Implicit and cognitive bias ◆ mimetic desire ◆ attractors ◆ cultural attractors

— Terms —

- Introduced:

- cognitive attractors

- cultural attractors

- mimetic desire

- Mentioned and should now be familiar (review if necessary):

- patterns and models

- thoughts, feelings, and actions (TF/A)

— Chapter Abstract —

This chapter lists various patterns and their attributes that tend to bend interpretation in a particular direction beyond our conscious intentions and which can include cultural positions: subliminal priming, implicit bias, cognitive bias, prior interpretations, mimetic desire (selection of what is desirable based on others), and attractors (patterns towards interpretations drift).

— Chapter Outline —

- 8.1. The “gravitational power” of patterns, and some elephants

- 8.2. “Early decisions”—subliminal priming, biases

- 8.3. “Settled law”—the heavy influence of past interpretations

- 8.4. Interpretive decisions made for one by others: cultural membership, mimetic desire

- 8.5. Attractors

- 8.6. Cultural attractors

8.1. The “gravitational power” of patterns, and some elephants

“Gravitational power” as I am using it here is a metaphor for the invisible ability of some elements (*patterns but not just *patterns) to draw us towards or into certain interpretive conclusions, a scenario which stands in contrast to one where we consciously choose to arrive at an interpretation, which common sense suggests is the more usual process. Of course, we are aware that we make a number of decisions “unconsciously” and that how we see the world is affected by our cultural and more immediately personal identities, as well as the context of the situation. But I would suggest that we are wrong in our intuitive understanding that, if it matters, we can think something through with more care and objectivity and arrive at a sufficiently accurate interpretation. The argument I offer in this book is that we are far less free and “objective” than we think and that, if we are better informed of the processes of interpretation and develop different interpretive habits than those which come more naturally to us, we can indeed mitigate our cultural prejudices, biases, and blind spots and better “learn” another’s world, that is, the way someone else, and in particular someone else of a culture different from ours, is thinking.

I will detail below some of the key elements in interpretive conclusions but before doing so there are some “elephants in the room” that need naming.

To begin, it is our “hardwired” (neurological, not simply psychological or cognitive) tendency to be narcissistic in our interpretive perspective. This seems intuitively correct to us, based on our own experiences in life, but various studies have supported this view of self. One I find particularly intriguing is the ability to notice our name mentioned in complex stimulus environments even when we are not anticipating it.[1]. This tendency 1) affects selection in the SO/M process since we are most interested in what seems relevant to us, and 2) strongly predisposes us toward *Simulation Theory over *Theory-Theory *Theory of Mind (*ToM) construction, noted below, and which is contrary to the course goals. (*Simulation Theory and *Theory-Theory will be discussed later. Very briefly put, when we are imagining the thoughts, feelings, or actions of another we can use our broad knowledge of psychology and culture to make our conclusions—*Theory-Theory (A *ToM model based on theoretical speculation) or we can imagine what we would think, feel, or do in that situation—*Simulation Theory (we simulate the situation internally, with us at the center of the situation).

Second, we have a drive towards simplicity in interpretation, allowing considerable free play to cognitive habits that askew nuance or differences.[2] We can offer a number of evidence-based explanations of this tendency—discomfort with unfinished interpretations, the utilitarian efficacy of Bayesian inference for quick perception, or the power of the matched patterns themselves—but in any event we all have experienced times when our perceptions or understandings were off-target because of details missed or lost over time, to be replaced by a restructured, more patterned, simpler understanding. I would like to mention, in a speculative vein, one further possible reason: cognitive laziness. My sense is that, as we further probe the nature of cognitive processes we will discover that energy conservation is a component of many choices, including when we need interpretive results. A recent study, for example, has identified a resistance to intellectual effort as a factor in whether or not someone will feel empathy.[3]

The third “elephant” is *Simulation Theory (discussed later)—by far the usual way we model the mind of another, based on a principle of “What I would do in that situation.” We will discuss this in detail later but, as one can imagine, if oneself is the model for interpreting the thoughts, feelings, and actions (*TF/A) of another, if that individual is not of one’s cultural group, this approach can be a short path to misinterpretation. A large part of what we do in this class is to make us more aware of when and how we use this approach and when it might be better to replace it with something else.

