Introducing instances of cultural contexts via 5 Centimeters Per Second ◆ resources for interpretation ◆ worldviews ◆ ethical values ◆ common practices ◆ situational factors

Key terms and concepts introduced in this chapter:

- cultural contexts

- ethical values (values)

- common practices

- instance

- mixture and mixing

- situational factors

- worldviews (cosmic and social)

Key terms and concepts mentioned in this chapter that should now be familiar:

- horizon of expectation

13.1. Overview: Cultural contexts as worldviews, ethical values, and common practices

13.1.1. The central interpretive question of the course

What *cultural contexts might be relevant to a person’s actions, thoughts, or feelings? This is the fundamental question of this course. We begin with the premise that we want to know, with as much cultural accuracy as is credibly possible, a range of plausible answers to this question.

Much of the time this is not difficult to answer. If a person smiles after taking a bite of something, our first interpretive guess is that the food tasted good. In practical situations, this will usually be enough of an answer. However, we are using situations as interpretive opportunities to explore further. There may or may not be something more to consider, but our task is to find out one way or the other.

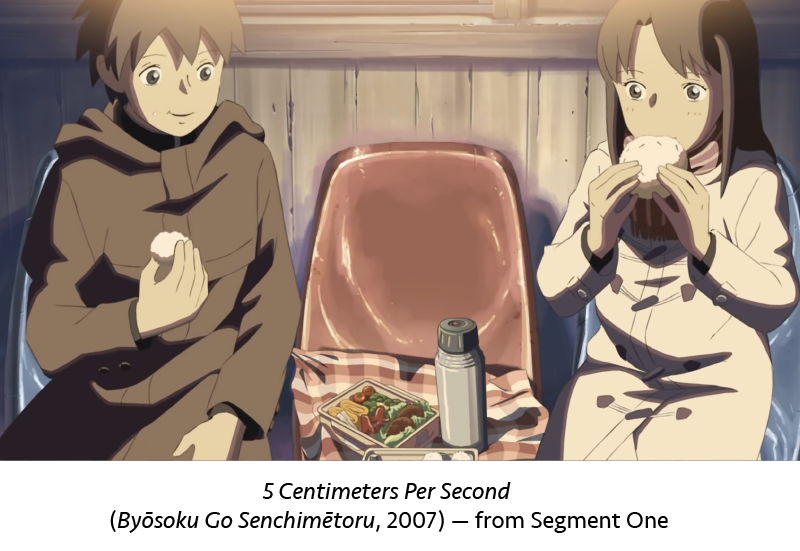

13.1.2. Interpreting an instance in 5 Centimeters Per Second

In the Japanese film 5 Centimeters Per Second (Byosoku go senchimetoru, 2007) there is a scene in the first segment where a boy and girl eat together a box lunch that the girl has made for them so he can have something to eat when he arrives at the train station. He arrives late. They briefly talk and then she offers him the box lunch.

Let us take the following as the *instance we will analyze, the situation that offers us an opportunity for interpretation:

“What is the boy thinking while he is chewing on the riceball she made for him?”

A moment from the scene looks like this:

We can collect a large amount of useful contextual information relatively easily from the story itself and how it is presented.

- In terms of narrative (story) development, the boy has arrived very late to a cold train station in the dead of winter. He has traveled far (and with considerable nervousness because he has never traveled alone before) to see his school girlfriend. He is so late that he does not expect her to be waiting for him still, or half believes she will not, but there she is.

- The setting also contributes to our interpretation—a train station so late at night that no one else is there. While it is true that it is a cold and empty room at this point, train station waiting rooms are very familiar to Japanese and there is some additional sense of comfort from the familiarity of the setting. That it is late and no one else is waiting for a train helps provides an intimate environment for their time together. (There is also a fatherly train station master within viewing range of them who serves as a counterpoint to their young age.)

