Book of Changes ◆ yang-yin and its ramifications ◆ five elements (wuxing) ◆ Daoist passivity and change ◆ Daoist sexual alchemy

Key terms introduced in this chapter:

- wuxing

- yang-yin

Key terms mentioned in this chapter that should now be familiar:

- cosmic worldview

- cultural contexts

- East Asian

- layers

- pluralities

- values

- worldviews

- wuwei

28.1. “Ancient Chinese cosmology” (Book of Changes)

By “ancient Chinese cosmology” I mean those very early constructions of the nature of the cosmos that become entwined with Daoism and which Confucianism implicitly accepts. Although much of these ways of thinking were fully incorporated into Daoism and would be, now, considered as Daoist ideas, they did not develop inside an authoritative thought system we could call Daoism. It is more accurate to view their roots as in the Book of Changes (Yijing).

28.1.1. A cosmos of shared essence, ever in change, and built for a masculine / feminine polarity

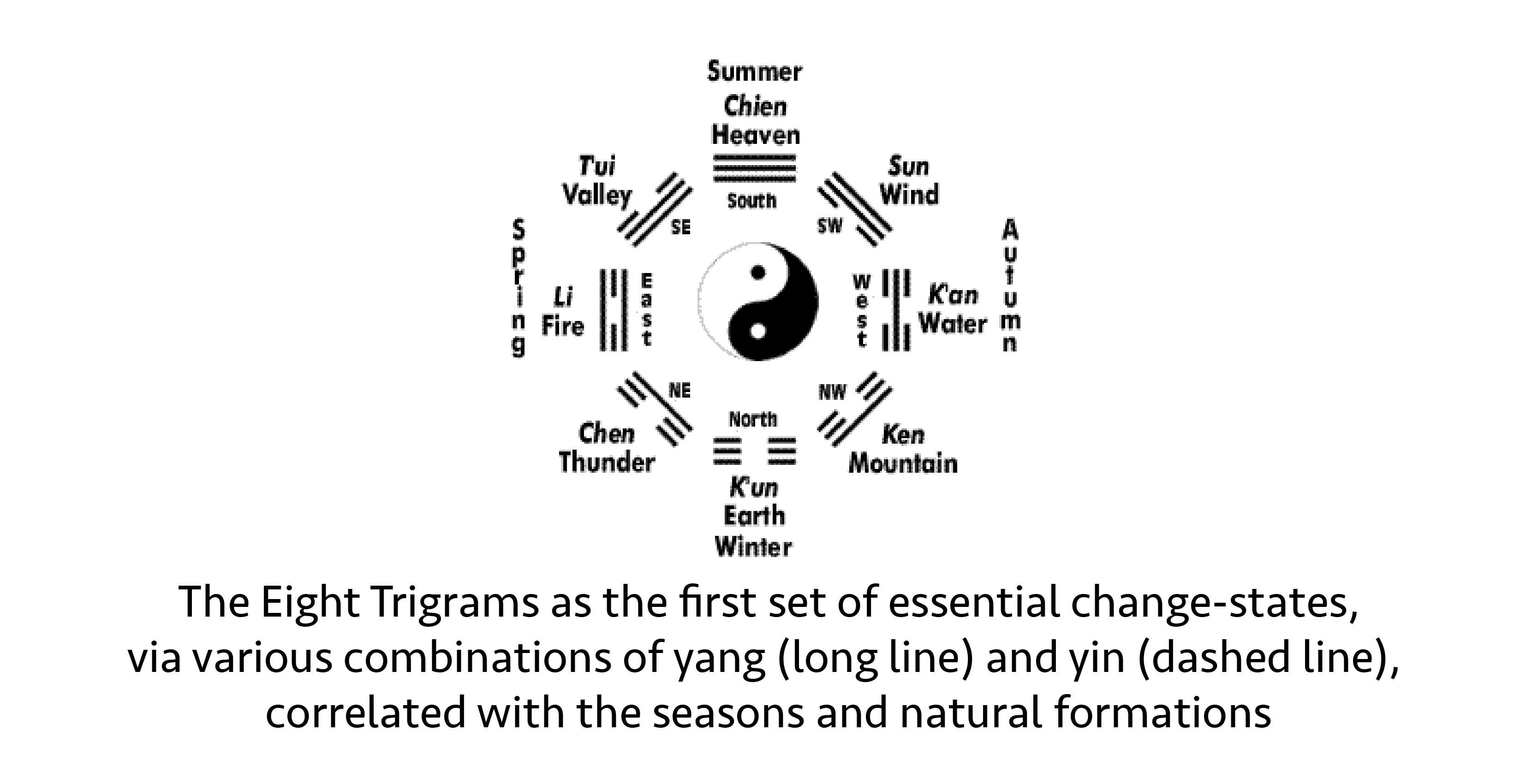

In this ancient system, the universe comes into being as the separation of chaotic cosmic energy into two basic qualities: yang (the hard, assertive, bright, active and masculine) and yin (the soft, yielding, dark, passive and feminine):[1]