Finally, my view of the “self” is that it is a collection of willed, semi-autonomous, and entirely autonomous cognitive processes, some of which we are fully conscious of, but with many operating subliminally or unconsciously. All of us have prejudices and all of us have only limited knowledge of the individuals whose thoughts, feelings, and actions we are interpreting, and most of us, I think, would agree that this is so. Nevertheless, when it comes to actual interpretations, we often downplay this reality and have a certain level of subjective certainty that our conclusions might not be perfect but are more or less “good enough.” The argument I am offering is that 1) often the interpretation falls short of the “good enough” standard—we are simply unaware that that is the case—and that, 2) with training, we can do better. We can become more aware of our semi-autonomous and autonomous cognitive processes. We can also, to some degree, reshape those processes through training and practice.

These elephants—cognitive self-centeredness, reluctance towards complex interpretive work, and situations where “we don’t know that we don’t know” (and think that we do) or do not know that much of how we decide the meaning of something operates in subliminal, pre-conscious or beyond-consciousness territory—are part of all the following comments on *patterns and, for that matter, are part of most of the assumptions that form the basis of this book.

8.2. “Early decisions”—subliminal priming, biases

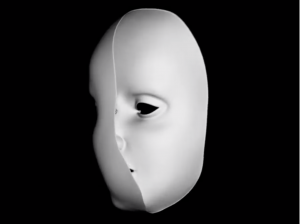

By “early decision” I mean when perception or interpretation is predisposed towards a certain direction even before an encounter with the data or code. For example, the famous “hollow-face illusion” refers to a perception error where my eyes tell me I am looking at a face with a normal convex, 3-dimensional (protruding) interpretive conclusion that it is indeed a face but, as the image rotates, I realize that I am instead looking at a concave (receding, “hollow”) modeling of a face that my brain has interpreted, in its stubbornness, as a convex object. The below is a screenshot from one example of this illusion[4]

Even after I realize the actual nature of the object, my “eyes” continue to insist it is a face, not a hollow mask. My logic tells me one thing, my eyes another, and I am surprised at how insistent my eyes are in suggesting it is a face with normal convex contour even when I try to “tell” my eyes to see it for what it is—”conceptual [our conscious interpretive cognitive steps—”logic”] and perceptual [our “eyes”] knowledge are largely separate.”[5]Our brains are hardwired to view faces as convex and will convert, unconsciously, information that contradicts that expectation. This is a simple example of what I am calling, playfully, an “early decision”—I have decided the interpretive outcome even before the facts are in.

Another example of “early decision [influence]” is subliminal priming.[6]Various experiments have explored the degree to which a stimulus so brief (for example, less than 500 milliseconds) so as to not reach as far as consciousness can influence interpretive outcomes. For example, in terms of influencing object *selection, police officers were subliminally primed with words like “threat” and “anger” in one case and “happy” in the case of another, then shown two neutral-expression faces side-by-side, one of an Afro-American man and one of a Caucasian man. Using eye-movement tracking to measure attention, the police officers spent, on the whole, more time looking at the black man’s face in the first scenario and more time looking at the white man’s face in the second.

Subliminal priming is widely used in advertising in an attempt to pre-decide our emotional reaction to products. What is relevant to us here is whether cultural content can be subliminal—and it would seem reasonable to think that is possible—and then whether its subliminal presence is sufficiently relevant in a *SO/M process when interpreting narratives so as to warrant our attention. I can imagine a few ways where this would be the case, but I feel this leads into highly speculative territory, and would, at this stage in the research, just like to present this as something to consider.