- The music is thoughtful and a little sad while the dialogue is somewhat sparse and tentative (slightly formal) but gentle:

Sharing riceballs—sound file from 5 Centimeters Per Second

- The body-positioning of the two is significant. They are not turned toward each other but are definitely “together” in their seats as they both face forward while fully aware of the other. There seems to be harmony between them.

We can also think of the director and consider what her or his artistic vision might be. In this case we come across very useful information. The director is Makoto Shinkai, who also directed the commercially successful (in Japan) animated film Your Name (Kimi no na ha, 2016). That film explores the challenges of two young people who love each other and are looking for a way to be together. The film is heart-breaking and rather pessimistic. If we return to our box lunch scene we can now reinterpret this as possibly that the boy is “happy for the moment but aware that they will need to say good-bye again very soon and will live far apart from one another.” This, of course, would be an extension based on the assumption that the director upholds a certain view across his various works. The style and content of the two films would suggest this but it should probably be further checked if we plan on relying on this other film.

Most of the above conclusions do not require Japan-specific cultural knowledge for reasonably good accuracy. The *model narrative is familiar, namely, “love stories are often about the difficulties of two who care for one another but are prevented from being together for some reason.” The affective components (pace, “camera” angle, the emotional feel of the music, the sense evoked by the visual look of the scene, the qualities of the speaking voices, and the body language) are also not very culturally specific although that the two youth are not looking at one another directly might be misinterpreted by some not familiar with Asian body language as somewhat odd or unfriendly or indicative of tension.

Although with the contextual information so far I think we have already arrived at a sufficiently powerful interpretation of the boy’s thoughts and feelings, our goal in this course is not that. Understanding the basics of the story is just the first step. We are using the scene as an interpretive opportunity to explore *cultural contexts which I have defined, for the purposes of our method (rather than some theoretical position) as representations of *worldviews, *ethical values, and *common practices. (In this course we focus on the first two of these. In real world situations the third is of course equally important to understand if one is to operate comfortably or effectively in any given cultural environment.)

So let us continue exploring the *instance, keeping in mind our conclusions up to now.

If we look carefully at the contents of the box lunch, and if we know something of Japanese culture, we see that: 1) it has been made with great care, and, 2) it is full of all the favorite things that someone like the boy would like. In short, it has been put together with considerable attention and thoughtfulness. We should take this as representing the girl’s love for the boy since there is a cultural *model of Japanese women waking up early every morning to carefully make box lunches for their children and husband. These children and husband then open their boxes at lunchtime, see the careful work, and feel the love that it evidences. Further, we can conclude that the boy will be thinking this as well, and that the girl knows he will think this. In the scene he confirms it, as he should. When she asks how it tastes, he answers that it is the best thing he has ever eaten. The box lunch and the boy’s response can both be credibly interpreted as confessions or confirmations of *love.

Of course, we already know that they love each other—nothing in the film so far has suggested that this is about one-sided love, lukewarm crushes, or anything like that. We are not trying to prove that point. Instead, what does this *instance suggest of how the film defines love? I would like to suggest that there are numerous Japanese *values about love that are being affirmed in this capping-moment scene:

- Love is the thoughtful and attentive consideration of another’s needs supported by careful actions to serve those needs (the making of the delicious box lunch, one he would truly enjoy).

- Love is nurturing or perhaps more specifically when a girl nurtures (box lunch making) while a boy shows happiness and appreciation for the nurturing (box lunch eating).

- Love is to sacrifice for the other and is enabled when one has the courage to do so (he takes on the frightening challenge of the train trip, she sits for hours at a cold train station).

- Love is being trustworthy (he never gives up finding a way to get to the train station, as promised; she waits no matter how long, as promised).

The above obviously are not exclusively “Japanese” *ethical values. Our considerations of culture will indeed usually end up with this type of destination, that is, not necessarily the discovery or deployment of different *values but rather concluding that there needs to be different emphasis among possible *values.

