this is not the required posture of many literary critical approaches.

Given these basic rules for narrative context and narrative progress, I think many would accept this as a plausible narrative built from our short sentence: “A couple was looking forward to their child’s birth but something happened and the baby died. In despair (and perhaps in poverty), the grieving parents decided to sell the shoes.” Statistically speaking, I think it is unlikely that this was the narrative you created but I also think you are likely to be willing to accept mine as a plausible option. However, similarly, I believe few of you would be comfortable with this: “A professor stole a parents’ newly bought baby shoes and put them up for sale on the black market.” It is not that this is outside the realm of possibilities but rather it seems somehow pointless (implausible), and based on unlikely contexts. That being said, if the sentence were not stand-alone but rather part of a longer work, one with a dystopian *worldview proffering a theme of the callous, selfish behavior of its inhabitants, now the narrative just offered is indeed plausible enough to deserve consideration.

Please read the following invented initial lines of a short story and continue the narrative in your mind: “Early in the Ming dynasty there lived in a lovely and elegant estate a beautiful young lady. That year, the new magistrate of the province moved into the grand estate of the previous magistrate, together with his wife and intelligent, handsome son.”

In extending the narrative, I am guessing that many of you, especially those of you who have seen a great deal of East Asian TV drama, have already probably decided that the narrative will be about the man and woman, and that they will eventually get together although there might be some challenges along the way. If so, you have (probably automatically and unconsciously) deployed as a reading hypothesis a common narrative *model already learned elsewhere: the “talented man will get beautiful girl” plotline. This *scholar-beauty (caizi-jiaren) storyline was particularly common, almost cliché, in China’s Ming dynasty (14th-17th centuries) love stories. We encounter it everywhere in our analytic work for this course, sometimes just as it is and sometimes as a baseline from which a narrative deviates.

Here is another narrative fragment to complete: “I once had a boyfriend who, whenever he would come to pick me up, would say, ‘Here’s Johnny!'” Do you think this the first line of a happy, young-romance story about a cheerful young man? Or, rather, do you think it might be the first line of a horror film? Your choice will turn on whether you know about the film script line “Here’s Johnny” and whether you think knowing that is plausibly relevant or not. In this case, your interpretation turns on whether you build the narrative (or not) based on what might be (but might not be!) essential inter-film contextual information.

How quickly do we decide plausible contexts? Usually it is during the realtime exposure to the code. Often it is reconsidered and refashioned after consuming the code (after finishing viewing the film and thinking about it). Here is an exercise using a film trailer that might indicate at what point you decided you had gathered enough contextual information to settle on a plausible narrative. The film title is removed, since it would give away the context. (The title is in a footnote if you want to check it after the exercise.)

View the clip while at the same time trying to correctly answer this plot outcome question: “What will likely happen between these two?” Watch yourself as you build a hypothesis of narrative outcome. What are you relying on to give a good reason for your narrative? As the clip provides more and more information, how quickly are you readjusting your possible plausible narratives? When do you arrive at an answer that you are comfortable with? (If you want, you can stop and note the timestamp of that moment.) When did you arrive at the “correct” answer? Or, do you never get to that answer? Think back: What did you do or not do, know or not know? I hope this is an opportunity for you to learn something about how you, personally, approach building narratives.

Here’s the link to the clip. (This clip, by the way, is not on the multimedia list at the beginning of this book or part of the bibliography at the end.)

Finally, similar to the baby shoes example, I would like to offer another very short set of words that generates a large narrative, in this case a 18th-century Japanese poem by Yosa Buson:

They changed the wardrobe to spring clothes —

this couple once sentenced to death

This is a powerful narrative but inaccessible to many because the cultural information is not widely known. At this time in Japan couples who had committed adultery were both sentenced to death. Couples in such situations sometimes ran away (indeed, were sometimes allowed to run away). This couple has done so. Now it is spring. They are living together in hiding somewhere. As is the usual custom of any household at that time, once spring comes the winter clothes are stored away and the spring / summer clothes are brought out of storage, to be placed in the drawers and such for ready access. This simple act is not at all ordinary for a couple who had expected death, for a couple so in love they had taken the risk of death to be together. They are now safe, but perhaps not. They could still be discovered.