Expanding from the idea of subliminal stimulus that might bend interpretive conclusions, we can consider the effect of elements so pervasive and persistent that we are no longer aware of their participation in the interpretive process: implicit bias. In this book, implicit bias derives from the worldviews, ethical values, and common practices of a cultural group but of which the group lack self-critical awareness. [7]Cognitive bias is a broader category of interpretive inclinations and refers to tendencies in the cognitive processes that attribute meaning to incoming data.[8] Many of these involve simplifying that information and of course that includes an unnuanced used of patterns which, as I believe you can expect me to say, allows for cultural bias to overshadow the actual details of the data.

This, to me, fits in with many other areas of research indicating that cognitive processes seek high-value, low-energy expense solutions as the default mode. Thus, we will use predetermined outcomes (*patterns and *models) or the interpretive conclusions (opinions) of others first and only generate greater details when necessary. We will instinctively interpret along known lines rather than embrace the discomfort and energy required for new thinking. Learning is that effort to develop new thought but in most situations what we already know works well enough. On a day-to-day basis our approach is practical, not scholarly.

When teaching the Japanese aesthetic term “sabi,” for example, the challenge is to push students to think beyond the truly inadequate English translation of the term (“rustic beauty”) or (misleading Chinese character—寂—for those students whose first language is Chinese), and ask them to engage more nuanced and challenging definitions such as the famous, “Sabi is the color of haiku. This is not the same as haiku of tranquility.”[9]Even when we have discussed in some detail the important element of time implied by the term (sabu means “to rust”) and the aura of elegance that hovers around the concept, by the time a few weeks have passed, students have drifted back to the simpler formula “sabi = the lonely and sad, yet beautiful” which is almost, but not quite, true and misses the point of having the term at all.

In this way, newly learned content tends to devolve into simpler, more familiar concepts. This phenomenon is very important to our concerns about understanding narratives embedded in cultures other than our own: even when we expend the effort to understand unfamiliar interpretations, the achievement is not stable; rather, it is likely to devolve to a concept better known to “us,” or one whose nuances and details have been lost.

8.3. “Settled law”—the heavy influence of past interpretations

Settled law” is, again, a playful way to refer to another factor that can have enormous impact on an interpretive outcome. “Settle law” is similar to “early decisions” in that the interpretive disposition exists before the data or code is encountered. “Settled law” means, essentially, that a similar situation has been encountered in one’s personal past, an interpretation was made at that time, and for this new occasion the past interpretation is simply reused, slightly modified or not at all modified. “Settled law” in legal parlance means that a case has been debated at length and with care (perhaps even multiple times), a legal position (opinion) has been reached, that judgment (legal opinion) becomes precedent, and the precedent will not be overturned without good reason. This is a metaphor for the tendency to “jump to conclusions” based on previous experiences and have, sometimes, insufficient interest in adjusting one’s interpretation precisely to the data at hand.

8.4. Interpretive decisions made for one by others: cultural membership, mimetic desire

We understand that membership in a group is defined in part by our willingness to confirm the *WV/CP of the group. To what degree we will accept these worldviews and values is a shifting, complex phenomenon but we sense some boundary beyond which it is likely not safe to venture. To receive the security and benefits of group membership, a group member will tend to think what others think (normative and informational influence), to some degree at least. “Group-think” as suggested in the famous “Solomon Asch Conformity Experiment” is a symptom of delegating judgment and interpretive conclusion power to others.

“*Mimetic desire” was offered by the philosopher Rene Girard as the root of all desire; that is, we desire what we think others desire not simply what we personally think we want. His position is a careful one, supported by extensive philosophical consideration, and is grounded in the ethos of his day in Western Europe where identity is seen as arising from one’s social networks. This was of thinking can be found everyone in the theory offered in this volume.