For example, it seems that if this were a Western film about high school love rather than a Japanese anime borrowing from the genre of “pure love” (jun-ai 純愛) films, the first thing these two would do when they finally meet is at least hug and probably kiss. But in this scene, eating together is their way of hugging hello. We should not decide that they care any less for each other because they have not hugged. One reason is that physical contact is less common among “typical” Japanese and this film wants a universal quality to it (this story about this boy and girl is really a story about every boy and girl) so the waiting scene is common (almost cliché), the making and eating of a box lunch is common (and also cliché),[1] even the body language of the two also indicates “these are typical examples of a good, innocent boy and a good, innocent girl” who are learning slowly the first steps of love. Another reason is that the film wants to separate physical attraction from feelings of the heart. Western narratives are more inclined to treat these as two sides of the same coin: feelings of friendship or love will naturally find expression in hugs and kisses.

Ultimately, interpretation draws on a complex calculation of a vast array of things. This is my interpretation of the scene:

The boy is holding back the essential loneliness of life for a brief happy moment with the girl he loves. His heart is full to bursting with the painful contradiction of two facts: he can be with her now but soon will be separated from her. Yet, being young, these painful feelings are strong but still somehow vague. He is learning about life.

I have deployed a wide variety of experiences:

- that I have seen this film several times and discussed it with students for several years,

- that I have also seen the director’s other film Your Name,

- that I have lived in Japan numerous times and been married for many years to a Japanese woman,

- that I speak the language,

- that I study literature of love in this and other countries but especially Japan from 9th to 21st centuries

and predispositions:

- that I tend to view things darkly.

13.1.3. Resources for interpretation

Generally speaking, a reader’s or viewer’s interpretation of a narrative moment arises out of complex (and mostly unconsidered) tensions among his or her own *worldviews, *values, and many other things including what can be imagined are the *worldviews and *values of the *narrative figures themselves and/or the author/director of the work. “Other things” include, in fact, an exceptionally large number of factors. For example, we could add to the above list the narrative situation, memories of similar events in our own lives, genre expectations, and so on. For any interpretation, the reader or viewer quickly gather contexts from a wide range of sources, sorts through them, decides what she or he thinks is a good mix of factors to weigh, then makes interpretive conclusions. This process happens rapidly, naturally, even easily.

What this course attempts to do is build an interpretation more slowly and with greater care so as to collect better contexts and apply them more critically. Through directed study and lively discussion with others in the room, we extend the range of contexts we can consider (press against the “horizon of expectation”). We manage the application of the plethora of possible contexts through the *course method.

I am deploying in the case of the box lunch scene a certain Japanese *worldview (one with which I do not agree by the way) that I have encountered frequently in the literature of that country, and definitely in Your Name:

This world is not a place that supports love. People who are in love are usually separated by circumstances. If we want to think about, talk about, or experience the most authentic feeling of love, it is best described negatively, that is, in the moments of yearning when lovers are apart.

This view, I would suggest, bears down on our box lunch eating scene heavily, making it (and the whole film for that matter) heartbreaking.

While this course is not just about arriving at an interpretation but being able to identify to some degree the factors involved in that effort, we are not trying to do everything. We ask only the specific question of What *worldview, *values, and *common practices seem relevant to consider and to what degree might they be in play. And, since we analyze *instances, which are narrowly defined areas at which to point our interpretive energy (in this case, the boy’s thoughts over a few seconds of time), we are rescued from some of the seeming endlessness of the analysis.

Again, if this were a film studies class and our project was to bring out the details of the scene, a very good interpretation of the boy at this moment would be:

The boy is happy to finally see the girl. His heart is joyful that she waited and that she made lunch for him, both indications of her love. He expresses his own love for her in delightfully eating her food and his gentle speech. However, he also feels somehow the bitter-sweetness of the moment.

However, we have looked past that (but kept the conclusions at hand), to ask the more culturally specific questions: “What are some of the ways that love is expressed, given, and received between members of a Japanese subculture (Japanese high school students in private) in a case like this?” and “What is the *worldview that hovers around the story at this point, and is it generic or somehow specifically Japanese in content?”