In this way, we complete narratives following a wide range of guidelines: how people usually behave, the expectations of a particular genre (for example, in horror films when someone evil dies we are half-expecting him/her/it to jump up again—death in horror films does not necessarily come easily), the mood of the story (for example, if my above story has started instead “Early in the Ming dynasty there lived in a lonely and dark estate a beautiful young lady…”), our own personal interests, and, yes, cultural information. We are constantly “running” (simulating) cause-and-effect chains in our mind as we read, generating stories by identifying how Event or State B relates to the preceding Event or State A.

14.2.2.2. “Making sense” of narrative progress: The logics of getting from Event A to Event B

When my brain interprets information, it first tries to match that information to known patterns. This is fast, efficient, and fully sufficient in most situations. We have discussed this in terms of *attractors and *models. This matching is essential for completing *narratives, too. We use matching processes to build the worlds, people, and events that we find in narrative. Our reading sense that “we know that person will die” or “we are sure this will turn out okay” comes from how we have matched the current stories to our previous reading experiences, at all types of levels.

Our challenge when reading cross-culturally is that the brain is strongly inclined to match rather than revise or build and does this automatically without notice. And, in a practical sense, this is going to be just fine even if we bumble around a bit. But for this course we are emphasizing the other end of the spectrum. Our task, instead, is to revise as frequently as seems necessary in order to achieve a best understanding of cultural differences large and small.

The ability to suspend the urge to match and instead engage in the greater effort of revision and construction is a skill set that does not come easily. I have found at least one practical way of helping one notice when the model is not quite close enough is when *narrative progress seems out of sorts for some reason. In other words, when it does not “*make sense” to us. Of course, sometimes this is just subpar story-writing by the author or director. Of course, sometimes it is because the nature of that type of narrative is to be disconnected and puzzling. But for the most part we assume that most *narratives, most of the time, have their meaning determined by a collection of *worldviews and *values shared with the culture of the target audiences. If the story moves from one event to another in a way that does not plausibly “*make sense” to you, it is possible that there is a *worldview in play of which you have no knowledge or which has not occurred to you, or a missing *value from the array of *values you have considered, or simply a different hierarchy of *values.

This, then, will always be our start point: “making sense” of a person’s thoughts, feelings, or actions, and the way a narrative moves forward as best we can by assuming the *worldviews and *values of the target audience. Dialogue within class and among team members around these issues is a good way to notice cultural differences, to get past “*horizons of expectation.”

For the purposes of this course, I would like to posit that, for commercial reasons, most films are indeed familiar-feeling in the progress of their stories. Put another way, it is the premise of this course that audiences prefer films with familiar *worldviews and *values and eschew films that mount fundamental challenges to their way of thinking about the world through the film’s difference, strangeness, or sincere rejection of the culture’s *worldviews or *values (which of course is sometime exactly, and wonderfully, the project of art in contrast to purely commercial endeavors). Additionally, theater-going viewers (an important first-time audience for films) must consume the film’s story in realtime without pause or a chance to repeat (reread) a segment, and most of these viewers would, frankly, prefer not to work hard in the process. They want to enjoy the film, not feel tired by the end of it. Therefore, storylines that cannot be easily consumed because of unfamiliar *worldviews or *values are at risk of becoming box office disasters, even if critically acclaimed. There are, of course, exceptions to this standard movie-making approach. With that in mind, the films selected to be viewed in this class are—for the most part and quite intentionally—films that had a large budget when produced and were therefore required to appeal to a large audience once released. This situation forces the director (and others involved in production) to fashion the film to have at least a somewhat broad appeal, that is, understand and work comfortably with the *worldviews and *values of its target audiences.