According to ancient Chinese metaphysics, as recorded some 4000 years ago in I ching [Yijing] or the Book of Changes (Wilhelm translation, 1967), when the undifferentiated universe (symbolized by an empty circle) moved, light or Yang was produced; when movement ceased, dark or Yin appeared. The continuous interplay between these primal bipolar forces of Yang and Yin (symbolized by a circle of interwound white and black segments) creates stress, change, and harmony in the universe as humans know it. At the beginning of the Great Commentary on I Ching [Dazhuan, before 168 BCE], attributed to Confucius, we find the following (Wilhelm, 280-86): “Heaven is high, the earth is low; thus the Creative and the Receptive are determined. In correspondence with this difference between low and high, inferior and superior places are established. Movement and rest have their definite laws; according to these, firm and yielding lines are differentiated … The way of the Creative brings about the male; the way of the Receptive brings about the female.” The underlying polarity of Yang and Yin thus begins with light vs. dark and extends not only into high vs. low, creative vs. receptive, firm vs. yielding, moving vs. resting, and masculine vs. feminine, but also into many other areas of human concern, including the sun and the moon, the weather, the parts of the body, and even the distinction between gods (all Yang) and ghosts (all Yin). This polarity is not simply evaluative; it is rather, as Wilhelm (297) concludes, a polarity between two global forces which can only be termed THE POSITIVE AND THE NEGATIVE.[2]