13.2. Cultural contexts and worldviews (cosmic and social)

13.2.1. Defining “worldview”

The English word “worldview” is ill-defined and loosely used. Thank goodness for the flexibility of language. It is what gives it expressive power. However, for the purposes of this course, we need a working definition:

Worldviews are assertions or notions of how the world works. A worldview might assert something about how the Universe itself works (cosmic worldviews) or more specifically about the makeup of human nature or how people will behave (social worldviews).

An example of a *cosmic worldview would be the Buddhist *principle that everything in the Universe, without exception, changes. It is the first of the four Noble Truths: “This conditioned world is characterized by dukkha (impermanence).” (This is also a Daoist assertion, but one based on entirely different reasoning.) Another example would be the Christian view that God, who is all powerful, has the ability to forgive and cleanse someone through that individual’s sincere act of confession (“My God, I am sorry for my sins with all my heart. …”).

An example of a *social worldview about human nature would be the claim by the Chinese ancient philosopher Mozi: “Supposing people see a child fall into a well — they all have a heart-mind that is shocked and sympathetic.”[2] Mozi is making a claim about human nature, “how people are.” Another later Chinese philosopher, Xunzi, challenges this with an entirely different *social worldview: “People’s nature is bad. Their goodness is a matter of deliberate effort. Now people’s nature is such that they are born with a fondness for profit in them.”[3]

If someone says in a film “Doesn’t everyone cheat?” she or he might be simply making a statement based on observations, in which case that person is claiming that the behavior is *common practice for the cultural group to which she or he belongs. (We will discuss *common practice later.) On the other hand, that narrative figure might be asserting something about the very nature of our social selves—that all humans are evasive and duplicitous.

13.2.2. Why we care about worldviews

Our interest in *worldviews is in part because of their powerful universal, unchallenged presence across a culture in its many situations, on the one hand, and, on the other, because their early association with a culture buries them deep within it, to generate thereby all sorts of cultural elements.

For example, we might be able to say that people sometimes cheat and some more than other, but we cannot challenge the Buddhist *worldview of impermanence with such a “sometimes” description, that is, we cannot say “things sometimes change and sometimes do not” without rejecting the very premise of the *worldview. In this way, the *principles within the accepted *worldviews of a culture are very firm. Their consistent presence in a wide variety of situations can have a large impact in shaping our thoughts, feelings, and actions.

Worldviews are universally present, in part, because many of them developed together with the inception of a culture and are indeed part of what makes a culture what it is. While I accept the postmodern, posthistorical claims of many post-1960s theories that we are in a new zone so to speak where “organically whole” theories and traditional influences have lost their grip, I do take as a premise for this course that history matters and that early cultural positions have diffused throughout the membership, to be handed down over the generations in some form or another.

It is not that modern Chinese, for example, are Daoists, but learning some of the propositions of Daoism, I would suggest, will indeed provide a vocabulary for identifying aspects of Chinese culture. For example, social harmony, balance, and patience are all Chinese cultural ideals. Traditional Chinese medicine is based on the *cosmic worldview of harmonious balance among the various parts of the body, a *worldview that is distinctly Daoist in origin. Few will say, “Be a good Daoist and drink your tea because the yin qualities of the tea will cool your fever.” Instead, now, there is probably not much conscious content of the *worldview beyond the simple suggestion that tea is healthy and one should drink it. Nevertheless, most definitely this conclusion is grounded in Daoist arguments made centuries ago but now forgotten. The statement feels “clearly true” within the cultural group of certain generations of Chinese. Even if one does not like tea the assertion would be difficult or impossible to challenge successfully to this group. It originated out of a *worldview, then just became an enduring cultural feature, it became “common sense.” Most Americans can be convinced that tea is healthy but perhaps only those who have embraced a certain *worldview associated with health food culture will think this claim so naturally true that it is not open for challenge, that it is just “obvious.”