This “making sense” of a *narrative is a key component of the course’s interpretive method. The premise is that when some content of a *narrative, and in particular the cause-and-effect link between Event A and Event B, seems difficult to understand, the “puzzle” presented suggests that there might be something missing in our array of *worldviews and *values, since the premise is that the *narrative will, whenever possible, “make sense” to the *model viewer, that is, one who can deploy *worldviews and * ethical values that closely match those that the director and others would hope would be used for understanding the film. This “something missing” is an indication that we have matched the event to an inappropriate *model and need to revise or build a new *model. Normally, when consuming a *narrative, we would just ignore these *bumps along the way. I ask in this course that you notice them, ponder them, and seek to remove them where possible via a contemplation of the possible *worldviews or *values that might plausibly be present.

14.2.2.3. Bumps in the road—What are plausible logics that support narrative progress (cause-and-effect chains)?

What happens when the process does not go well, when we lose a sense as to what is happening or why it is happening, when our idea of what has just happened does not match well with others when we “explain” the story (offer our cause-and-effect reasoning and thus also our conclusions as to what happened)? In practice, usually we just move on and do not worry about the *bump in the road. It if gets too bumpy, we stop reading or viewing and are more or less “done with that.”

In this course we see these *bumps as opportunities. We first start with the premise that the narrative does indeed make sense to someone (that is, it is not a failure on the side of the writer / director, although it may well be, in truth). Then, our task is to try to puzzle our way through, checking to see whether we, or the people we are talking to, are missing cultural contextual information that adjusts the interpretation to within the range of what plausibly “makes sense” without just reinventing it to match our world. Good stories engage in interesting ambiguities and have tensions among possible meanings. It may be that is what is going on. But it may not be. It might be there is no real ambiguity, just lack of cultural understanding. We try to determine which it is. This is difficult, but it is what we do.

Bumpy roads as a result of unfamiliar *worldviews. Over the years I have taught this course, resulting in the analysis of dozens of films, I have noticed that the range of *worldviews in recent films does not differ greatly, that there seems to be something close to a universal language in the global film industry in terms of *worldviews. (I do notice more country-to-country *worldview differences in early films, say from the 1960s or before.) *Worldviews make expansive, authoritative claims on how the world works, so when the *worldview of the viewer does not match that of the film, the disconnect is distinct and the film probably seems too distant and irrelevant to bother with unless it has other saving features. Viewers, even cross-culturally, can be quite willing to amend worldviews when necessary. For example, East Asian martial arts films, with their impossibly long flying leaps, strike the uninformed viewer as absurd (implausible according to the laws of physics) until that viewer “learns” (accepts) the physics of the genre. Once the genre rule is learned, plausibility returns and the *worldviews are back in alignment—comfort is restored (the *bump is smoothed out) with the new law of physics being, “no one can leap in slow-motion through the sky for long distances unless you happen to be a martial arts master, then you can, so let’s stop worrying about that and enjoy the film.”

Bumpy roads having to do with *ethical values. Unlike *worldviews these differences are everywhere. Some *values are unknown, while others that the viewer thinks are important are treated lightly, while still others that the viewer thinks are not important seem to have exaggerated presence. Sorting out the *values is very much an exercise in understanding the texture of the cultural context. But we should note that this “cultural context” is not just simply an extension of realworld *values. It is the *values the audience is willing to embrace as a member of a realworld cultural group plus a member of a filmworld cultural group. If one takes as the sole source of *values one’s realworld *values when watching a horror film, there is simply too much death and destruction to accept comfortably. However, if one says, “Well, yes, that is certainly quite a few dead people in the last five minutes but, hey, this is how it works in the world of horror films,” one has semi-suspended one’s realworld *values for a different set. When one can no longer do this (perhaps the film has become too “realistic” or you are simply the type who is uncomfortable in adopting horror film viewer *values) the discomfort level, the *bumps, become quite sharp and distracting.