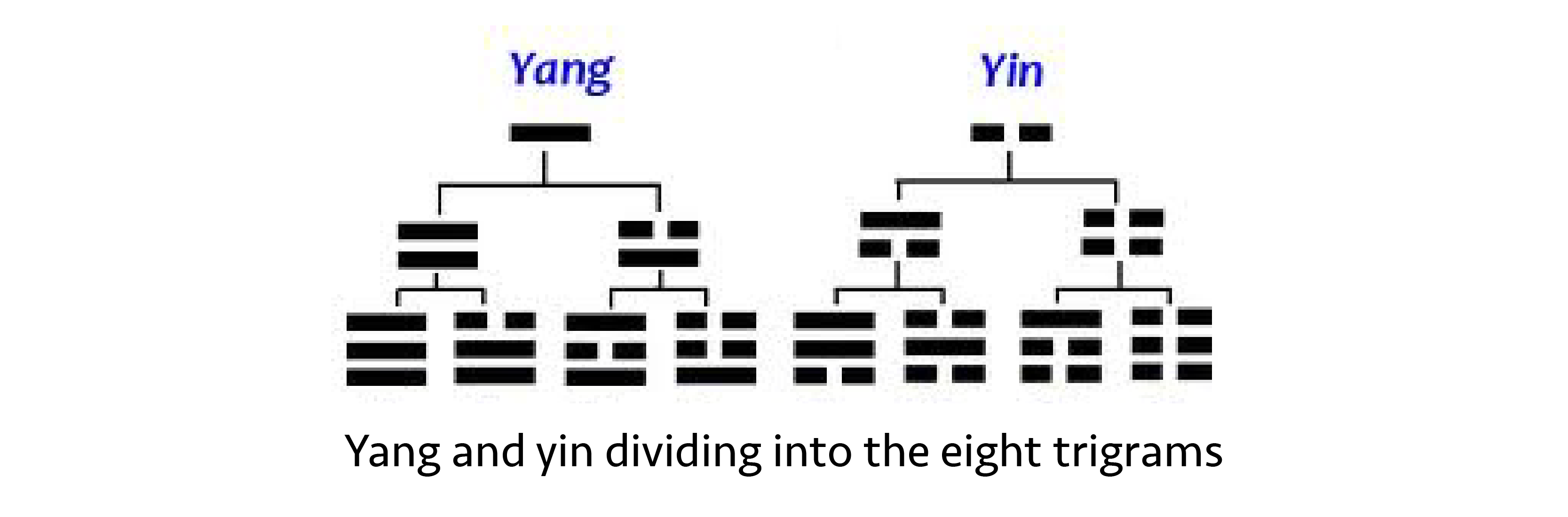

Yang and yin continue to divide numerologically into the eight trigrams and then the sixty-four hexagrams. These sixty-four represent states with various mixes of yang and yin as they transition the next phase.

While there are sixty-four different basic states, all are determined by combinations of yang and yin. This is the basis for three concepts important for our understanding of *East Asian *worldviews and *values.

28.1.1.1. Eternal, natural change

The first concept is that all states are in flux, in transition to the next state. Ancient Chinese cosmology posits as universe in constant, eternal, ever-refreshing change. There is no entropy in this system. Change is natural and healthy.

28.1.1.2. A universe based on harmony, balance and the Golden Mean

The second concept is that yang and yin both derive from the same original cosmic force. That is, they are not good and evil in opposition, each of different essence with the potential of one overwhelming the other. There will always be yang, there will always be yin — the state of affairs is coexistent either in balance or out-of-balance as the case may be. “Truth” — if it should be called that — is not an absolute good but a process of ever-changing mixes of yang and yin.[3]

According to this *cosmic worldview, conflict resolution seeks a proper balance of forces rather than an elimination of unwanted forces. Of course, if the kitchen sink has been attacked by ants, zapping all of them is the solution, rather than leaving an appropriate number to coexist and tolerating a few ant lines. But in an unhappy marriage, an accommodation of your partner’s displeasure might be all you can hope for in the situation rather than eliminating or reversing it. The *Golden Mean—balance in terms of one’s emotions (poise, stillness), non-excessive behavior, avoiding aggressively assertive behavior that might cause a backlash, all these sorts of “wise” approaches to life’s challenges are grounded in these very old ideas that opposing forces are nearly always present in any given situation and all situations are in a state of transition to the next state, not static. In the endless challenges that arise in love relationships, we very often see behavior choices based on this *worldview.

