White noise ◆ common practices ◆ love narrative circle ◆ the focus of interpretive projects ◆ steps and elements of the interpretive project: film, instance, ToM, narrowly defined topic, cultural context, context-to-Tom distance, outcome ◆ topical intensity spectrum ◆ status spectrum ◆ context robustness and ToM receptivity

— Terms —

- Introduced:

- derivative

- fragment

- framing question

- love narrative circle (love circle)

- narrowly defined topic

- receptivity

- robustness

- situational factors

- status and its spectrum

- topical intensity and its spectrum

- white noise

- Mentioned and should now be familiar (review if necessary):

- array

- authoritative thought system

- bounded dialogue

- CDE report

- common practices

- Connectionism

- Connectivism

- context-to-ToM distance

- course method

- cultural attractors

- cultural context

- discovery

- East Asia

- horizon of expectation

- instance

- interpretive projects

- narrative figures

- ToM

- traditional

- values

- worldviews

This chapter makes some final statements that sit at the border between theory and practice, with the various complications of practice being the primary source for its content. As I sometimes tell the class before we begin actual interpretive projects, the actual process is much messier that the theory would suggest. All sorts of conundrums and confusions arise. Indeed, the entire theory itself is meant to limit these to a reasonable extent but also leave space for discovery which, in my experience, has often arisen from the less constructed, messier, unbounded aspects of the work.Given this “borderland” positioning of the chapter, it is one of the chapters most likely to be in constant evolution, as practices in the classroom suggest new wording, changed directions, warnings, explanations, and so on. Much that is in the chapter could be in the chapters on method and much that is in those chapters could be here. What follows is my current decision as to where is the best place the locate material but it is a close decision. It is probably best to think of most of the below content as some hybrid of theory + practice.

17.1. Dealing with situational factors: “White noise,” common practices, and the “love narrative circle”

I have explained elsewhere that what we do is construct plausible content of *ToM, that is, the model of an individual in terms of the best guess as to her or his thoughts and feelings as well as the best guess as to the reasons for her or his actions or reactions. Since our *ToM are those of *narrative figures these “best guesses” are offered as plausive constructions of their thoughts, feelings and actions since, empirically speaking, they do not exist and thus cannot be tested except to the extent that when offered to others those others find them convincing.

There are a few things about such *interpretive projects worth restating here in the final chapter on theories and assumptions of the *course method and before we move into the templates and other mechanics of the projects themselves.

17.1.1. Avoiding “white noise” and focusing on worldviews and values

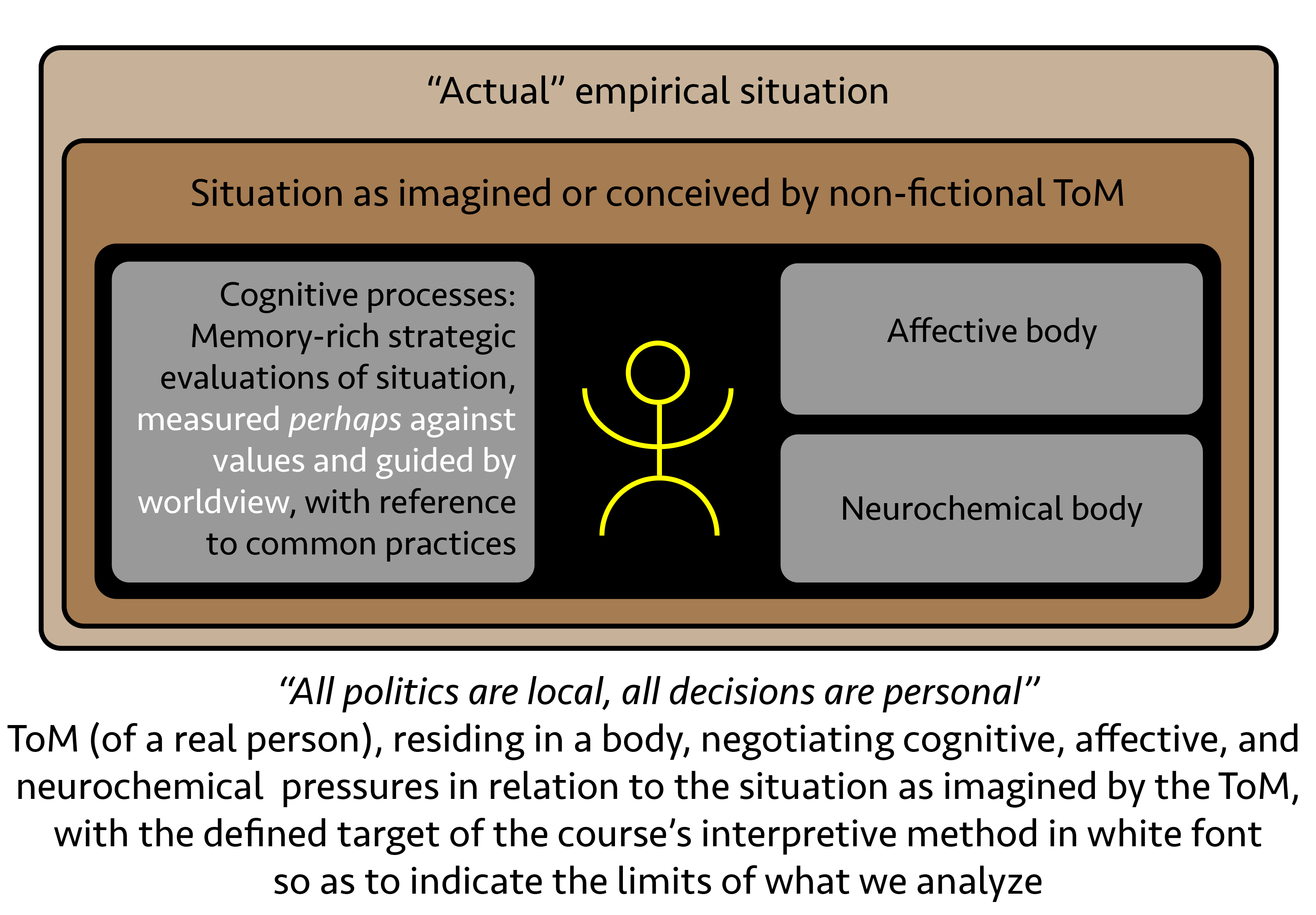

First, I acknowledge that if the question were not “What *worldviews and *values might be worthy our attentions as we work towards a plausible *ToM that is embedded in a specific culture, not our culture necessarily?” but rather “What is someone thinking, feeling and why do they do what they do?” we are in an entirely different analytic environment. (Our interest in talking about *ToM rather than *narrative figures or people in their totality is not just jargon—it is designed to draw us away from the more fleshed out presence of the full figure.) If our concerns were to explore the mind and heart of an individual, and ponder the causes for his or her actions or reactions, the most useful elements to consider would include strategic concerns (*situational factors and strategic considerations arising from them), natural visceral reactions (real people have bodies with affective and neurochemical aspects), habits, *common practices (“What does everyone do in this sort of circumstance?), and patterned behavior (behavior patterns learned from others and just repeated without any extensive thinking about entering into that pattern).[1] Nearly all of these, in many cases, will have a more important role in determining the thoughts, feelings and actions of someone rather than the values they hold or aspire to. It is less clear to me whether it is as easy to set aside *worldviews or have them trumped by these other elements because *worldviews are the very basis of strategic thinking (“Since the world works like this, if I do that …”) and also are deeply involved in generating the *horizon of expectations that presents some options and makes others never even known to have been options. Deciding this question is not necessary for our purposes because we are in any event already pre-positioned to ask questions about *worldview and *values and set to the side these other considerations.

These important *situational and other considerations are prominent and distracting and, based on a casual conversation in the hallway with a student in 2018, I have decided to give them, collectively, “*white noise.” (However, while that conversation was about possibilities *white noise afford to draw out textual[2] features, I am using it metaphorically as an overabundance of randomly present features that makes it more difficult to “hear” specific notes or melodies clearly.) Functionally speaking—that is, in terms of achieving good interpretation—what I will call *white noise is any or all prominent features of an *instance that are important for understanding the non-culturally specific basics of the *ToM’s situation but in their prominence and familiarity distract us from finding more nuanced cultural insight. They can impede interpretation by their very presence.

So, we recognize that in the real world, thoughts, feelings and actions / reactions arise from complex interactions of many levels of our being:

This graphic illustrates an individual, not a *narrative figure, amidst a plurality of forces: hopes, wishes, worries, fears, health, cognitive calculations based on the *ToM’s best understanding of the situation (which might, by the way, not be very good), referencing memory and the behavior of others. From this complicated situation we make two decisions from the purposes of manageable analysis: we limit ourselves to the less complicated constructions of *narrative figures and we further limit our scope to simply asking what role, if any, not just *values but the subset we can call *traditional values might have in such a complicated environment. We turn away from an essential interest in the individual to an interest in how *traditional *values have or have not survived, have or have not transformed themselves. We are not trying to explain the individual, we are interested in the *values.

I would like to say that there is wisdom in limiting the scope of our project so as to make is manageable enough for meaningful discussion. Discussion is not just a beneficial activity for this course; my assumptions about *cultural attractors and *horizons of expectation make discussion the single best antidote for these errors in judgment, in cross-cultural interpretation. I would also like to offer my considered opinion that while considering what role *worldviews and *values have in determining thoughts, feelings and actions might not be the key factor in making final determinations about these things, the process itself is the same. The ability to set aside one’s preconceived views and consider the environment of the *ToM from the perspective of the *ToM, especially when it might require learning something new to do so, is exactly the right process for making sense of one’s world and puts one on a fast learning curve toward sorting out the puzzles of a new cultural environment in determining why others behave the way they do and how oneself should behave as well. This understanding is undeniably powerful. (I would hope that individual would use this understanding for the good but it is, in fact, a morally neutral understanding in my opinion and can be used just as easily for selfish or unkind success.)

However, among features that might act as *white noise, there are two that we do, indeed need to pay close attention to. The first, “*common practices” deserves our attention because these may well be culturally specific and so are likely to help us understand the cultural terrain of the *instance. The second is narrative progress location. We need to know “where in the story, at what point in the storyline” our *instance is happening. This is the chronology generated by the narrative, the “time” of and in the story. We also probably need to consider “where in the text” the *instance is: First paragraph? Last sentence? Beginning of the most critical scene? And so on. Where an *instance is located in a narrative matters tremendously in our understanding of it. In this second category, we will consider in more specific terms just one type of location in particular, that of where an *instance is on what I call the “*love narrative development circle” or just “*love story circle” or “*love circle” to keep things simple.

17.1.2. Common practices

If this class was not squarely pointed towards asking questions about the *status of *traditional *worldviews and *values in contemporary cinema, *common practices would be a good way of exploring culture. I settled on this term because of the gap we all know and understand between the ideals of a culture (its ethical principles) and what really happens in the world. For example, a core Christian principle is “love your neighbor as you would love yourself” and the *value that this represents is to some (including me) beautiful. But we all know that this is not the actual *common practice. The *common practice is closer to a *value that could be phrased “try to be a bit nicer to your neighbor than your natural impulses would lead you to act.” It is fair to call this a *value, too. It is just not an idealistic one; it is a practical one. Originally, I split ethics into three types: ethical principles (ideals), *ethical values (widely upheld and maybe not usually in reach but in principle practical reformulations that are achievable), and *common practices (what people actually do and do so commonly and widely that one would not be very criticized if one follows the practice, even if it is not very nice as an action). This discontinuity between ideal and practice is very important: rules need gaps, gears should not fit very tightly together, the imperfections, secrets, and “convenient” decisions around the edges of things are part of how society remains functional. Because of this original three-part scheme, you might still encounter the word “principles” here and there in this text. It is a good schema. But I try to slim the theory when I can.