With the above in mind, I would like to make the below few observations with regard to areas where Western viewers of East Asian films sometimes experience *bumps, according to my experience of teaching this course:

Cause-and-effect chains that include, as a plausible cause, the idea of “retribution” are not uncommon in East Asian films because of the influence of Buddhism and its theory of karma. In its pure teaching karma does not mean if I do something bad now something bad will happen to me later. However, it offered this formulation as a way to offer an ethical teaching and has been widely embraced and remains an active *fragment in East Asian cultures at a general and sometimes active level. “Retribution” and “paying for one’s sins” and “God’s judgment” are also Judeo-Christian principles, so there is not a great deal of dissonance felt by the culturally Western, East Asian film viewer. But where the interpretation gets off track is that “punishment” in East Asian films is not the result of original sin or sinful acts, but rather an impersonal law of metaphysics. The impersonal and unchangeable nature of karmic law is, I would suggest, one reason “confession” plays a less important rule in East Asian narratives as a cause that could neutralize a cause-and-effect chain where bad action invites painful event. There is no God who can forgive and relieve one of the approaching results (karmic punishment or retribution) of a bad act. This “missing confession moment” or diminished weight placed on the value “one should forgive” sometimes puzzles Western viewers.

Cause-and-effect chains that show a high degree of instability are part of the *worldviews of both Daoism and Buddhism. No state is permanent. Change is everywhere in the air. These are typical aspects of the *worldviews of East Asian films. If that change seems to be one that is causing suffering, or will, then it is also drawing on the Buddhist teaching that we experience change as suffering (the second Noble Truth of Buddhism). Movie viewers with Western worldviews that uphold linearity as a truth—that things can move towards the good or the bad but, once arrived, can stay that way—sometimes show an impatience with the “round and round” feeling of East Asian narratives that are more cyclic in their view of how the cosmos works.

Fate and free-will. Western morality places a high degree of emphasis on choice as a way to morally judge an individual’s actions. Plato’s chariot allegory from Phaedrus and the Biblical story of Adam and Eve make this quite clear and this is born out endlessly in the progress of Western narratives where courage and sufficient will-power to do the right thing are viewed as moral assets. This view, actually, does not sit well with worldviews that place the human into the natural world as one element of it rather than a special, semi-divine entity meant to rise above the natural world. All East Asian ways of thinking view man as between heaven and earth but that these three are all part of a single cosmos with a single set of universal principles. This subverts the special qualities of individual acts of free will. Instead of being viewed as godly progress towards individuation, or “owning” one’s actions, are any number of other ways of thinking about this, acts of free will can seem uncooperative and uninformed about the nature of the current state of affairs. In the same vein, bending to the conditions of a situation can be viewed as passive from a Western perspective but an intelligent recognition of the power of fate from an East Asian perspective. That a given situation includes factors beyond one’s control and to which one should harmonize or submit fit well across the spectrum of East Asian *authoritative thought systems: Daoism argues for the correlation of factors so the nature of a given condition has broad influence on the course of all events, Buddhism argues for karma as predetermining outcomes, Confucianism places value on social harmony asking the individual to submit to authority and larger social needs.

Most Western films subscribe to a post-Freudian view that is in fact naively hydraulic and not supported by current science but still widely embraced because it matches so well with subjective feeling: an emotion builds up, the person feeling the emotion finally explodes thus releasing the internal pressure of that stress or emotion, and this explosion is in a sense healthy by returning the psyche to some sense of equilibrium. This type of explosion is viewed less positively in East Asian narratives that are less steeped in a post-Freudian world. Explosions are often viewed as a failure of maturity or a disruption of social harmony rather than a healthy release of pent-up tension. Put in the language of cause-and-effect, East Asian narratives recognize this as a cause for actions (result, effect) but are somewhat less likely to consider it a forgivable cause for the effect.