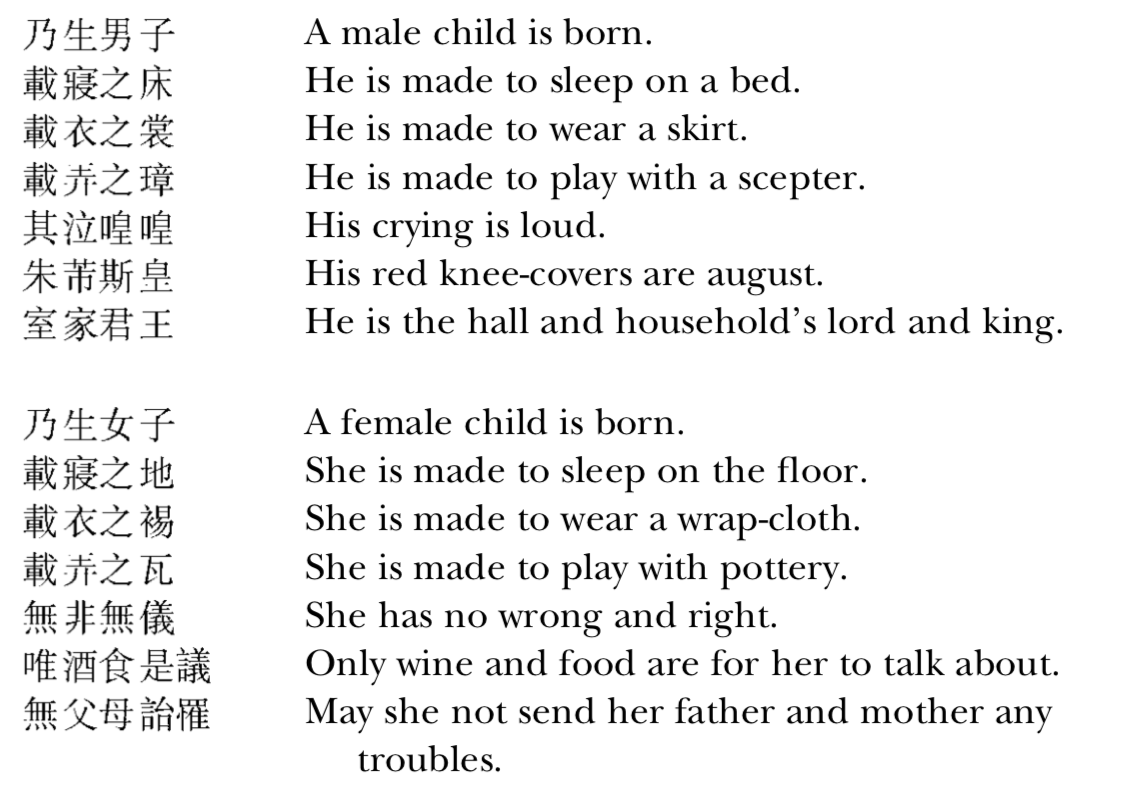

28.1.1.3. Phallocentrism

The third important aspect of this, for our purposes, is that it is a *worldview that leads quickly to gendered descriptions—according to this system, there is such a thing as manliness and womanliness at the metaphysical level. This is a very high-level status to give to gender differences—it makes it a truth that cannot be altered or ignored. This view more or less locks men and women into stereotyped expectations as to what is proper behavior and grants men freedom to be active and restricts action for women. In other words, sexism is encoded into this system. Confucianism, with is emphasis on social hierarchies further encodes this sexism, placing the male in the superior position. As a simple example, here is poem from the Shi-jing (Classic of Poetry, 11th to 7th centuries BCE) as quoted in The Culture of Sex in Ancient China [4]:

Ode 189, Shi-jing (Classic of Poetry, 11th to 7th centuries BCE)

That being said, the yang-yin system grants yin an essential place in the making and maintenance of the cosmos and recognizes the value of yielding and retreating forces. This will support *ethical principles that value patience, waiting and “non-action” (*wuwei).

28.1.2. The power of the hidden

This concept was first introduced in the chapter of *pluralities in the discussion of various arrays of *cultural contexts, in particular *layered *cultural contexts.

The second important aspect is the assertion that the seed of change for the next state is hidden within the current state. If you look at the classic representation of yang-yin you can see how there is always a bit of yin in yang and a bit of yang in yin. “Pure” states of yang and yin are considered unstable and brief as the energies are far out of balance and the cosmos evolves not towards entropy but towards balanced, fluid, endless change.

As a practical effect, this means placing a high value on the occulted or hidden as powerful, as a force to be attentive to.

- Just because your partner is silent does not mean that you should not fear the anger hidden within.

- Love can sneak up on you as a tiny seed growing in your heart that at first you do not notice.

- Your relationship is beginning to fall apart and you know this because that little comment by your partner seems “somehow strange” and you know it is a glimmer of what is inside her or his mind, or inside the relationship itself.

- And so on.

28.1.3. Relational thinking versus oppositional thinking

Finally, this worldview argues that everything is originally of the same substance (before yang and yin separated from each other) and so rather than a world of good versus evil, it is a world of good vis-a-vis evil vis-a-vis good. The two can never really be separated. Rather than in opposition, things are in relation to each other: Love and hate are related; success and failure are related, and so on. In our narratives, this can create partial solutions, partial endings, semi-closures, ambiguous moral attitudes, and so on. The Western novel’s narrative arc of development-climax-resolution (closure) is often not present. Things feel unfinished or still in process.