We decide whether or not to treat *common practices as *white noise based on whether we think including it or excluding it is the best for drawing out the cultural features of the *instance. I would also ask that you keep in mind that it is all too easy to project one’s own *common practices into a narrative and thereby miss its cultural differences from you.

17.1.3. The “love narrative circle”

Understanding an *instance almost always requires considering where it is in the development of the story. We use a template called “*love narrative circle” (“*love circle”) so that we have shared language when discussing our various interpretations of an *instance. It is not unusual that different groups will plot an *instance differently on this circle. That is a good thing to know. It clarifies where the disagreements between the groups are.

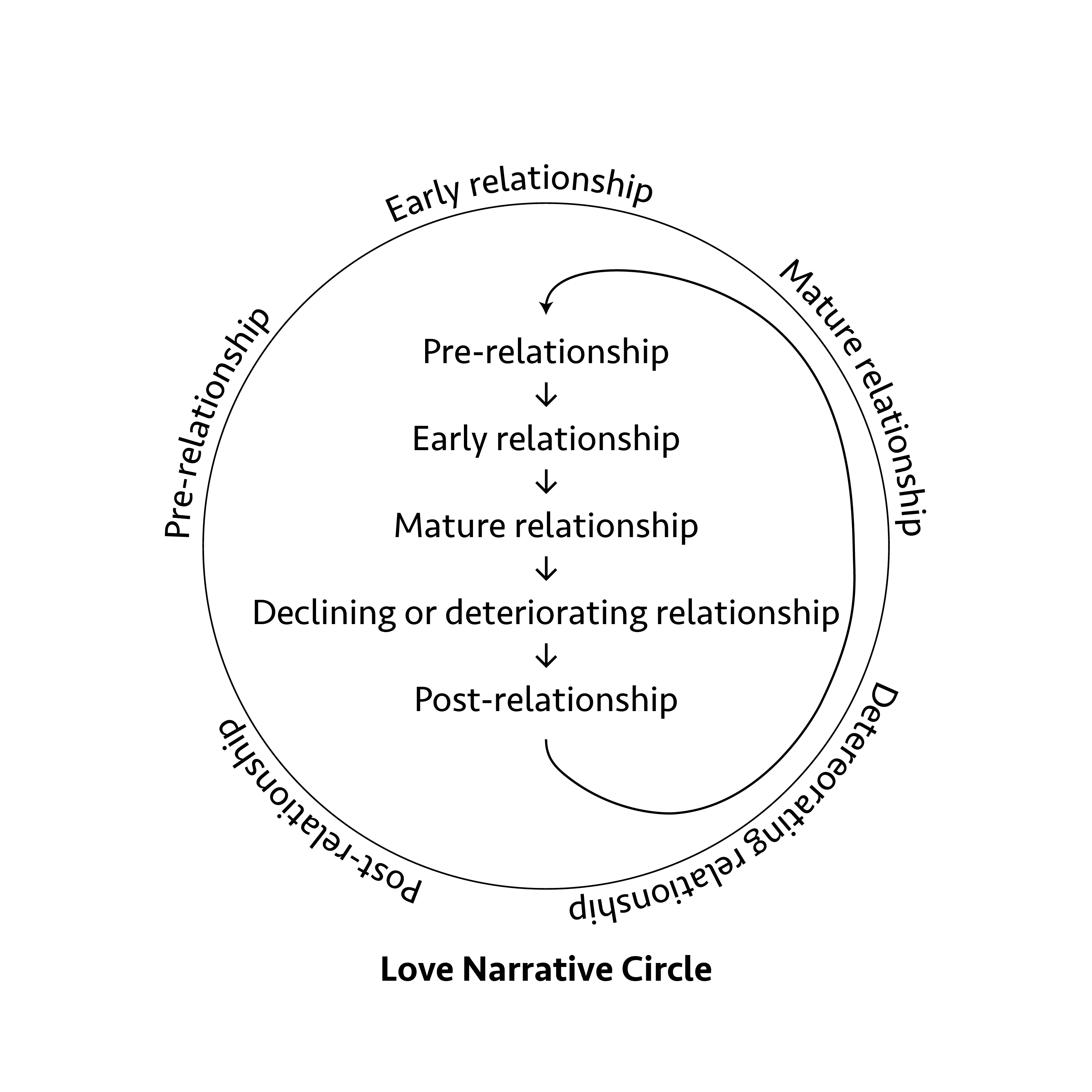

The typical Western view of love (and many other things having to do with narratives) does not often use a circle. It is more likely to be linear: lovers are challenged and either fail to overcome those challenges and are forever apart or do overcome those challenges and live “happily every after.” I will argue in the discussion of Daoism that cycles are the foundational geometry of *East Asia and since we are talking about *East Asian love stories, I have selected the circle as the shape on which to plot various stages of a love relationship.

The *love circle is a narrative development map where we plot an *instance on a narrative event chain that is the love narrative. Its five main phases are: pre-relationship, early relationship, mature relationship, declining or deteriorating relationship, and post-relationship. This is a basic conceptual structure / formula: birth–life–death of a relationship + a “before” and an “after” stage. I believe this is the minimal structure one can offer for any narrative that has temporary existence. For example, this segmentation is followed in the five books of love of the Japanese Poems Old and New (Kokin waka shu, 11th-century Japan).

We plot an *instance on the *love circle as best we can to better understand its situation and for purposes of more meaningful comparisons with other love narratives.

Please note these features of the *love circle:

- Clearly, the five main phases themselves can have subdivisions. For example, if the relationship “seems like it is beginning to fall apart” that would be an early moment within the declining phase.

- The content of these phases is not necessarily obvious. A “mature” relationship might be one that feels stable and secure. Or it might be a time of conflict after the initial phrase of falling in love fades and the couple realizes they are in a long-term relationship.

- It is likely that the *ToM does not have one fixed mental location on the circle. For example, “I think I have stopped loving this person … but maybe not.” Or, “Yesterday I was sure I was in love, but today I feel nothing or seem to be going back and forth. I’m not sure.”

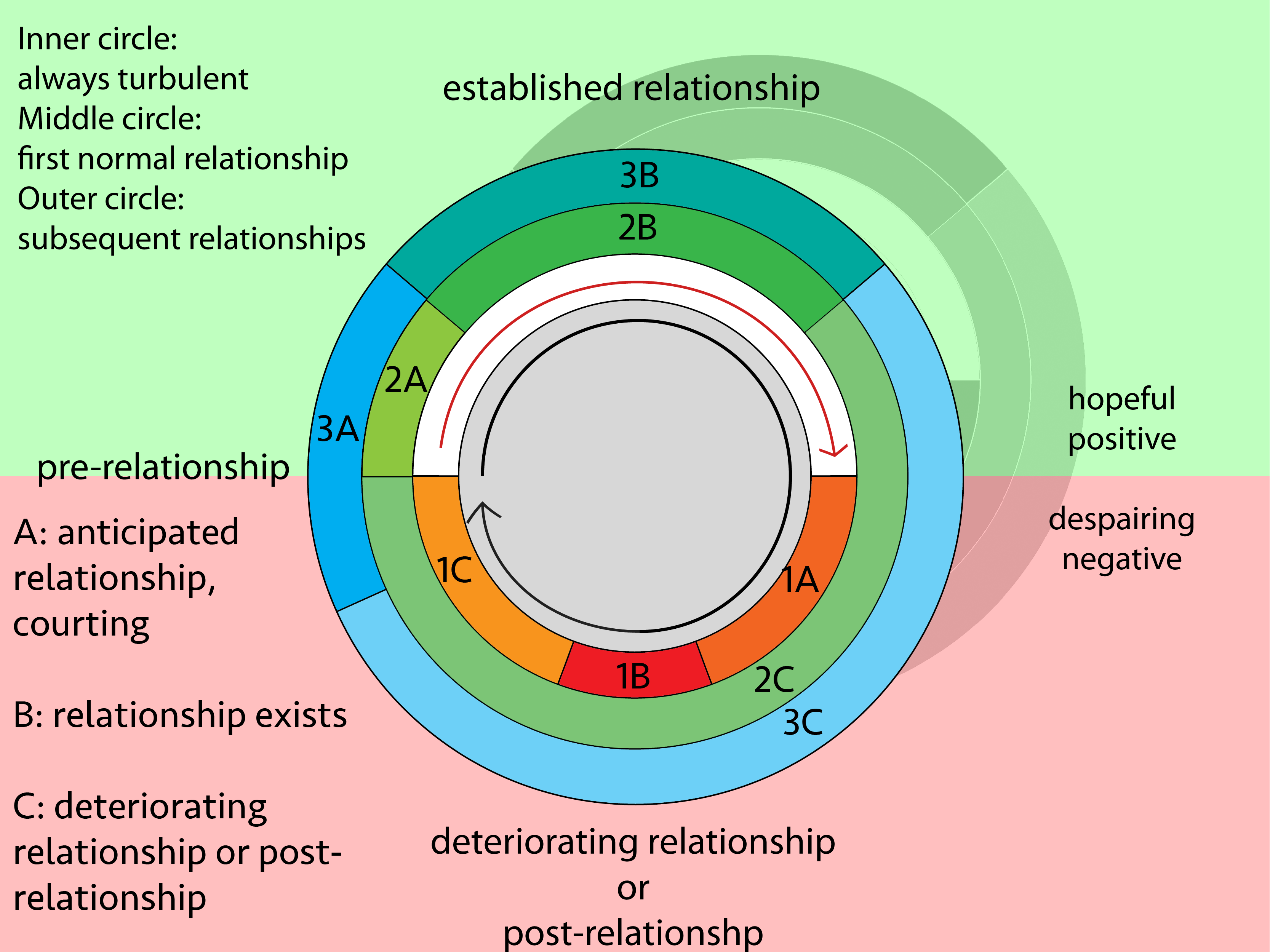

- It matters a great deal whether this is the “first” circle that the ToM experiences or instead a repetition of the love cycle (a second or third or still more cycle of love).

- Finally, there is no reason to assume that the two individuals in a relationship perceive the relationship in the same way and so would say the same thing, if asked to plot it on a circle. Consider this example:

- In House of Flying Daggers, Xiao Mei’s love towards Jin remains in a pre-relationship phase longer than that of Jin, who has accepted her I his heart. However, in a more general way, this couple can be seen as being in the aspirational and hopeful stages of early love more than the Xiao Mei-Leo pair, which is fully mature and is probably in the early stages of decline. The tension in the film surrounding her inability to decide between the two men is not simply because of the differences of values of the two men or her different feelings toward them. It is, fundamentally, a tension of two love relationships at different stages.

Here is the love circle in its basics:

However, I would like for us to keep in mind the implications of love cycles and repeating love cycles, as well as some variations:

The above is a diagram made several years ago, when I had a three-part rather than five-part phase system, but it is still relevant in a number of ways:

- It represents the memories of previous circles with the shadowed circles behind the main image.

It suggests that the basic environment for a love narrative is either optimistic or pessimistic, which is often but not always the case. The graphic offers this as something to think about, not insist on. - With the innermost circle it suggests that it is possible to be pessimistic about a relationship right from the beginning.

- It suggests one way that a second cycle might be different from a first. This is of course just one of many, many ways a first love and a second love can be different in terms of narrative progress.

17.2. What role do authoritative thought systems have in shaping content of contemporary cultural groups?

This course was originally designed with the first half of the semester spent reading premodern texts. That was primarily a way to inculcate against overly modern, overly ethnocentric interpretations of love stories. I believed that if we had a stronger and better-formulated understanding of Confucianism and such in their classic, early forms then those alien-feeling and crisply defined features—should they exist as traces in modern situations—would be easier to notice and tease out of the text of film, helping us read with better cross-cultural accuracy.

While we no longer spend extended periods reading premodern texts, this basic position is unchanged—the emphasis has remained on *traditional *worldviews and *values. I continue to believe that knowledge of them helps us notice and understand cultural differences worth noticing, despite our postmodern relationship to traditions, despite globalized culture, despite the spread of individualism around the world, despite many things. Among this crowd of modern ways of thinking and among our fractured cultural terrains, these *worldviews and *values, I suggest, have indeed retained a place and it is perhaps these, rather than a wide range of other social practices (common practices), that generate significant misunderstandings and misreadings.