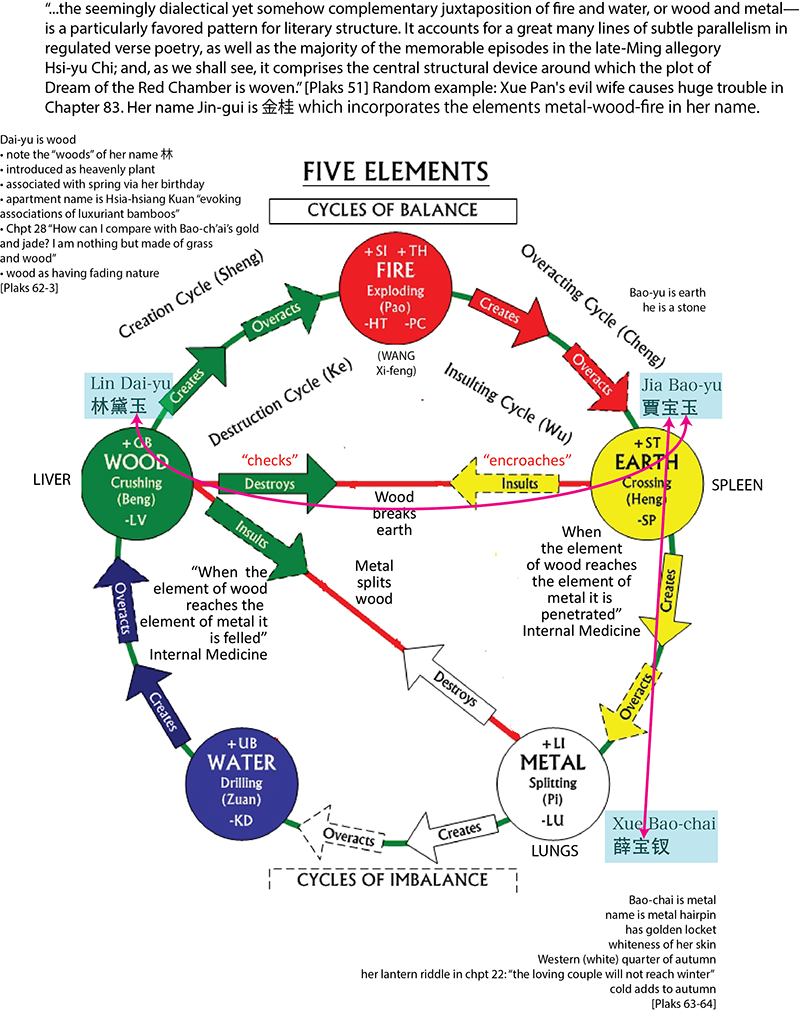

Predicting personality types and how specific people will interact. Blood type is not important in the West as a predictor of personality or successful partner combinations but it is very popular in Japan and attracts some interest in South Korea and Taiwan. From our perspective, as we look for “causes” for actions, or relationships, perhaps we should keep in mind that blood type might be somewhere in the background, that the narrative figures are displaying stereotypical features of certain blood types, and the director expects the audience to factor this in. Cosmological factors such as zodiac signs or the year in which one is born, or the current year on the 60-year calendar (“Stems-and-Branches”) might also be at play as causes. These are probably not major factors in most cases (although at least Japanese anime sometimes leans heavily on these types of things) but they are good examples of worldviews that are sometimes more powerful in the fictional world or a filmworld than the realworld. Story of the Stone perhaps deploys ingeniously a Daoist cause-and-effect world based on the five elements (wuxing). At least this is the credible assertion put forth by a scholar who analyzed the medicines, symptoms, and doctor’s diagnosis of the novel’s three main narrative figures Daiyu, Baoyu, and Baochai who form something of a love triangle.[10] His argument offers a different cause-and-effect set than what reader’s might ordinarily deploy. Below is a graphic representation of how he views the relationship among the three figures. While this will make the most sense to those who know this novel well and something about the five elements, it is nevertheless for anyone a dramatic, premodern example of a departure from contemporary worldviews and their support of cause-and-effect chains:

16.3. Film narratives as objects of analysis

Given the nature of the course’s analytic method, we take various film content as our primary objects of interpretation. As works of art and works of entertainment, films can be delightful to work with, but it is not for these reasons that they are at the center of the course. This is not a course in film study or film appreciation. Instead, we practice interpretation of narratives based on our understanding of the *cultural contexts provided by *worldviews, *ethical values, and *common practices. It is for their interpretive potential that they are the focus of the course.