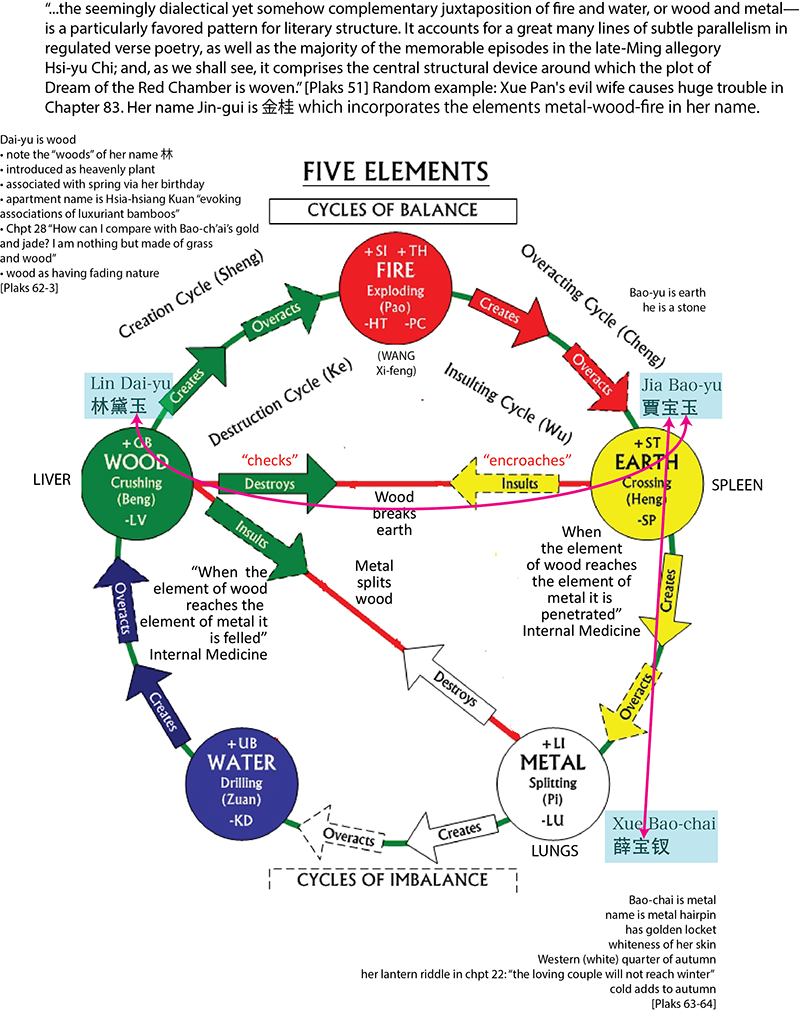

28.1.4. The five basic elements or movements (wuxing)

In addition to the basic explanation of how all things in the universe came into existence, what is their essence, and how things change, the universe is said to be impelled to move by five basic movements (五 行, wuxing): fire, earth, metal, water, wood. It is easy to locate diagrams of these relationships on the web. One of the simplest English-language descriptions I have come across is on a website that introduces T’ai chi.[5]

Finally, the cosmos is an orderly system of correspondences—the five elements are associated with five directions, five colors, five human organs, and so on. The basis of Chinese traditional medicine (CTM) is to recover natural circulation, counter-acting distorted energy exchanges that have arisen because an element is over- or under-active, or moving in the wrong direction.

But what is more interesting to us, perhaps is an idea that human interactions can also be understood as an interaction of these elements, offering a psychology entirely different from modern views of why humans behave the way they do. Here is a famous example from Story of the Stone (Dream of the Red Chamber), outlining how the three primary characters affect one another. This will not make much sense except to those who know the story but the basic idea it evident anyway.[6]

28.2. Daoism

By “Daoism” I do not mean its more recent formulation as an organized religion but rather the very ancient early principles of how the cosmos is designed, how change occurs via elemental forces, and the strong suggestion that it is healthy, even wise, to harmonize with the various configurations of the cosmos (“non-action” 無為, *wuwei) rather than insist on one’s own line of action (self-determination, exertion of will). These basic ideas have a huge influence on the content of Confucianism and Chinese (not Indian) Buddhism. (Korean and Japanese Buddhism derive from Chinese Buddhism, as no doubt you can guess.)

28.2.1. Passivity

Confucian and Buddhist principles are definitely more proximate to *East Asian values and strategies of action. Nevertheless, the very *East Asian idea that “some things are not to be” and it is better not to force the issue—in other words, it can be better to wait, yield, give up or otherwise be passive, waiting for the current unhelpful situation to change—is better attributed to Daoism that anything else.