And so we circle back to the basic question: What role, if any, do *authoritative thought systems have in shaping culture and cultural differences ( …. in *East Asian films)?

This is a way of asking how relevant a *cultural context is. We try to locate *cultural contexts and suggest their interpretive relevance via *interpretive projects.

We try to determine a disciplined measure of this through a triple-faceted process where each area of consideration interacts with the others until we find a balance among them that seems, above all, to be the best in terms of credibility, but also, hopefully, of interest to others. In this case, “of interest” means either observations of culture that seem promising for further analysis, or things that had gone un-noticed and once identified, erase a “blindness” of some sort. These three facets are: refining what of a *cultural context is relevant, deciding “distance” between the *context and the *ToM, and deciding the *status of the *worldview or *value.

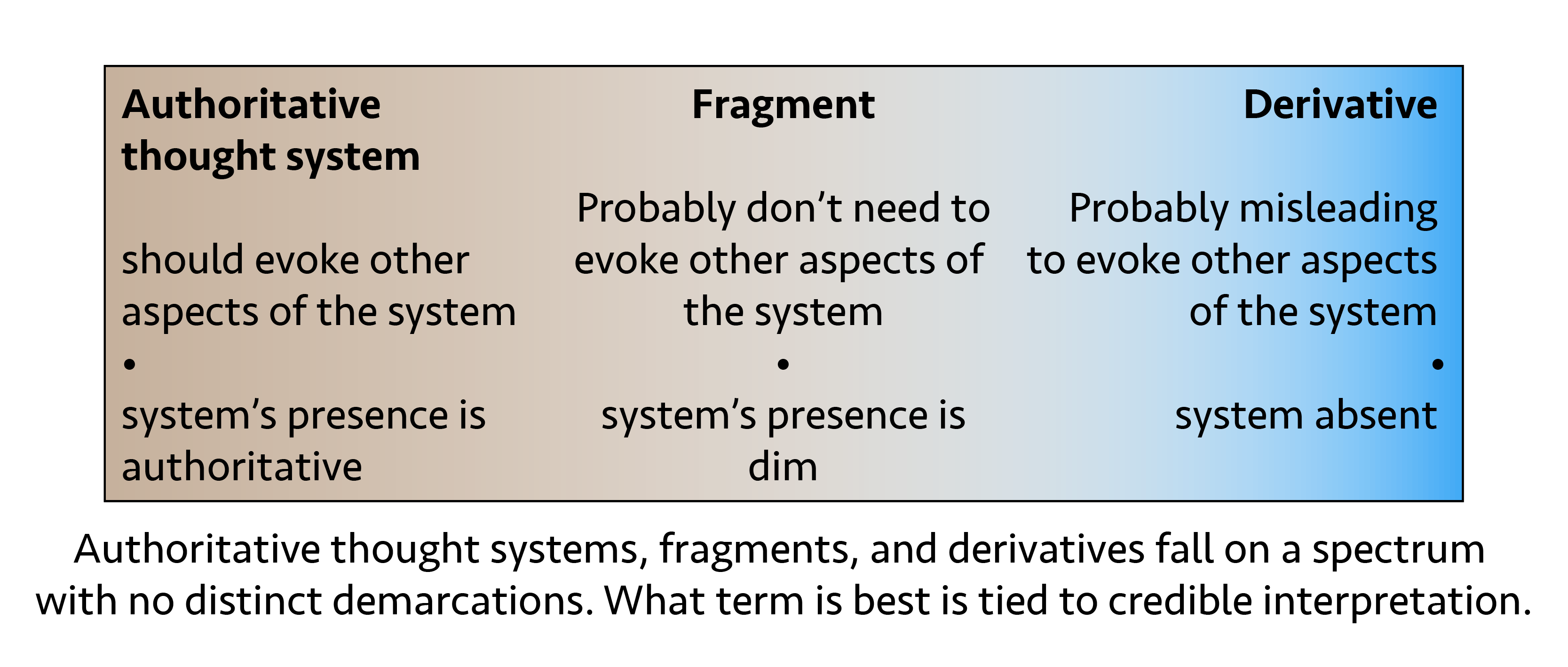

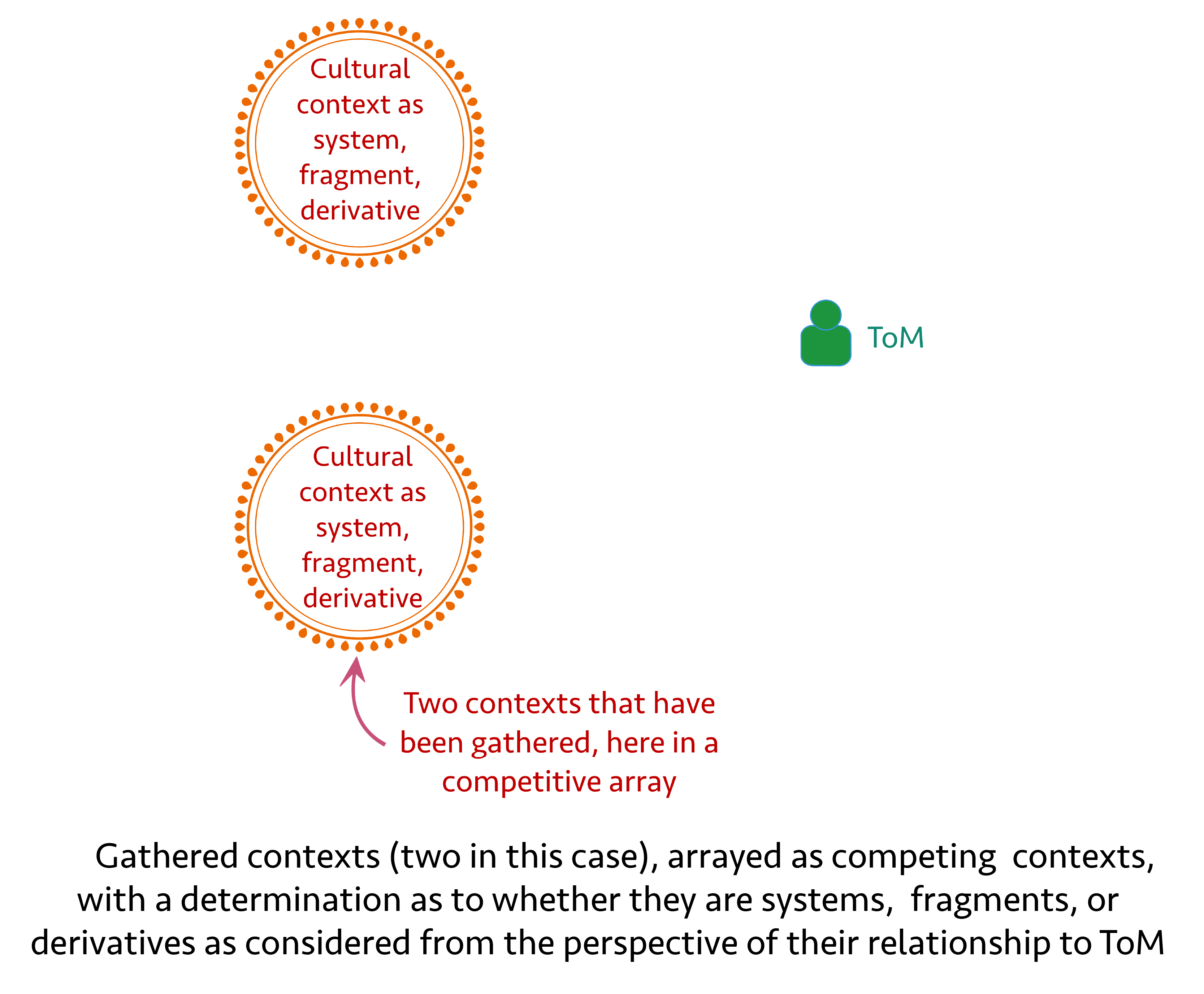

- Deciding specifically (refining) what of a *cultural context needs consideration. The interpretation is grounded on the best possible estimate of what needs to be considered, that is, whether we should keep in mind the full *authoritative thought system, or recognize what we need to work with is really only a *fragment of it, or, finally, deciding that the object is only a distant *derivative of an original system.

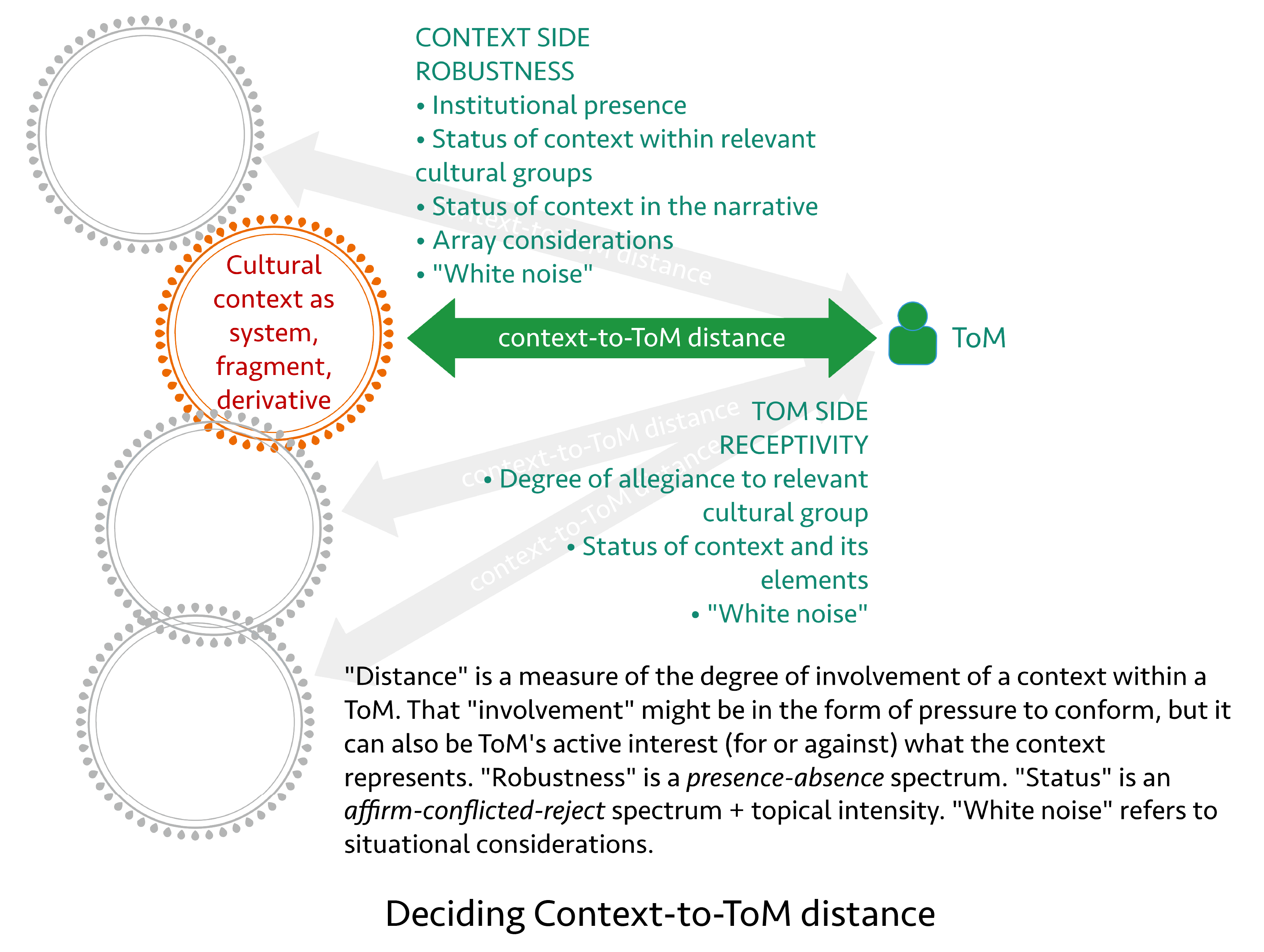

- Deciding the “distance” between the *context and the *ToM. We must take up at the same time considerations of “*distance” between a *cultural context and a *ToM which is a way of measuring the ability of the *context to press the *ToM into certain thoughts, feelings or actions/reactions or, alternatively, the level of willing interest of the *ToM in engaging the *context. “*Distance,” we will see, can be the result of many different factors but as a simple description it is the dynamic of a *context’s *robustness and a ToM’s *receptivity.