We have another reason to pay close attention to *worldviews. *Worldviews are so widely held within a group that, besides being almost unassailable, they are also often almost invisible. Everyone is sipping the same drink. Again, we encounter here the concept of *”horizon of expectation” where some notions are entirely unnoticed, or entirely unconvincing to a certain group. *Worldviews do not change easily. If you say that true love is eternal and I say reject your claim by saying that no love, even “true” love, lasts forever, then we might be making our respective arguments based on two different *worldviews. Greeks and others will assert that the enduring nature of an object or idea is a mark of its truthfulness and goodness while Buddhists will say that there is no such thing as enduring nature. Claims such as “happily ever after” which assert that the outcome of a narrative is good and enduring sound naïve to a Buddhist.

The Korean film Chunhyang (Chunhyangdyun, 2000) has a happy ending but then chanter-narrator sings at the very end, “… but who knows what will happen after this story?” The Korean film 3-Iron (Bin-jip, 2004) also seems to conclude with the lovers united but then these white-lettered words appear on the black screen after the final scene: “It’s hard to tell whether the world we live in is a reality or a dream” and by so doing the sense of closure is completely subverted. I would like to suggest that these two Korean films make their rhetorical nods to Buddhist truth for the same practical reason: both director’s wish their films to be taken as making serious statements about the world and both feel the credibility of the content of the film is enhanced by touching bases with widely accepted Buddhist notions of impermanence, thus side-stepping a possible (and possibly devastating at the box office) criticism that their film content is naively over-optimistic.

*Worldviews (how the Universe works, how people can be expected to behave based on their essential nature, and how societies made up of such people function) then, tend to be widely held, relatively unassailable, highly influential, and often unnoticeable.

13.2.3. Discovering relevant worldviews

In our work of cross-cultural interpretation, *worldviews are exceptionally important but, unfortunately, they usually cannot be deduced from the text. Because the author and the audience share the *worldview, it needs no gestures to it, no explanations. “All men are created equal …” makes a regular appearance in American discourse, I would suggest, not because it is our *worldview but rather because it is not — it is an aspiration, not a description of how things actually are. Contrary to this, it would be rare these days to find any statement that attempts to convince the reader that children have rights. But, in fact, this is a relatively new *social worldview of what childhood actually is. If I had to reconstruct a Japanese 11th-century aristocratic *worldview for children it would probably be “they are things that—if they do not die while still young—confirm family alliances, are to be taken care of by others, kept out of sight, educated to be marriageable, and then promised into marriage at an early date (say 12 – 14 years old) to strengthen certain political positions of the family.” These attitudes are nearly invisible but, across hundreds and hundreds of pages of premodern texts with the occasional appearance in the narrative of children, I think this is a reasonable description. (Actual children in empirical Heian Japan may well have a different status. I am talking about within narrative.)

Here is a practical matter: If *worldviews are difficult to find in a narrative because on the one hand they are beyond your own “horizon of expectation” and on the other bereft of narrative clues bringing attention to them but nevertheless the *course method requires that you find the *worldviews of cultures unfamiliar to you, what are you to do?

Indeed. What I think people usually do as a pragmatic practice is put little effort towards engaging this conundrum and just push forward with a range of small fixes of issues as problems arise, thus treating the symptoms more than the cause, patching things together with band aide like compromises. And if, still, things are not going smoothly (an interpretation, a job overseas, a marriage) we accept the ongoing discomfort, or if things fall apart, we accept the loss and label the cause as “cultural difference.” Certainly, when asked to generate an interpretation of a text well outside our comfort zone in terms of *worldviews in order to complete an assignment, I find that students solve this by deploying his or her own opinion rather than trying to meet the text on its terms, a much more difficult and time-consuming project whose usefulness pales in the face of a deadline. And, if it is not an assigned text within a class, all of us most of the time simply avoid such texts (or films) as irrelevant, puzzling, troublesome, or all of the above.