28.2.2. Daoist healthy cyclical change and Buddhist change as suffering

Both Buddhism and Daoism embrace a worldview that asserts the cosmos, everything, is in constant change. However, their views of change are very different. Buddhism teaches that life is suffering because humans perceive change as painful. Further, constant change is the result of “emptiness”— all phenomenon are empty and therefore non-persistent. Daoism teaches that the cosmos is an orderly system of ever-renewing, ever-refreshing, healthy cycles of growth and decay. Buddhism seeks separation from an unhealthy psychological or emotional reaction to the truth of change, through wisdom. Daoism suggests that health is derived from harmonizing with endlessly changing situations and effectively working with the forces at hand.

28.3. Daoist sexual alchemy and early ideas about sexual activity

Because of the graphic nature of this particular discussion, I refer you to the online course materials in the folder on ancient East Asian sexuality. The brief statement of what is important to us here is that sexual intercourse is not considered to be part of expressions of tenderness or deep love. Instead, sexual intercourse is required of men for them to be healthy because intercourse is drawing energy from the woman into the man. Since, after intercourse, the woman’s energy is depleted, the man must sleep with a different partner (if he is to have intercourse again soon) to benefit from further energy”stealing.” Sexual intercourse, in other words, was a way of giving to a man vitality, or for a man taking it. He is how one scholar puts it:

Sex, like music, is considered something of a universal language, but anyone who has listened to Chinese music will tell you how different la différence can be. To Chinese sexual sensibilities, the Western sexual ideal—two souls striving to be one, who tune their instruments of the same pitch, make beautiful music together for a short duet, share the glory of a crashing crescendo, and console each other through a languorous denouement—is so much adolescent thrashing. How different the Chinese ideal, for here the male conductor rehearses each member of his female orchestra through the entire score, only to rest his baton as she reaches crescendo, absorbing the exhilarating waves of sound, before he retires to his dressing room to count the evening’s receipts.[7]

Daoist sexual alchemy was not widely practiced but these basic ideas found their way into early medical manuals used by doctors and the basic ideas are representative of premodern views of heterosexual activity probably across all of *East Asia.

28.4. A brief summary

What all of the above means to us is the generation of interpretive positions such as this: in love relationships is a tendency towards passivity when things are not going well and, probably somewhere deep inside, a lack of surprise that a relationship might change in its quality, or end. “Happily ever after” is not a plot line that seems credible in a Daoist (or Buddhist) context and it is the individual, not the romantic or married couple, who should harmonize with the cosmos. Daoism does not afford couples any special status in terms of spirituality, religiosity, or morality. It focuses on the individual growing in healthy power and wisdom to attain, ideally, immortality.

- While yang-yin is seen as a quintessentially Chinese way of thought, Evancovic makes an interesting argument that it originates in India. See, M. R. Evancovic, "What or who really is the Tao? The Aryan Vedic origin of Yang-ying (Skura-Krrna) philosophy of Taoism (Adhvacara)," Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute 92 (2011): 52-55, http://www.jstor.org.libproxy.berkeley.edu/stable/43941272. ↵

- Charles E. Osgood and Meredith Martin Richards, "From Yang and Yin to and or but," Language 49, no. 2 (1973): 380-412. doi:10.2307/412460.Osgood and Richards are exploring structures of cognition through linguistic, especially semiotic, analysis and they seek to show the complexities of bipolar thinking so the polarity here is a little overdrawn I think. ↵

- Manichaeism, which started in the Mesopotamian region in the third century and which spread quickly both eastward and westward, and survived in China for centuries, also posits a dualistic universe but one where good and evil are in constant conflict. ↵

- Paul Rakita Goldin, The Culture of Sex in Ancient China (University of Hawai'i Press, 2002), 24, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wqhd2. ↵

- I offer this link for the diagram itself. I am not endorsing the written description. "T'ai Chi – QiGong Florida," accessed March 10, 2018, https://taichiqigongflorida.wordpress.com/wuxing/. ↵

- This was first introduced in the chapter on mindreading and narratives. ↵

- Douglas Wile, The Art of the Bedchamber: The Chinese Sexual Yoga Classics Including Women's Solo Meditation Texts (New York: SUNY, 1992), 3. ↵