- *Status of a *worldview or *value or perhaps a *context in a broader formulation and its topical intensity.

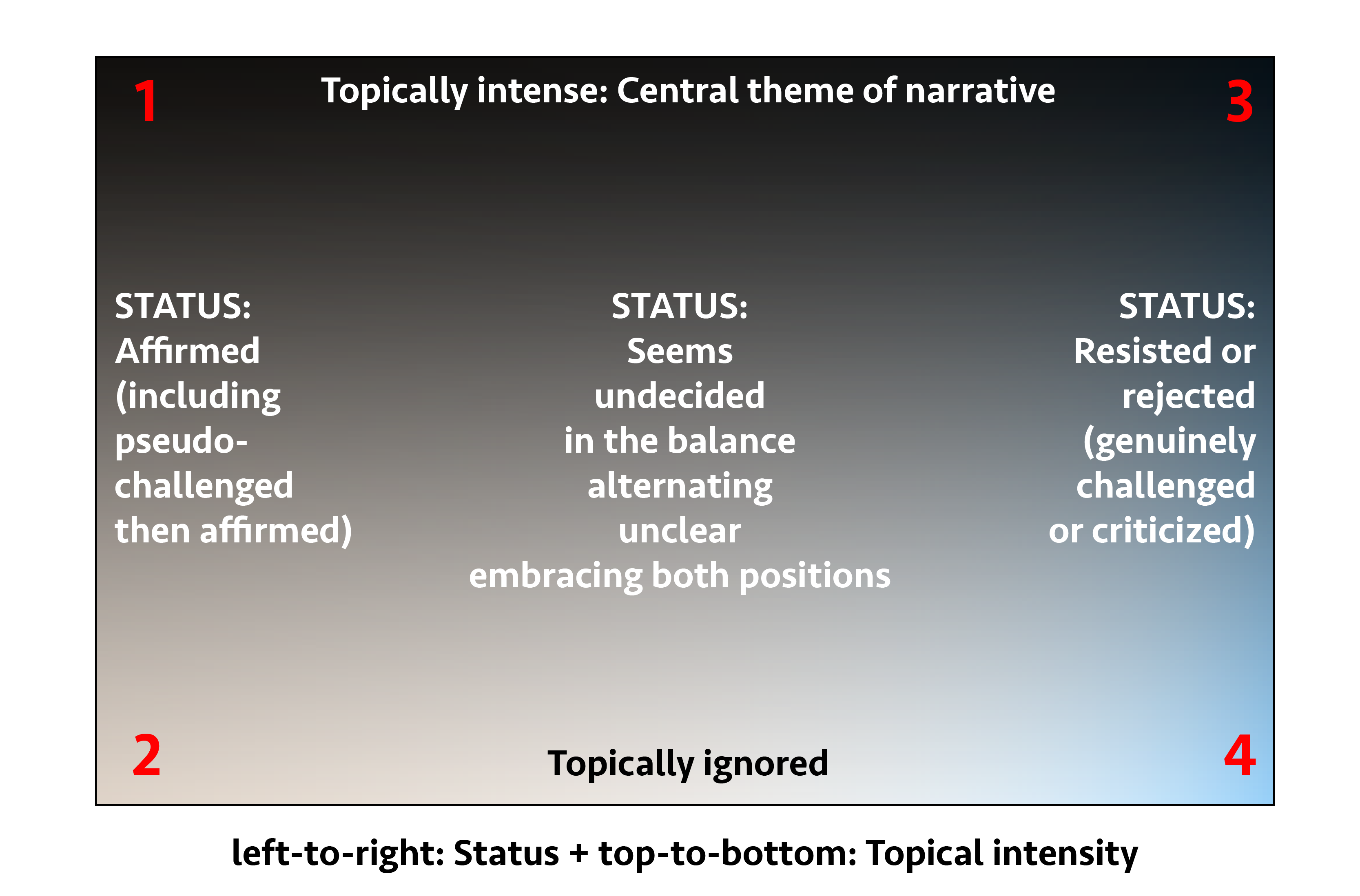

- We need, of course, to consider whether the “object” under consideration is viewed by the *ToM to be affirmed, or resisted, or perhaps there is a more conflicted or ambiguous *status. (In other words, does the *narrative figure residing inside the story appear to affirm or reject a certain *worldview or *value? Has the director constructed a world where it seems she or he affirm or reject the *worldview or *value? And so on.) The “object” here most often means a *value, since *worldviews tend to be unconsciously upheld and not often the direct topic of a narrative. (Nihilist works or hyper-religious works, however, challenge widely held *worldviews.) We call whether a value is accepted or rejected or something else “*status.” We plot *status on a spectrum across the range “affirmed-conflicted-rejected.” We need to keep in mind, however, that there are many ways of affirming something and, similarly, many ways of rejecting something. For example, in terms of affirmation, there is overt affirmation, complicity, passive acceptance, and many others. In terms of rejection, there is active and full denial, or changing the object to more acceptable forms, or ignoring the object at times when it should be the topic, pretending to misunderstand the topic, and so on. Further, the “conflicted” designation is meant to be vague and include not just “undecided” or “switching back and forth” or “unclear” but also when a value has been modified in a way that seems to suggest “the value itself is good but for it to be viable in our modern world it needs to be adjusted somewhat.” While one could see this as a type of affirmation, in a sense it erases the original when it modifies it so, in a pure sense, it is a rejection. Because of this difficulty, I feel it is better to leave it at the center. I think the spectrum schema is useful so I have decided to collapse it into the mid-point and include it with other “conflicted” positions.

- Onto this complex spectrum—which should be considered very carefully when building an interpretation because it is in this area that a great deal of narrative slipperiness occurs—we place as well a spectrum of “*topical intensity.” That is, to what degree does the narrative engage the *value or other cultural object? Finally, it should be further noted that *status needs to be calculated for multiple levels of the text because they influence one another. The basic levels are the *status of the object as it is from the perspective of the *ToM, its narrative world, and that of the author / director. How the *ToM thinks of a *worldview or *value, how broadly society embraces that *value, what seems to be the *status of that *value in the full environment created by the narrative (the narrated world), and how we imagine the author or director really feels, as this can easily influence content in both obvious and non-obvious ways.

The above three are developed contemporaneously, as we try different combinations until we are satisfied with the accuracy of the description and conclusions. Such interpretations, observations, and conclusions will of course be a matter of judgment and they may well change later when reconsidered, or upon hearing the thoughts of others, or when learning new and relevant information. Most of the conclusions in this course are tentative in this way although when many groups conclude along similar lines (within the class or across multiple iterations of the course), such conclusions might become a more solid conclusion. Nevertheless, the danger of “group-think” and “group blindness” needs always to be kept in mind.

Essentially the analytic destination of this course is to make credible suggestions as to what cultural features are worthy of note or what cultural features are interestingly absent, whether such features are being accepted or rejected, ignored or something in between, and with what degree of energy all of this is happening within the narrative.

We will now consider the elements and steps of an interpretive project, one at a time.

17.3. Outline of an interpretive project

Interpretive projects are the core activity of the class. It has multiple steps, some done by individuals, others by groups, and results in reports that are usually shared. It requires awareness of the rules, guidelines and specific terminology of the course, as outlined in the follow book part. The basic pattern is first to create a binding contract as to what will be analyzed (something like a prompt), then work through an analysis-outcome phase (hyphenated because of its hermeneutic nature: each of these develops together with the other), and finally sharing of the analysis-outcome. If the interpretive project is the work of a group instead of an individual, there is a second outcome phases where the analysis-outcome results of individual interpretive projects are debated and consolidated.

More specifically, an *interpretive project begins with the selection of film or text, a determination as to the *ToM, and an *instance within the narrative, then sharpening the focus of the work by defining a *narrowly defined topic. This creates an interpretive contract that, once fixed, cannot be independently altered or deviated from. The contract is a set of boundaries (film, *ToM, *instance) and defined focus (*narrowly defined topic). The *narrowly defined topic is broad enough to allow for exploration but narrow enough that if interpreters work independently they can later compare meaningfully their results since they are essentially working to answer the same interpretive question or questions. The *narrowly defined topic obviously must be devoid of prejudicial language, hypotheses, or conclusions in order to suppress *cultural attractors and other preconceived notions, on the one hand, and, on the other, create space that might allow for “ah-ha” moments that succeed in extending past one’s typical *horizon of expectation.

Once the contract is decided, interpreters gather *cultural contexts, *array them, and make succinct statements that represent their interpretive conclusions. They share these with their work group members. Group members’ conclusions are debated within the group and a *CG-C-D-E-R report is composed. The report is usually shared with the class.

The above is an overview of the basic workflow of the course *interpretive project. This work and the theoretical positions supporting it, are what I call the *course method.

In an earlier chapter, via an interpretation of an *instance in the Japanese film 5 Centimeters per Second, I laid out course definitions for *worldviews, *ethical values, and *common practices. In another chapter, I made suggestions on how to gather *cultural contexts and manage the complexity of such a harvest of possible contexts. Now, as we conclude this part of the book, and before we move into the specific rules, standards, and processes of the interpretive project itself, and thereby encounter the practical problems that *interpretive projects will bring, there remain a few more theoretical issues to address.

17.4. Elements of an interpretive project

17.4.1. The list of project elements

The elements of an interpretive project are:

Contract construction phase

- Framing question

- Film

- Instance

- ToM

- Narrowly defined topic (NDT)

Analysis-outcome phase

- ToM location on love circle

- Cultural context content

- Context-to-Tom distance

- Cultural context status

- Cultural context topical intensity

- Outcome (individual)

- Outcome (group)

Report phases (sharing)

- The individual or group engaged in interpretive projects reports to me, group members, or other groups, or the class as a whole through three report templates: project contract, individual project report, and group project report. (There is a fourth report sometimes requested which askes the group to report to me details of their meetings. This is for assessment purposes, not carrying out and sharing analysis.)

17.4.2. Framing questions

The “*framing question” is the start point of any *interpretive project.

*Interpretive projects work in narrow spaces in order to enhance the chance of discovery through *bounded dialogue. This narrowness, therefore, has an advantage but can lead to pointless debates if larger issues are not kept in mind. Interpretive projects are most powerful when they have a well-defined contract that captures into it a large and interesting issue and has found a way to explore that issue through a *narrowly defined topic. These larger issues are conceived by the individual and group and articulated and given direction through a *framing question. The authors of an interpretive project then “translate” this general idea, as posed by the question, into something that can be explored via the course method, with its terminology and specific process.

The *framing question, then, is:

- a question that is interesting, relevant, or otherwise useful in some way toward considering cultural differences and similarities among our *East Asian countries or exploring the fading or persistence presence (*status) of traditional worldviews and values—but is, itself, too large to have any realistic, credible conclusions only tentative ones,

- something that an interpretive project can offer insight towards,

- free of course jargon but instead is general, intuitive, casual, natural, or conversational in its language.

Interpreters then fashion defined areas of analysis to contribute focused thinking toward these sorts of broader questions.

Here is an example of a framing question:

“Is it useful or just a waste of time to consider Buddhism to help interpret the Korean film 3-Iron. Might it be better to consider the angst in the film to be more about Korean ‘han’?”