Film’s rich multimedia aspects—music, cinematography, fashion, body language, tone of voice, expression, and so on—all can help toward an interpretation. Further, most films also need to deliver and complete a plot within a specific, relatively short, period of time. The steps in plot development and plot outcome are, again, exceptionally useful to us when trying to reconstruct *worldviews, *ethical values, and *common practices, and estimate their *status.

This requirement—to “tell a story” in a short period of time without affording the reader or viewer the opportunity to pause or reread (re-consume)—as well as the general tendency for films to honor affective content over cognitive complexity, bring tremendous pressure to bear on the film’s creators to simplify themes and other content. Most films are meant to be more or less consumed in realtime without a lot of audience effort, as they stream on the screen. Narrative structure will be fairly straightforward, unlike some written works. Given the already complex nature of our topic, these simplifications can be helpful.

Film is collaborative. A film’s message and impact ultimately is a meta-effect after the soundtrack and musical score have been added, the visual effects completed, the extensive editing approved, and so on. Often hundreds or thousands of individuals contribute to the final product. The viewer, immersed in this wash of information, will be heavily influenced toward certain interpretations to what she or he is seeing, but this very collaborative complexity also “opens” the film through its contradictoriness and tendency to evoke rather than state. In these gaps and suggestive spaces, the viewer’s own *worldviews, *ethical values, and sense of *common practices can heavily guide interpretation. This is, perhaps, one of the reasons films feel “intimate”—a story we can relate to—because they are designed to be broadly appealing by being open to our *values.

It is true that the reality of a film’s collaborative origins will complicate things for us as we try to sort out all the various *worldviews and *values that might be in play. Because of their commercial concerns, films, I would suggest, are more or less committed to reflecting the *values of the audiences they seek to gain. (Box Office Mojo provides ticket sales information for most of the movies we view, both domestic and international data. If we accept my assumption that audience size is determined in part by how familiar the *worldview and *values of the film are to the audience, the following numbers, for example, become interesting: Dolls (Doruzu, 2002), one film often viewed in this course, grossed $4,067 in the United States, $886,615 in France, and $4,123,035 in Japan.) Some directors are more interested in pulling everything tightly together so that it all works under a single vision. Others just allow a range of content for “effect,” intuitively (or strategically) doing so to appeal to a range of audience types.

While the complexities of film’s collaborative origins and the split and its uneven allegiances to artistic vision and commercial success make our investigations dauntingly complex and our conclusions tentative, there are also two potential advantages. First, when everyone seems aligned behind a certain *value that in-and-of-itself is a fairly strong indication of its *status. Second, the messiness of films mimics the messiness of our real-world, multicultural situations that we wish to navigate. Interpreting films and sorting out our own situations are, of course, different in many ways, but in the layered, contradictory, and complex nature of films, we are not so far from the conditions of our real-world interpretive imperatives.

The *course method allows interpretations of love narratives in films in four areas: what a film means to us personally, what we think the director might be trying to say about love, how various audiences might appropriate its content, and the constructed world internal to the film itself. All of these are excellent opportunities to explore *worldviews, *values, and *common practices through the construction of *ToM. We can concern ourselves with trying to reconstruct *worldviews and *values of the director, the audience, or the fictional characters within the narrative. Any of these paths is potentially rich in terms of sharing interpretations. All we must do is agree to look at the same area: personal reaction, director, audience, or fictional characters. The essence of this course is the collective attempt to construct a specific *ToM or set of possible *ToMs through appropriately applying our outside knowledge of film’s cultural context and leveraging the full range of information offered by the film itself.