In this way, *worldviews invite our participatory resistance if they are different from our own and so they are one of the ways we can discover or feel differences in culture. Texts that operate founded on unfamiliar or unacceptable *worldviews seem irrelevant or irritating. We may find that we “don’t like” or “don’t understand” narratives that are grounded in *worldviews we reject.

And this is where we find perhaps our best help for the discovery of an unfamiliar *worldview. Difference and diversity are our best hope of catching our own *worldviews in action and thus becoming better able to articulate them, providing us then with interpretive choices.

13.3. Cultural contexts and ethical values

13.3.1. Defining “ethical value”

First, a quick definition:

Ethical values proscribe behavior—they tell members of a cultural group what they should do.

In other words, *worldviews state how things are, how things work (what are the expected cause-and-effect chains) while *values state what should be done and indicate cultural pressure to behave in certain ways. For example, it would be very odd to say “One should be impermanent.” *Worldviews state how things are, not what one should do.

13.3.2. Determining relevant ethical values

But identifying *values and using them for interpretations is, as you can guess, no simple matter.

To begin, I would like to establish a rule to help with clarity in our discussions. When we use the word “value”, I would like us to take care and phrase things as necessary to make sure we are not confusing the various meanings of “value” which include: an *ethical value (a *principle), something that is widely regarded as desirable (such as “independence” in sentences such as “Americans claim they value independence”), and a measurement (such as “the value of that house is now almost nothing”).

Then, we should be clear that there are *values and then there are *values. What I mean is that there are ethical ideals (principles) that a cultural group might uphold as an aspiration (such as “one should always be honest”) which are often considered but not, in the end, all that active in deciding behavior (although they might generate guilt or shame about behavior), and there are *values that really must be kept, such as *loyalty to one’s mafia boss if you are a member of that cultural group. So, when we identify a *value in a film, we also need to consider where it might be on the spectrum that has “that is a great idea but” at one end and “that is something I really must do” at the other. Values do proscribe behavior but that does not necessarily mean they lead to behavior. Some *values do, some do not. It depends on many things. We identify *values regardless of whether they are near the “must do” end, because we are trying to construct not just reasons behind the actions or reactions of a narrative figure—we are also interested in that individual’s thoughts and feelings, including the confusion that might be the result of the belief that X should be done but Y happens instead.

Furthermore, most interesting narratives deal with conflicts and some of these conflicts are the result of conflicting *values. In other words, it might not be enough to identify the dominant *value that leads to the thoughts, feelings, or actions of a narrative figure. It might be a better interpretation to know from among what *values a selection has been made because such alternative *values rarely disappear. They continue to be in the environment, putting pressure on or informing the narrative. For example, the central female protagonist of 3-Iron mentioned above feels duty bound to be a good wife but her husband abuses her. She has strong thoughts to escape this situation and some degree of a wish to seek revenge. These three conflicting *values—a wife should be a good Confucian wife no matter the situation, a modern woman should take action to improve her personal situation, and a person who has done something bad to you deserves to be the object of revenge—play out in complicated ways in this film.

13.4. Distinguishing between worldviews and ethical values

13.4.1. Exploring differences of worldviews and values via the interpretation of the 5 Centimeters instance

I would like to return to my interpretation of the *instance in 5 Centimeters Per Second, which was:

The boy is holding back the essential loneliness of life for a brief happy moment with the girl he loves. His heart is full to bursting with the painful contradiction of two facts: he can be with her now but soon will be separated from her. Yet, being young, these painful feelings are strong but still somehow vague. He is learning about life.

What part of this interpretation is derived from considerations of *worldviews, of *values, and what part results from other random considerations? The short answer is that it is almost entirely written with what I believe to be modern, common Japanese *worldviews in mind because, I believe, keeping these “not naturally me” *worldviews clearly present in my mind as I arrive at tentative conclusions is my best hope of staying culturally close to the text rather than projecting my personal *values and personal cultural predispositions on it. Of course there is still a considerable amount, perhaps too much, “me” in the conclusions—it is not that easy to escape one’s culture.