This would generate two projects that could be compared.

One might have a contract such as:

- Film: 3-Iron,

- Instance: Outcome of the romantic relationship in the film,

- ToM: Director,

- NDT: “What is the *status of a *Buddhist-like *worldview that change is experienced as the physic pain of unreliability and existential thinness?”

Such a project could then be paired with:

- Film: 3-Iron,

- Instance: Outcome of the romantic relationship in the film,

- ToM: Director,

- NDT: “What is the *status (with special attention paid to *topical intensity) of the *worldview that is the foundation for ‘han’?”

Both of these projects, by the way, engage three things mentioned elsewhere: 1) that an *instance is connected to its surroundings (therefore, to discuss outcome well the interpreter needs to think of the entire plot line); 2) a necessity for interpreters to engage in outside research in order to understand what ‘han’ is; and, 3) thought and debate around what exactly the outcome is—in other words, interpreters almost certainly will engage in the hermeneutics of using possible *worldviews to decide basic story meaning while at the same time using basic story meaning to decide what are relevant *worldviews.

17.4.3. Films: audience considerations and working with slippery content

The selection of the film is, for the most part, a practical matter. However, there are some theoretical points I wish to note.

First, thoughtfulness as to the author-text-reader (viewer) relationship is, in my opinion, paramount in any good interpretation and, when doing so, it can be a determining factor in film selection. There is much that could be said, but at this particular juncture I want to note that the commercial aspect of films is something we are unable to ignore in our interpretive projects. Because of a course premise (unproven, but nevertheless a premise by which we work) that one factor in box-office success or failure is whether the audience can accept the *worldviews and *values of the film, we need to ask—when deciding cultural contexts—the question of whether the *worldviews and *values primarily emanate from the personal vision of the director or his or her intention to reflect back to the audience what he or she perceives to be *worldviews and *values with which the audience is comfortable or enjoys. Of course, this is no simple matter since the director is, indeed, embedded in a culture regardless of how much he or she may wish to think otherwise, and, in addition, the director’s understanding of the audience is, itself subject to misinterpretation. Further, there is, in fact no single “audience” and films may well be targeting multiple audiences with different values. Much of this is, ultimately, undecidable and, in the end, a “best guess” or “one good guess” position must be taken simply in order to undertake at least one plausible line of analysis. Whether this is a final answer or not is not important since the goal of interpretive projects is not to generate answers but rather generate well-considered positions around which thinking can occur.

Second, because of their interesting in feeling “current” films have a convoluted relationship with almost anything that is *traditional and so not only may they have low *topical intensity (almost invisibly so) they often either contort the *traditional *value or have a contorted relationship to it (affirming it and denying it at the same time), or both. While this makes getting to the end of an interpretive project difficult, just that act of trying to carry out a project while being aware of these challenges teaches us something about the place of *traditional *values in current situations. So, in this particular case the struggle is what success looks like much of the time.

Students usually learn right from the first of their interpretive projects that the director’s view (or the “emergent” view of the film as a result of all of its collaborative elements) in slippery or sloppy or both with regard to *worldviews and *values. This is just a feature of the medium. Few directors enter into film-making because of an interest in philosophy or ethics (although some of the best do), but are instead more interested in the affective power of film, a topic we set outside the boundaries of our interpretation. Further, even if the director has a clearly defined set of *values, he or she is constrained by commercial pressures and the messy, collaborative nature of the art form. Besides box-office audiences, for example, there are those who fund the project and put their name on it. Still further, since the purpose of most films is, above all, to entertain not educate, *values, if they get in the way of an entertaining moment, show of predilection of temporarily and conveniently disappearing.

Finally, there is the very interesting nature of comic (wry, sardonic, cynical) expression: through humor one can be entirely ambiguous as to one’s position. In other words, the content of a comment can be real and “just a joke” at the same time, that is, in an undecidable replacement pattern where we can no longer say that, ultimately, it is one or the other. This type of comic or wry expression is exceptionally common in film—in comedies obviously (so beware of selecting comedies for interpretive projects) but in just about any film at some point.

17.4.4. Instances and their interconnectedness with what is beyond the instance

An *instance can be any aspect of a film or films that “freezes” the discussion around a particular “moment” or feature that allows for an exploration of the thoughts, feelings, actions / reactions of a *ToM.

In its simplest form it can be a moment in the narrative with a question such as “When X learns that her lover has been killed by her son, why does she choose to continue to protect her son?”

However, it can reach beyond a single film or a moment of the narrative time: “The director uses the color pink in all of his films at moment of violence. Is this tagging a specific *worldview outlook or *value?”

The hallmark of an *instance is not that it is a brief moment but rather has a single feature so as to avoid the fog of considering many things at the same time. That I have settled on the somewhat awkward term “*instance” is because I wish it to always suggest, in the very word itself, that it is dangerous to draw sweeping conclusions from interpretive projects since we look only at a limited “instance” of something, not a frequent feature or recurring event.

That being said, good *instances do suggest that the outcome positions arising out of them may well suggest something larger and, in fact, the hope is that they do. However, we simple remain on this side of caution and refrain from claiming that they indeed do.

“*Instances” are expansive in another way as well. In the vein of Derrida arguing for significance of words coming from the networks they belong to, the significance of narrative moments similarly derives from the larger narrative and the place of the moment within that narrative. This is the point of the *love circle: we cannot truly understand how the *ToM is thinking, feeling, or planning action without deciding where the *ToM sees itself as being on the *love circle.

In the same way, even in above simple example of the mother and her son cannot be asked without awareness of the full film. Her decision might be at one moment but we learn of it through larger narrative chains of her man actions towards her son and, indeed, there may never have been a moment of decision. Perhaps she is acting “naturally” and “instinctively.” If this is the case, our *instance has created an artificial moment in order to discuss the *values we think might be in play. As with much in this course, this sort of analytic movement points us toward a discussion of *values and away from an interpretation of the film. Considering the *status of *values trumps generating the best analysis for the film although clearly these two are deeply involved in one another.

17.4.5. ToM: two basic levels, “shadow ToMs” and other imagined objects, and the complicated relationship of ToM and its cultural contexts

Of course, what a *ToM is, why we discuss *ToM rather than *narrative figures or actual individuals, why we limit our investigation to *cognitive – (and some) *affective love within them, and the difference between real world *ToM and our made-for-interpretive-projects *ToM have all been taken up at various points in the book. *ToM is at the center of our work.

Here I would like to add one simple consideration and two not-so-simple considerations.

First, I would simply like to say that the selection of *ToM determines our analytic perspective: the world as seen from with a *ToM is always true but if it is a character in the story that world is quite specific and limited whereas if it is the director of the film, we are working at something of a “meta” level and considering all corners of the film. These are the two “levels” of *ToM but in truth the director’s level is never absent. That *ToM affects the way we should evaluate *ToM of the character level and that *ToM is, in many cases, the one we want, at some point, to end up thinking about. That being said, there is much good work to be done at the character level.

Second, when we watch a film we are often asking ourselves “Would I do the same thing in the same situation?” or “How would if feel if I could jump over a building like that?” or any sort of view reaction that places us inside the film. While this is a rich way to enjoy a film, even to think about it, it can also generate “shadow *ToMs” where we have not noticed that instead of trying to think of a *ToM on its own terms, we have taken residence inside it. This is a deployment of simulation theory (see the chapter on ToM) that corrupts the selection of *cultural contexts and *outcome statements of *interpretive projects. When we take up residence, we create a modified (shadow) *ToM that is less purely derived of the narrative and is instead some modification of our personal *ToM, clothed in a character that is embedded in a story. To the extent that we can avoid this, our chance for discovery and accurate interpretation is enhanced.

Finally, since I view identity as a socially derived object, that is, who we are is what others think we are and what we think others think we are, there is not real border between a cultural context and a ToM. Since we want to think about *worldviews and *values we separate the two but another way of thinking about this is simply “a ToM’s identity is the *status of relevant *cultural contexts.” In other words, to create a silly example, if one hates chestnuts and one discovers there is a secret society around the world of chestnut haters, part of one’s identity can very easily become “I am a member of the World Chestnut-Haters Association.” Or, conversely, if one wants to have the identity of being a member of a worldwide secret society, one can chose to hate chestnuts to gain legitimate membership.

…. And that leads to the most complicated portion of this line of thought: One’s identity is not enwrapped with the content of a cultural context, one’s identity is enwrapped in the content of a cultural context as one understands it. If one does not think you truly hate chestnuts that person will not consider you a member and your identity, to that person, is a “fake chestnut hater” whereas your identity is “full and legitimate member of secret society.” So, when we are positing cultural contexts and how ToM relate to them, for the sake of simplicity, we usually treat these contexts as floating independent of the way the ToM perceives it but in truth this is never the case and, in some situations, it is important to remember this.

In sum, one’s relationship to cultural contexts, as I will argue below, is a function of group membership and group membership is not just a part of identity but rather, is, identity. It is just that identity is not stable: depending on the perspective from which it is being considered (“how I, named X, think of myself” “how others think of person named X”) it can, probably does, change. We have limited ability to control how the way our identity resides in the minds of others.

17.4.6. Narrowly Defined Topic (NDT)

A *narrowly defined topic, together with the film selection, ToM determination, and wording of the *instance, completes the contract that individuals and groups will adhere to where carrying out interpretation. It identifies the topic that will be considered and is often in the form of a question and is, indeed, often in the form of a question with this pattern: “What is the *status of ….?”

The *narrowly defined topic supports a key assumption of the course: we all work with cultural blind spots and limits in our cultural knowledge and our best hope at noticing them or extending our knowledge is through dialogue. The *narrowly defined topic allows individuals to think about the same topic completely independently, then compare notes and thus, through the independent points of views, discover interpretive prejudices, failures and perhaps even dangerous “group-think” when everyone comes to the same conclusion.

Fashioning a good *narrowly defined topic is key to a successful interpretive project, but it is very difficult to achieve. Or, more precisely, the instance-NDT pair is difficult to create. One of these requires insight into locating a rich area of the film for successful bounded dialogue around issues relevant to the course. The required features of a *narrowly defined topic will be given in the next part of the book. I would only like to note here two things.

In terms of theory, it has long been recognized that how one frames an inquiry will have enormous impact on what the results of that inquire will looks like: bending meaning towards it, emphasizing certain things over others, entirely eliminating discursive space for other things, and so on. Please be aware how powerful, indeed, is the *narrowly defined topic you are fashioning.

The purpose of *narrowly defined topics is to set out a discursive space within which one can, through bounded dialogue, evaluate and discover something about the *status of *traditional *worldviews and *values. As such, it is a practical step in the process and must not resemble or invite, in any way, a thesis statement.

I have found that the composition of the *instance-*NDT pair is frequently a rich moment in the interpretive project that revealing the interpreter’s own *worldviews and *values as well as often reinforce *horizon’s of expectation rather than allow pathways beyond them. To be able to compose excellent *instance-*narrowly defined topic pairs is perhaps one of the best ways to assess whether a student has mastered the content of this course and has a basic understanding of the film for which the *narrowly defined topic is being written.

17.4.7. Cultural contexts: Defining a cultural context as descendant of premodern worldviews and values—Authoritative thought systems, fragments, and derivatives

When we are considering *traditional *thought systems such as Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism, it is too clumsy a tool to import all the various *worldviews and *values of the *system simply because one of its *worldviews or *values has been credibly identified. For example, even if I accept that all things change, it is not fair to say that I also subscribe to the Buddhist teaching that all aspects of the Universe are reflected in all other aspects of the Universe (the doctrine of co-dependence) even if, were I to follow the logic of my belief, I might need to accept this. The logic of the *system is not the point. As a living, breathing member of a culture I simply do not think about co-arising and you cannot predict my thoughts, feelings, or actions/reactions on something that I never think about.