I have situated this work within narratives to give us a controlled space to discover our differences and, if lucky, something about the roots of why we think as we do. We could, in theory, just sit down facing each other and share our opinions of love, but such discussions will lack productive focus. By introducing a common object that we all interpret, we anchor our opinions on something, thus making them accessible to one another for close consideration and comment. But this is also where my study in Buddhist psychology intersects with my interest in the functional *status of narrative. Bluntly put, I think one’s identity is a complex, contradictory, puzzling but somehow more-or-less functional web or temporary assembly of narratives that one tells oneself over and over. Intimate relationships start a “history” and that, too, is a powerful set of narratives: how one thinks of the relationship, how the other thinks of it, a “shared” view of it, and how many others view it. Private thoughts such as “You and me are like star-crossed lovers” or “I have discovered my soulmate” import into a unique relationship between two specific people a narrative idea on how to view the relationship. These narratives already exist, embedded in and supported by a culture. Who “we” are as a couple is grounded in visions of what couples are that are upheld by some, or many, others. In other words, the boundaries between who “I” am, who “we” are, and what culture thinks “I” am and “we” are is oh-so-porous—even dangerously so.[11] Because this is how I view the formation of the self and identity, it is then obvious that I think an understanding of *cultural context and its dynamic relationship to an individual is absolutely key to ferreting out our different ways of thinking.

- David Landis Barnhill, trans., Basho's Journey: The Literary Prose of Matsuo Basho (State University of New York Press, 2005), 14. ProQuest Ebook Central. ↵

- "Theory of Mind," Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy IEP, accessed December 27, 2017, http://www.iep.utm.edu/theomind/#H3 . ↵

- Julia Kristeva, New Maladies of the Soul, translated by Ross Guberman (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), 9. ↵

- Li-young Lee, "The Mood from Any Window," in Book of My Nights, American Poets Continuum Series, 68 (Rochester: BOA Editions, Ltd., 2001), Kindle Edition. ↵

- Chikamatsu Monzaemon, "Chikamatsu on the Art of the Puppet Stage," in Anthology of Japanese Literature, from the Earliest Era to the Mid-Nineteenth Century, ed. and trans. Donald Keene (New York: Grove Press, 1955), 389. ↵

- Ryosuke Ohasi, "The Hermeneutic Approach to Japanese Modernity: 'Art-Way,' 'iki' and 'Cut-Continuance'," in Japanese hermeneutics: current debates on aesthetics and interpretation, ed. Michael F. Marra (University of Hawai'i Press, 2002), 29. ↵

- See, Umberto Eco, Interpretation and Overinterpretation, Cambridge University Press, 1992. ↵

- Sometimes attributed to Ernest Hemingway. ↵

- This is an edited trailer from William Shakespeare's Romeo + Juliet (1996, Los Angeles). ↵

- Chi-hung Yim, "The 'Deficiency of Yin in the Liver': Dai-yu's Malady and Fubi in "Dream of the Red Chamber," Chinese Literature: Essays, Articles, Reviews (CLEAR) 22 (Dec., 2000): 85-111, doi:10.2307/3109444. ↵

- This basic position, for me, comes from Jacques Lacan's theory of how we derive identity. Lacan was a mid-20th century French psychiatrist and critical thinker who extended and altered some of Freud's standard theory of the self. It isn't possible to summarize in a footnote his complex view of the origins of self, but I feel compelled to at least note that it is a more complicated process than what I suggest in the statement just made because, while we "appropriate" narratives from others to give substance to our identity, these appropriations are actually mirrorings of our own desire, and since everyone is similarly constructing identity with the same process, everyone one is, in essence, mirroring everyone else. This transforms "narrative" into an ephemeral but on-going process among members of a culture, not a static object—although, because of its persistence, it exerts influence as if an object of substance. We will leave aside this more nuanced treatments of narrative and treat them as cultural "objects," but I want to be on record here that this is a simplification of the state of affairs in order to serve the practical needs of the course. ↵