When I wrote the above interpretation, I felt I was sort of writing in a foreign language, but I also felt some intuitive sense of “accuracy.” That sense, I believe, comes from an internal “check, double-check, and then conclude” process. I ask myself:

- whether I have aligned the interpretation (and the exact working of it) with *worldviews that I think are legitimately there,

- whether I have deployed a credible blend of *values, and

- whether I have, in the end, “stayed real” by considering:

- the narrative as it is delivered in its totality (the narrative context, all the multimedia information, what I know of the director), and,

- my “common sense” (which needs to be used with great caution since it is overloaded with cultural assumptions).

If I am lucky my conclusions have been tested by sharing them with others (usually my students) and observing their reactions.[4]

Here is my interpretation, broken down into parts based on different sources for what I concluded. I did not write from these sources. I considered all types of things, wrote an interpretation that I was comfortable with, and have only now gone back to see if I can determine what is behind my conclusions. Starting with the *worldviews and writing something that upholds or reveals or restates them is likely to lead to stilted, unnatural sounding, unconvincing observations. Please keep that in mind.

Here, again, is the interpretation, followed by explanations as to the concepts behind some of the phrases:

The boy is holding back the essential loneliness of life for a brief happy moment with the girl he loves. His heart is full to bursting with the painful contradiction of two facts: he can be with her now but soon will be separated from her. Yet, being young, these painful feelings are strong but still somehow vague. He is learning about life.

*essential loneliness of life. This comes from Heian period literature’s extensive discourse on separation and waiting for lovers and post-World War II “I-novel” expressions of loneliness and isolation of the protagonist, and probably a general hyper-awareness of relationships and lack of them that I sense in Japanese narratives. Japanese social worldview.

*a brief happy moment. This comes from a particular *value, expertly articulated in Oe Kenzaburo’s novel about a woman who experienced all manner of horrible things in her life, Echo of Heaven (Jinsei no shinseki, 1989). He described her smile as always akkerakan, by which he means to be cheerful when confronted with dark and depressing things. We see the same smile in the Chinese film 2046 (2046, 2004) as defining Lulu’s approach to her bitter life, and (somewhat more ambiguously) in many other of the narrative figures of that film, particularly Chow and Bailing. I do not consider this sense of being positive as specific to Asia (think of British “stiff upper lip,” for example) but this particular *mix of awareness of the bitterness of things plus “continuing on” (gambaru) is, I would suggest, very common in Japan. Japanese worldview (life is bitter) plus Japanese ethical value (one should show outward positivity regardless of what you feel inside).

*painful contradiction. Freud, literature, my study of religions (confronting the pervasive human urge to find answers to things), and life in its many challenging twists and turns, all tell me that the human condition is almost always one of painful contradictions. Personal social worldview.

*soon will be separated from her. Japanese embraced very early in their cultural history Buddhist impermanence, change, and that change is perceived as painful by those of us who are enlightened. It has left a mark. It has been immortalized in the “beauty of the cherry blossoms which will soon fall” cultural meme but is broader and deeper than that would suggest. Japanese cosmic worldview.

* being young, these painful feelings are strong but still somehow vague. This is my nod to much about this film that takes up, in my opinion, the theme of the process of “what it is like to have a first love, and how things change after that” as well as the fact that nowhere in the scene (or elsewhere) does this boy articulate with clarity his feelings of this moment, nor does it look like he is experiencing them with much internal clarity. They are just, in my opinion, sort of washing over him. That’s how I read his expressions and comments during this scene. The literary critic inside me asserting itself.

My final comment just steps back and looks at the whole of what I just asserted, and reacts to it in a summary way.