On the other hand, if I learned that someone came up through the Catholic school system, I can reasonably take as an initial working assumption that the individual has probably been exposed to many of the doctrines of Catholicism and knows something about original sin, confession, and grace. In this case, the original *system is close and extensive and probably helpful for interpretation.

In this way we need to decide how much of an *authoritative system seems to be credibly relevant. When we interpret a *love narrative in film, to what degree do we need to reference the full teachings of an *authoritative thought system? This is a technical way of asking commonsense questions such as, “How important is Confucianism to someone living in Seoul who is twenty?” This is too general to be useful for focused discussion so we could create, for example, this *instance: “In the Korean film My Sassy Girl, Gyeon-woo often refuses to accept his mother’s efforts to find a good girl for him.” The *narrowly defined topic might be: “Is he being presented as a bad Confucian son or does the film seem to celebrate his independence, thereby dismissing Confucian *values?” Now we have something specific enough to generate a productive group discussion.

For the moment I would like to focus on the last word in the *narrowly defined topic: “*values.” There seem to be two *values at play and it seems reasonable to include both in our considerations: *xiao (filial piety, not as submitting to the authority of the parent but showing appreciation to the parent by being cooperative and receptive to suggestions), and respect for authority (one should obey one’s parents and at least show respect towards others higher in a hierarchy). So, should we stop there or should we make broader assertions that the whole of Confucianism is being called into question? It we just stay with these two *values, we are treating them as *fragments because they are indeed identifiably part of Confucian *values and Gyeon-woo, our *ToM, (and movie viewers) are likely able to label them as such. But the entire environment of the film while relatively strong in a variety of Confucian *values, also makes room for, and supports, a range of *values that are distinctly not Confucian. My interpretation is that the film should be seen as taking up the question, “Is filial piety a good thing?” rather than the broader question, “Is Confucianism a good thing?” I think we can credibly say that the film answers the first question as: “Yes, filial piety is good. Mother does indeed know best.” It also suggests that: “Some aspects of Confucianism are indeed good but we need to make some distance from other aspects so that love can blossom in a modern and satisfying way.” Ultimately, in my opinion, My Sassy Girl, is a film with conservative Confucian *values but reduces the oppressive feel of the Confucian *system in is full weight by also asserting the beauty of considering the individual as sometimes more important than the group. In this way, treating filial piety as a *fragment of Confucianism is more useful than asking the sweeping question, “Does My Sassy Girl support Confucianism?”

In our modern films, *fragments are far more frequent than full-fledged *authoritative thought systems, but reference back to the original *system can add precision to our understanding of the *fragment. And, of course, if we are reading a premodern text from, say, 14th-century Japan, we should take seriously the possibility that Buddhism is present (to the *ToM) in its full and broad scope as an *authoritative system.

On the other hand, 3-Iron ends with a stock phrase: “It’s hard to tell whether the world we live in is a reality or a dream.” Movie-viewers will most likely find this to be a familiar-feeling phrase because many versions of it appear in various places at various times. But some might say it is a Buddhist phrase. Others might say it is a Daoist phrase. Others might just nod, feeling it is “wise” but having no sense of its source.

One can argue that the source is the ancient philosophy Zhuang zi (later considered to be a Daoist):

Once, Zhuang Zhou dreamed he was a butterfly, a butterfly flitting and fluttering about, happy with himself and doing as he pleased. He didn’t know that he was Zhuang Zhou. Suddenly he woke up and there he was, solid and unmistakable Zhuang Zhou. But he didn’t know if he was Zhuang Zhou who had dreamt he was a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming that he was Zhuang Zhou. Between Zhuang Zhou and the butterfly there must be some distinction! This is called the Transformation of Things.[3]

But one could argue that the source is some stock wisdom floating around in premodern Korea and Japan as evidenced in this 9th-century Japanese love poem:

Was it that you came to me?

Was it that I went to you?

Was it a dream? Was it real?

Was I sleeping? Was I awake?”[4]

The only relevant answer to this question is how does the director of 3-Iron think of this concept and/or what does he expect his audience to think of it?

I would like to argue that the answer has nothing to do with either Buddhism or Daoism but is rather:

True love happens in a dream-space.

If this is correct, then the phrase is a *derivative: it is less meaningful to see it as Daoist or Buddhist as it is to see it as a common cultural position that “dreaminess is the place of pure emotions” or something along those lines.

I hope you can see how whether or not to position an object inside an *authoritative system, or position it as a descendant of the *system where recalling the *system helps understand it (a *fragment), or conclude that knowing the origins might be interesting in some ways but it is not directly relevant to an accurate understanding of the *ToM (a *derivative) is a matter of opinion and depends on your larger interpretations of the narrative. For example, imagine that I re-watch 3-Iron and begin to notice references to Buddhism everywhere. I might in that case rethink my conclusion and treat the last words of the film as a *fragment of Buddhism, not a *derivative, and will suggest that the Buddhist teaching “this is a world of illusion, which means this is a world of suffering” is relevant. Small changes like this can cascade through interpretations in much larger ways: if I make that assertion, the end of the film is also more depressing.

In sum, the content of the *cultural context we are considering expands or contracts depending on where we place it on the below spectrum—plotting something near the *authoritative thought systems requires that we think of more elements of that *system. Further, the farther to the left we plot an object the more *robust it tends to be as a result of the weight of its institutional constitution and theoretical / ideological power as a fully recognized *system.

17.4.8. Cultural contexts: ToM perspective, group representation

17.4.8.1. Cultural context from the perspective of ToM

When we begin to define the content of a cultural context, we do not ask a regional or historical question such as “What is a prominent or representative or definitely present *worldview or *value that we can associate with the time and setting of the narrative? Instead, our search travels in a specific direction: From the perspective of the *ToM, what might be relevant *worldviews and *values and how are those represented to the *ToM via groups?

Thus, we do not take an omniscient perspective such as, should the setting of the narrative be the American Deep /south, “one should remember and respect the Confederacy.” Instead, one says “Social Worldview: *ToM holds as a *worldview that there remain two United States—the Union and the Confederacy. These two nations still exist even if victory was with the Union and even if it appears that the Confederacy is gone.” In other words, we are not in the business of describing cultural contexts that empirically exist but rather contexts that the ToM believes exists.

17.4.8.2. Cultural context as represented by social groups

As indicated by the second half of the above statement about our search direction (“What is a prominent …”), when possible we articulate the *context-to-ToM relationship in terms of a cultural group-ToM relationship. That is, rather than think of *ToM relating to an abstract idea, we give that abstract idea a social body, a group, of some sort. The puts the analysis in line with the assumption that the context-ToM relationship is essentially one of identity and identity is essentially the function of how one thinks others think of oneself. Cultural contexts may indeed be highly abstract and only have an imagining group, such as when a ToM believes itself to be immortal (a member of a special elite of Daoist superiors of have attained immortality) or a “warrior of God” and, at the other end, contexts may indeed have empirical groups representing them, such as the Red Guards of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. That being said, most fall somewhere in between. The full spectrum should be kept in mind, as well as the theoretical possibility that there is no group at all. Keeping the spectrum in mind encourages discovery. However, stepping away from the view that cultural is represented to individuals through groups—even if the group is abstract, ill- or weakly-formed, or transient—is stepping outside the framework of the *course method, even if justified at the level of theory or for other analytic purposes. For the purposes of the course, culture is visualized as raising issues of identity and issues of identity are visualized as being resolved through the social being of the *ToM. In the case of this approach, culture is a non-entity if it is not associated with some sort of group. Groups by the way can be very small (Berkeley first year students from southern California, for example) or very big (all humans across time) and, as already state, real, ideal or just imagined in some way. They can even be provisional (“What if there is, was, or will be a group that believes …”).

17.4.8.3. Cultural context as represented by social groups but still called “contexts” not “groups”

Even with the above theoretical positions, I still wish to call a *cultural context a “context” not a “group” for several reasons.

First, the group itself will think of its *worldview or *value as something beyond it, perhaps even with metaphysical existence.

Second, “context” embeds the *ToM in the *cultural context which is closer to how ToM thinks of it, rather than a part of its imagined identity. The ToM views a *value as something that it cannot change (interact with) but only accept, modify or reject. If the term were group it raises the (what I think is false) expectation that perhaps the ToM thinks it has the power to alter a value since it is human(s) rather than an idea.

Third, “context” evokes somewhat better the possibility of a web of *values that, as a total effect, generate culture which might be closer to an accurate description of the ontology of *cultural than an emergent phenomenon associated with the interaction of many groups. But perhaps both of these are true. It is not entirely clear. However, the theoretical point does not have much governance over the playing out of an interpretive project so, for these other reasons, I prefer to stay with the word “context.”

There is no reason that a *cultural context cannot have intermittent or contradictory existence during the course of a narrative. It is for this reason that we tie a *cultural context to an *instance. We ask the question of *status about a particular *instance rather than giving a full description of the fluctuation of *status. That being said, since the significance of an *instance is derived from the larger narrative, it follows that the significance of the *status does as well. We reduce complexity by tying it to an *instance but it we do this too fervently, we lose sight of the bigger picture and the analysis begins to diminish in value.

17.4.9. Context-to-ToM relationship (“distance”)

17.4.9.1. Context arrays + context robustness

A description of the relationship between a *ToM and *context of course includes the refined content of the *context, as just considered above. It also includes a measure of the *distance between the *context and the *ToM. That *distance is a result of a dynamic combination of the *robustness of the *context, on one side, and the *receptivity of the *ToM, on the other.

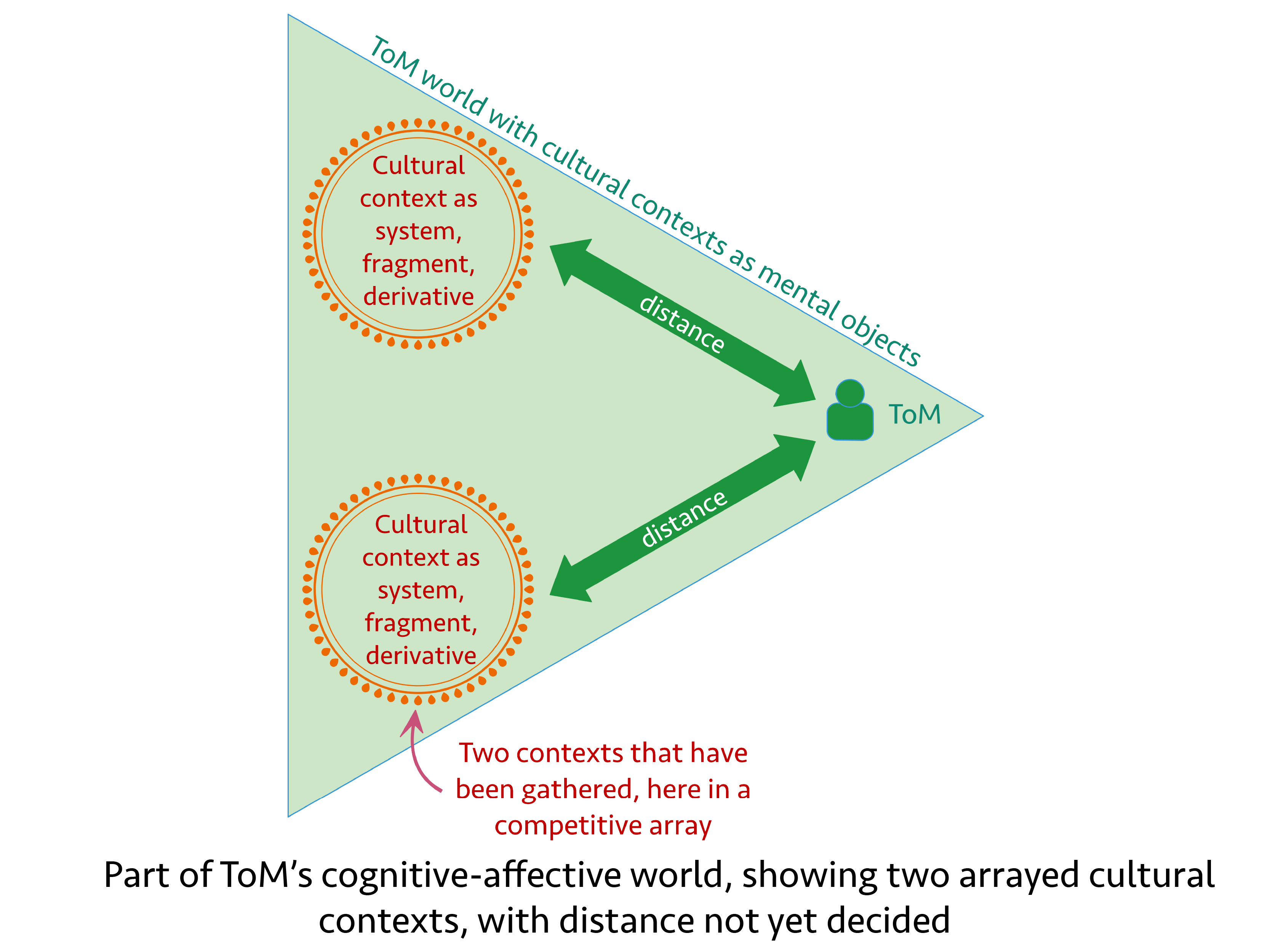

However, since *contexts exist in a plural environment, the way the interpreter *arrays the multiple *contexts influences this *distance. *Contexts in competition for the attention of the *ToM might have greater “*distance” than those that are sequentially present.

One might feel the full force of one’s parents’ cultural worlds when at home for the holidays whereas if one is sitting with one’s friends while on the phone to one’s parents the impact of the parental cultural viewpoints might be less. “*Distance” is ultimately an internal representation of the context within the *ToM but its empirical (figuratively speaking, that is, “empirical” within the world of the narrative) conditions are not to be ignored: When one is on the phone with one’s parents with friends nearby the impact of the parent’s world might be less because of one’s consciousness of one’s friends and the *values they embrace. On the other hand, if one’s parents are especially important to one’s way of thinking, one might be less conscious of the empirical presence of the friends when on the phone. Conversely, when visiting at home one might “bring one’s friends along” in one’s mind as a way to gain mental support for ways of thinking different than those of one’s parents. In this way, the *array of *cultural contexts is a hybrid result of actual presence-absence factors and mental presence-absence factors.

For our interpretations, we not only collect *contexts but *array them according to our interpretation and construction of the narrative world. As outlined earlier, *contexts might be discretely present (*autonomous), in competition with one another in simple or complex ways, sequentially present-absent, or *layered. A *ToM may or may not be fully aware of the *array configuration—it is common to encounter *ToM that just seem confused and undecided.

*Robustness refers to how forcefully or fully present the *system, *fragment or *derivative is to the *ToM. If I know that some people on campus carry concealed guns, those guns are weakly present to me. If I encounter someone pointing a gun at my face, the gun is fully, *robustly present. This is what I am calling “*robustness” and it is meant to indicate how fully and significantly present a *cultural context is. Again, this is “*robustness” as understood and experienced by the *ToM: If the *ToM is very fearful of guns, once it hears that some on campus are carrying them perhaps it worries about this all the time. In such a case, the guns are indeed *robustly present to the *ToM even if the reader, even many readers, even the *model reader would say that concealed guns are not something worth worrying about.

It is not really possible to offer a list of factors that add up to the *robustness of a *context because it is complex, highly situational, and truly a matter of judgment, often based on thin evidence. For example, as I sit writing this sentence, Catholicism is not *robustly present to me. However, when I visited the Pantheon in Rome and sat under its majestic dome, I felt a reverence for the Catholic Church, and its power, and most definitely its presence was very *robust.

However, even if we cannot generate a check list of factors, the *robustness of the *system as an institution and the degree that you are in an environment that embraces that *system (its *robustness to others, not the *ToM) are two things that often need to be considered. Narrative *status is another. We will discuss *status shortly.

17.4.9.2. ToM receptivity

The *robustness of the *context is very important. However, the degree to which the *ToM is or is not interested in or engaged with the *context is also clearly important. It is this combination—*robustness to one side (with considerations of *arrays in mind) and *receptivity to the other—that offer a dynamic picture of the *distance between *context and *ToM. We should keep in mind, of course, that this can and probably does change over the developments of the narrative. (Narratives, in part, are the telling of changes in this dynamic.) However, since we limit our investigation to an *instance, we are not compelled to measure and re-measure this distance for each step of a story’s progress.

*Receptivity, the word itself, suggests a passive ToM and so, in this way, is unfortunately misleading. “Affinity-receptivity” were it not such a mouthful of a word, be a better term for indicating a ToM’s positive movement toward a cultural group, on the one hand, or, on the other, its willingness to allow the insistence of the cultural group to inform its thoughts, feelings, and actions. It works both ways. Further, in terms of the passive receptivity, this can be the result of something in the nature of the group itself or a third factor such as a ToM that upholds a more general principle such as “the *values of a group should be upheld whenever possible.” In this case it is not the content of the groups *values but simply that it is a group, which becomes the deciding factor.

Therefore, one leading factor in *receptivity is the degree of allegiance of the *ToM to the group belonging to the context. If that *ToM sees itself as a member, and wants to remain so, the *values of the group have greater persuasive power than if that *ToM feels little toward the group or is considering leaving the group.

Similarly, another factor that often deserves attention is the degree to which the *ToM follows the cues of its environment or, instead, tends to be a “loner” in this regard. As a general working rule in our *East Asian narratives, the impulse to accede to social requirements to uphold social order tends to be reasonably strong, but that does not mean that they are always strong. It is just a reasonable analytic start point.

As with *robustness, there is no fixed list of factors to add up that would result in some precise measure of *receptivity.

Here is an overview of the basics considerations in deciding context-to-Tom *distance:”

17.4.10. Describing via spectrums status and topical intensity

*Status refers to a spectrum where at one end of the spectrum a *worldview or *value is accepted and at the other, rejected. The mid-range represents ambiguous territory.

*Status resides at multiple levels. The key levels are *ToM, narrative world, and author / director world. There are others.

Statements about *status are presented together with statements on *topical intensity. In usual cases of analysis, thought is clustered around important elements of the object. That it is being discussed in analysis implies that it is an important element for the object. However, since we are interested less in the object than the *worldview or *value that is contained within it, “faintly” present *values can be interesting to us. The *topical intensity spectrum makes space for us, permits us, to talk about things that are not very central to the object in the big picture but have something interesting to say about the *status of a certain *worldview or *value.

It should be noted that middle ground here needs some careful consideration before deciding that a *value falls into it. If I can’t decide whether or not to pick up and keep the $100 bill that someone in front me just dropped but is unaware that he dropped it, that is not a middle group *status. It is clear that I should tell the person he dropped money. That I hesitate does not weaken the *value itself; in fact, my moment of indecision is probably a narrative moment that further strengthens its affirmed *status. There is a middle ground on the spectrum where it is unclear exactly where the *ToM or narrative stands, or when the position is overtly in conflict, or when the ToM seems to switch back and forth, or when the *worldview or *value seems to have been edited, amended, mixed, or otherwise altered for some reason.

It is common that there is *status clarity as to *worldviews and *values, even if they are in conflict and competing with one another. This is part of what make narratives accessible and compelling. Here is an example of two *values both having the *status as affirmed, that are in conflict. A crowd is throwing stones at a dog. Our *ToM, Maddie, is trying to decide whether to follow the *common practice of the crowd and thrown stones at the dog or to uphold her personal *value of not hurting animals. It is not that there is lack of clarity and that we should consider the *status as somewhere between affirmation and rejection. On the contrary, it is quite clear: the crowd wants Maddie to join in the stoning and Maddie, personally, does not wish to. These are two *values, both clearly expressed in the narrative. If Maddie resists the crowd and is later rewarded for that resistance in some way in the course of the narrative, the *status of “don’t throw stones at dogs” as a *value is affirmed at the level of the narrative. The narrative position and Maddie’s position are aligned. Narrative progress or outcome is one of several ways to deduce *ToM *status, when used carefully. But, to further pursue the example: If later in the narrative Maddie needs the help of the crowd for something—let’s imagine that she is hanging of the edge of a cliff and hopes for a helping hand—and the crowd does not even notice her plight, then perhaps we can say that at the narrative level “putting your own views ahead of those of the group” is being partially or fully rejected. If Maddie is presented as a sympathetic figure and we viewers are sorry that she will fall and die, Maddie’s *value, which is also probably the *value of the director and viewers, has not been rejected, of course. But if Maddie has been presented consistently and unsympathetically as a stubborn fool and the dog was one that had attacked and killed a child and was rabid, then, yes, perhaps the *status of “standing by your dog principle even when the group says otherwise” is being actively challenged.

In this way, *status appears at multiple levels in a narrative: whether a *narrative figure accepts or rejects a *value, whether the narrative world seems to suggest that the view is, generally, accepted or rejected, whether the author or director seems to agree with the views of her or his own narrative, and, finally, whether the *model reader or viewer accepts or rejects it. Clearly, we are in the world of speculation. But it is relevant and interesting speculation, and is necessary for conclusions, and is not as arbitrary as it might seem.

In addition to a affirmation-conflicted-rejection spectrum, we also need to consider how important the topic seems to be to the *ToM or narrative in general. I will call this “*topical intensity.” This means “the degree to which a topic is actively engaged by the narrative,” not “superficial intensity.”

*Worldviews tend to have very low *topical intensity because they are widely adopted by all members of the object of analysis: the *ToM, the other characters, the narrative perspective, the author / director, and the reader / viewers. They do not bear mention. For example: “I will now make this incredible leap from one rooftop to the next. You should feel worried because there is such a thing as gravity that might pull me down. But you should not feel too worried because I am the hero of the film and it is too early (probably) for me to die. We are only 5 minutes into the film after all. …” We don’t encounter film dialogue like this because all of the comments are part of a *worldview that we expect. So, low *topical intensity can be (but is not necessarily) an indication of *worldviews and *values so completely accepted that they do not need prominent mention in a narrative, or any mention. As earlier argued, if a narrative does not “make sense” it might be because the assumption of shared *worldviews or *values is off-target.

We can plot the *status spectrum horizontally and the *topical intensity spectrum vertically as follows:

Plotting in this way implies, correctly, that the *topical intensity and *status spectrums are independent with a large range of possible combinations. It also depicts how the two combine dynamically, giving a full picture of the interpretive relevance of *status.

Formulaic Hollywood films that noisily affirm “family values” which everyone already agrees to, could be plotted near the red number “1” on this chart. *Worldviews and *values that both the writer and viewer agree to (probably even unconsciously), and so it never occurs to anyone to bother to articulate them (there is no need to do so) could be plotted near the red number “2.” “Radical” art that strongly challenges a *value would be near the red number “3.” Finally, what we might be tempted to call “timid” art that just lightly suggests resistance to a *value might be near the red number “4.”

We encounter tension between narrative characters when the two of them would plot a certain *value at different locations either in terms of whether or not to affirm it or simply whether or not it is important to think about it. We can also find dissonance across levels. For example, if viewers would plot a *value differently than the director, that director might be widely described as “controversial.”

17.4.11. Outcomes: individual and group

Outcomes are simple, one sentence statements that answer or otherwise respond to the *narrowly defined topic. Sometimes, beneath this single statement will be a more extended explanation of it.

I require that outcomes be compact and single-parted (avoiding “X and Y” constructions, for example). This requirement is to constraint the interpreter to a specific position (which she or he may or may not be comfortable with), not for the purposes of achieving final, firm conclusions but rather so that there is a clear statement around which a debate or further thinking can occur. For this reason, I try to avoid using the phrase “interpretive project conclusion” since outcomes are more like start points for further thinking.