13.4.2. Worldviews and values mixtures

What I would like to point our attention to now is the interpretation resulting in “a brief happy moment” because it is a good example of one typical challenge when using the *course method, namely, a *mixture of *worldviews and *values. While it is not that difficult to offer distinctive definitions for “*worldviews” (how things are) and “values” (what one should do), *values are probably in almost all cases, in their essence, the result of *worldviews: because of how things are, one should …. . In asking yourself the source of your interpretation you might find that you are not sure whether you are dealing with a *worldview, a *value, or both and probably it is both.

13.5. Cultural contexts and common practices

Our thoughts, actions, and feelings are heavily influenced by the “*common practices” of the group in which we feel we have cultural membership. It is the law, when driving, to come to a full stop at every stop sign. However, “we” (the cultural group that could be defined as “American drivers under the age of 80”) can say that the “common practice” is the “rolling stop.”

Arguments over what is and is not a *common practice are probably arguments about either the defining characteristics of the group or one’s membership in it. It may be a Japanese *value to always gargle when coming in from the outside to one’s home but is it “common practice”? The outcome of the debate on that is likely to determine one’s action. “I don’t gargle” can mean “our group doesn’t do that anymore” or “I’m not that sort of *traditional Japanese man.” Christianity might teach “turning the other cheek” but many people who also call themselves Christian might not look too harshly on little acts of revenge. And so on.

*Common practice can be the result of basic “common sense” (“It is common practice to avoid a dark alley”) or more culturally-bound (“It is common practice, among some in Japan, to send a thank you card when you receive a birthday card.”)

We take this position for the method of the course: We recognize that common practices might be the single most important set of contexts to consider when building a credible ToM and we will duly note their influence. We will nevertheless look beyond them to see what *worldviews and *values might have a role to play, even if, by comparison, that role is much less. We do this because our project is to explore the impact of premodern cultural positions on our modern thoughts, feelings, and actions through constructing *ToM about love. Again, we are not simply trying to produce a meaningful interpretation of a text or film. We take that as an opportunity to think culturally.

That being said, we will definitely take notice when common practices are ignored. They are likely a signal of something. If you do not know me well (for example, let’s say we have offices on the same floor of a building but have never had a true conversation) and say to me, “Good morning” and I answer, “It is not good!” I have stepped outside a *common practice. It would be natural and correct for you to wonder why I did so. This might be a clue that leads to other discoveries.

13.6. A note on situational factors

Just for the sake of preserving perspective, when we begin to “make sense” of a narrative, that is, offer explanations for the thoughts, actions, or feelings of a narrative figure or speculate on the *worldviews and *values of the author/director, *situational factors that are often not cultural are actually more dominant. The particular situation of the story, the genre of the work, all sorts of things, actually have the greatest influence and are the best predictors of thoughts, actions and feelings. We might need to draw on these to arrive at a firm and credible understanding of what we are discussing but we cannot stop with just these contexts for interpretation since our interest in, again, in whatever *cultural contexts might be present, however unimportant. We will discuss the relationship of *situational factors to our *interpretive projects later in the book.

- FN: Dolls (Doruzu, 2002), which we usually view in this class, builds an entire painful sub-story around this concept of love expressed as box lunch but ultimately the two are separated. ↵

- Jeffrey Richey, "Mencius (c. 372—289 B.C.E.)," Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, accessed January 9, 2018, http://www.iep.utm.edu/mencius/. ↵

- Xunzi, Xunzi: The Complete Text, trans. Eric L. Hutton, (Princeton University Press, 2014), 248. Kindle Edition. ↵

- Interestingly, it is often the case that "natives" of the target culture (in this case Japan) who are class members will not weigh in as to the accuracy. Most of my overseas students consider it rude to "correct" the interpretations of non-natives to the culture or, sometimes, have a surprisingly high level of self-doubt about their own ability to understand their culture. This, I think, derives in part from their knowledge being instinctive and intuitive rather than discursive. They just "know" whether an interpretation is or is not on target but cannot necessarily say why they know that. ↵