Outcomes are entangled in the fashioning of *cultural contexts and their relationship to the *ToM. Often the outcome is a description of what seems to be in the narrative (as *ToM content), with the *cultural context found and fashioned in order to explain the intuitive sense of plausibility of the outcome already decided upon. However, there is a high expectation that interpreters maintain the integrity of rethinking and discovery rather than fall into the trap of making a strong rhetorical argument to prove a point. Therefore, in the process of matching *cultural contexts to outcomes, often the outcome becomes less plausible and the interpreter begins to consider a fuller range of possible *cultural contexts in order to rethink the interpretation of the *ToM.

17.5. Reviewing elements of the interpretive project workflow via graphic representation

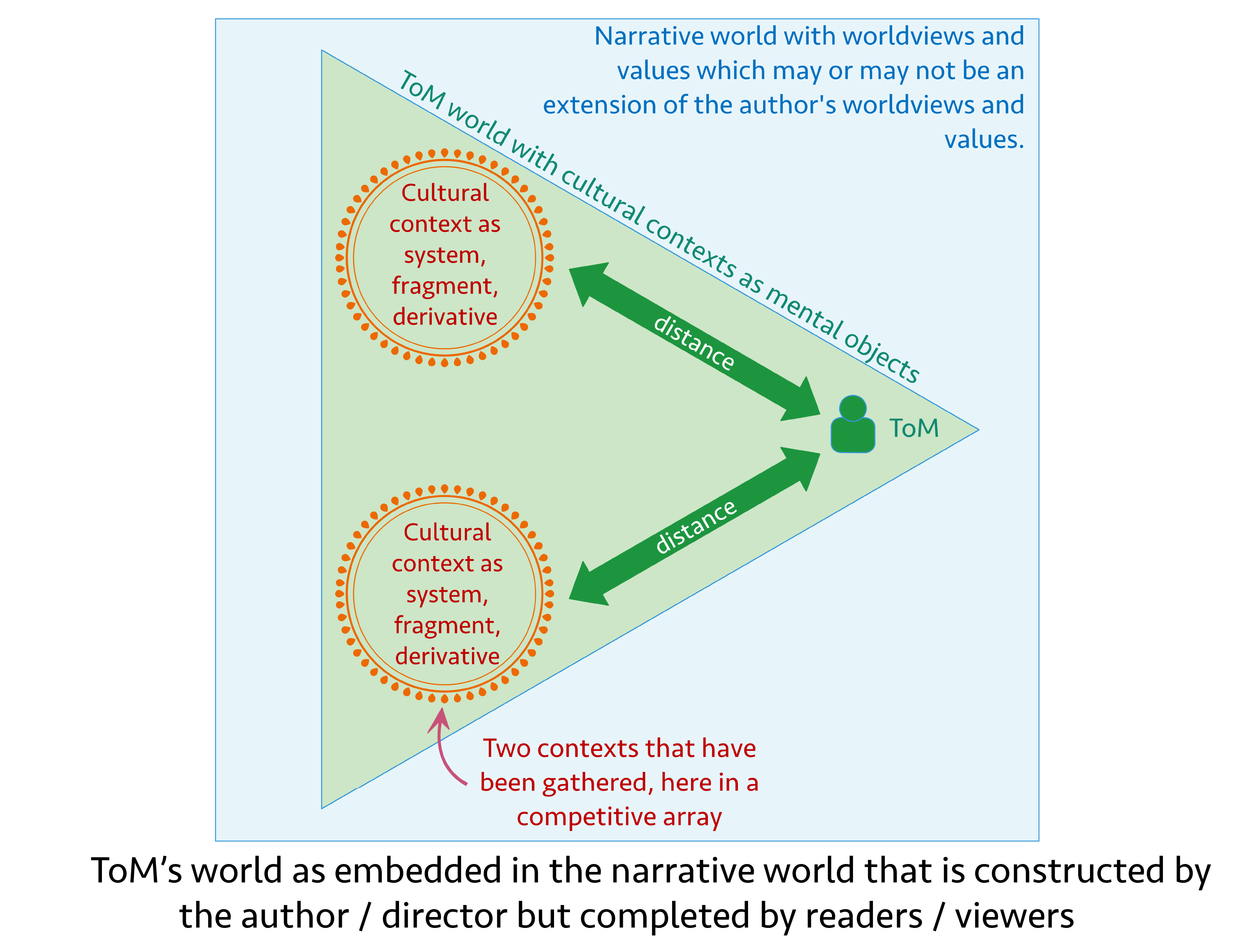

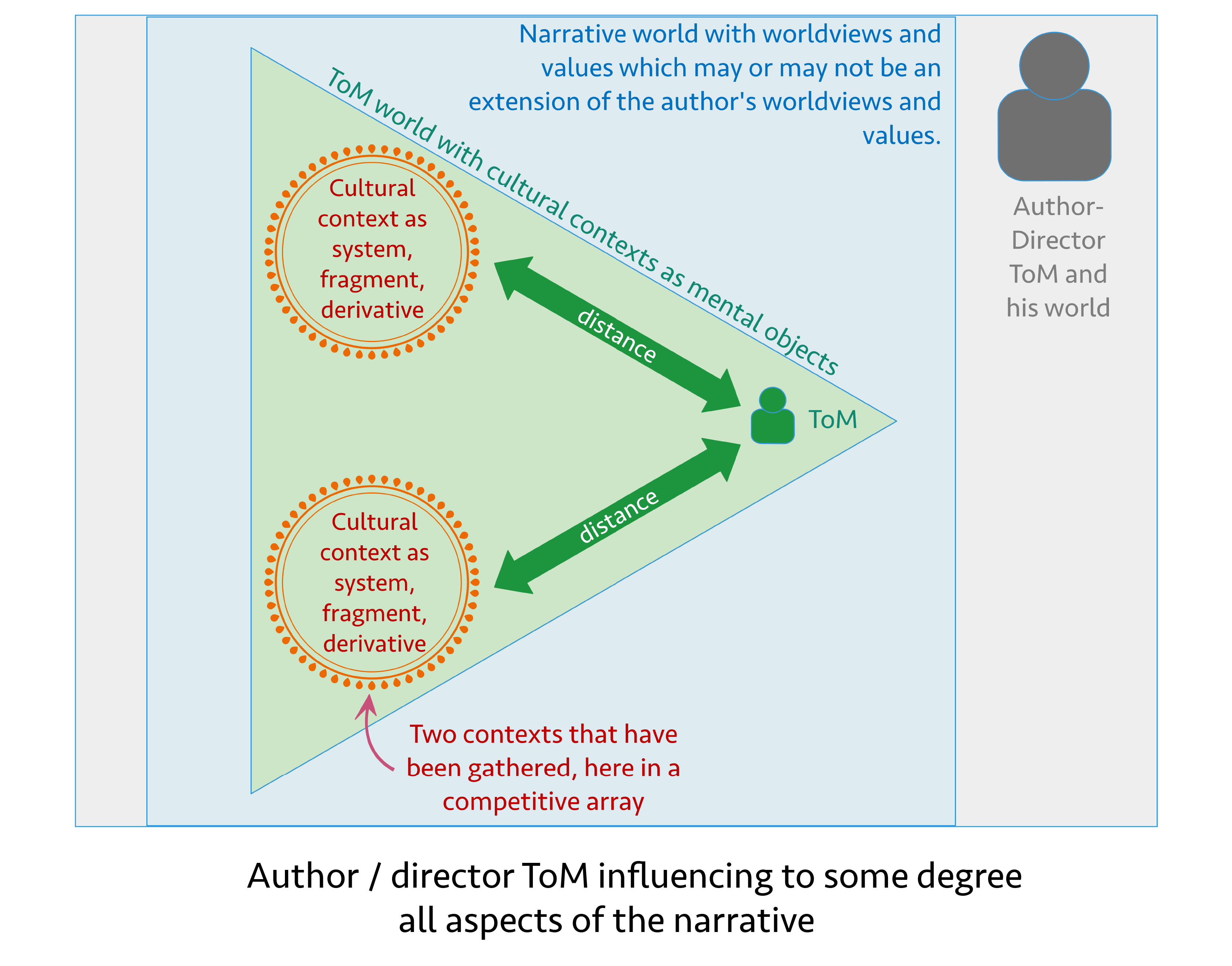

Let us reconsider through a series of graphics the three key facets of interpretation described in this chapter: refining *cultural contexts and *arraying them, deciding *distance (through *context *robustness and *ToM *receptivity), and *status / *topical intensity as it operates at multiple levels. While the graphic representations take up situations one at a time for the sake of clarity, in practice all of the above are being considered, adjusted, and balanced against one another more or less at the same time.

One aspect is to gather *cultural contexts—being generous and ambitious in the scope of the collection but ultimately limiting them to what is meaningful to the *ToM. One process of this limiting is to determine what is plausibly relevant. For example, perhaps not all of Buddhism (an *authoritative thought system) needs to be considered. Perhaps only a portion of it, a single idea associated with it (a *fragment) is all the really matters. Perhaps the cultural object (a *worldview or *value) truly stands on its own and now has little or nothing to do with Buddhism (a *derivative). In addition to refining content in this way, *cultural contexts should also be appropriately *arrayed. Gathering, refining, and *arraying are all done from the perspective of the *ToM, who, in this graphic, hovers off to the right as the point of reference. For the sake of accuracy, it should be noted that this is in fact two different states: an actual *ToM with actual *contexts with which she or he engages and a cognitive self-representation of him or herself “inside” her or his mind, a *ToM imagining her or himself, contemplating or sensing the presence of *cultural contexts. I have not complicated by the graphic to represent this dual state of things.

Having refined the content of the contexts and decided how they *array in their relationships to the *ToM, we are in a better position to decide how relevant the *context is by settling on a credible *context-to-*ToM distance, a technical way of expressing things such as “Honest seems really important to him” (a short distance) or “If he had to choose between an easy life in a beach house or marrying her, he is going to drop the beech idea and go for the marriage …. but he is never going to forget that he gave up one for the other” (two competing *values at nearly the same distance) or “Although all her friends see the world as a cold and competitive place, her grandmother always told her that kindness should be put first and it seems that this is her guiding principle” (two competing *values with the grandmother’s cultural world at the shorter distance).

However, we need to remember that we are not talking about the real world. We are making interpretations of a world that has been constructed through a joint effort of the author / director on the one hand and the reader / viewer on the other. Whatever that world turns out to be, it strongly influences how we should consider the *ToM in multiple ways. In any event, we need a clear picture of this world, otherwise our *ToM analysis is flawed, perhaps extremely flawed, at the level of method.

And, finally, just as a *ToM inhabits the world of the narrative (no matter how it ends up being constructed), the *worldviews and *values of that narrated world may or may not be the same as that of the author / director. It is very likely that the best interpretations have explored the similarities and differences between the author / director and the world that she or he has invented. It should be noted for the sake of accuracy, however, that this is our understanding of the author / director’s world. We may or may not be well aligned with her or his own understanding of it. Sometimes this matters, other times it does not. Regardless, the graphic simply reminds us that the author / director’s world embraces everything else:

- FN: You might recall that one of the large unsettled issues that subverts the premises of the *course method is whether knowledge is derived from principles or simply memorized patterns and how we make decisions. See the discussion of *Connectionism and *Connectivism. ↵

- If you are interested in algorithmic-driven literary criticism, here is an article that uses differential equations to model love narratives: Mikhail E. Zhuravlev, et al., "What Issues of Literary Analysis Can Differential Equations Clarify?" International Journal of Applied Evolutionary Computation (IJAEC) 6, no. 3 (2015), accessed February 22, 2018, https://www.igi-global.com/article/what-issues-of-literary-analysis-can-differential-equations-clarify/136069. ↵

- Burton Watson, trans., Zhuangzi: Basic Writings (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003), 44. ↵

- Japanese poems new and old (Kokin waka shu), no. 645, based on Tales of Ise, episode 69. ↵