8.5. Attractors

The concept of “*attractor” is a mathematical concept but it has found use in other fields, including cognitive psychology. As Wikipediadefines it: “In the mathematical field of dynamical systems, an attractor is a set of numerical values toward which a system tends to evolve, for a wide variety of starting conditions of the system. System values that get close enough to the attractor values remain close even if slightly disturbed.”[10] Or, as put succinctly elsewhere: “The most important thing to understand about attractors is that they are islands of stability in a sea of chaos. … Dynamic complex systems are inherently chaotic and unstable, but, they usually settle down into one of a number of possible steady states. These steady states are called “attractor basins . . .”[11]

*Cognitive attractors are networks of neurons that communicate with one another when information that is similar to the network is being processed. This will be represented to our consciousness as familiarity with the incoming information. Such *attractors, as neurological processes, participate in the SO/M interpretive process outside the boundaries of consciousness.[12]

8.6. Cultural attractors

While most *attractors interpret for us simple things that we should be very grateful are being interpreted rapidly and unconsciously by our mind, such as stop signs, the microbiologist/software engineer/philosopher Graziosi applies convincingly the concept onto the problem of the persistence of preconceived notions that block our accurate understanding of something. He offers a sustained consideration of how such *cultural or *cognitive attractors form and congeal into prejudices that can be exceptionally difficult to neutralize. As Graziosi observes, “the influence of reality is [unfortunately] indirect” and “the effort required to break the model attractor is guaranteed to be bigger than what’s required to affect the model contents, and because of this hierarchy, challenging a fundamental view (such as the validity of one religion or the other) is extremely difficult… .”[13] (Graziosi’s “model attractor” would be, in my terminology simply “attractor” since I would like to maintain the distinction between “patterns” (his “model”) which provide interpretive options during a matching process of incoming data to cognitive patterns constructed or already present and attractors, which have greater power of pulling partial information into them. Graziosi’s “fundament view” would be my “worldview” or “core value”—aspects of our affective-cognitive self that we are unconscious of but have fundamental shaping power for our interpretations, or such aspect that we are aware of but embrace unquestioningly, or aspects we are exceptionally unwilling to alter.)

It may be that one reason for the resistance I have encountered over the years in the classroom when asking students to “think like a premodern Japanese” (for example) was a key element in the advent of this book. The reluctance seems to go beyond a simple lack of knowledge of or interest in premodern Japanese culture. My observation is that some students could not be motivated sufficiently to do the heavy-lifting of looking past their own known patterns to construct new ones for reasons beyond just the difficulty or apparent irrelevance of the task. As I think will become evident, I am offering an interpretive theory that posits that to “think like a premodern Japanese” is subversive to one’s very sense of identity and that protective resistance is a natural reaction to the request. In other words, when we are confronted with something that seems to be familiar, attractors can cause us to conclude that it is in fact the familiar object we are associating with it.

This comes up often in my premodern literature classes where the complex emotion called by the Japanese aware, often translated as “pathos,” becomes just the usual vanilla-flavored emotion “sadness” or when a complex manifestation of a honne-tatemae expression, makoto, usually translated as sincerity, becomes, in the mind of some students, “saying what I want” as it is swept up in liberating, individualistic notions of self-determination rather than premodern Japanese notions of deference to social demands. The difference here is “being true to oneself” versus “being true to social expectations and norms”—a dramatic difference that matters when interpreting. However, the familiar-sounding word “sincerity,” split away as it becomes from the foreign word “makoto,” located the concept too close to Western notions of sincerity which revolve around being honest to something with that something, in the minds of some of my students, being oneself first and foremost. “Makoto” is pulled into the orbit of the cultural attractor “one should care for oneself” (itself a post-romantic derivative, perhaps, of Socrates “know thyself”) or “society can limit one’s freedom of expression and it is necessary to push back with courage” or such.

And, in a sense, this is “culture.” Instead of a cascade of random events in a region (linguistic or geographic), events repeat with great similarity because, as Sperber argues, “*cultural attractors” insure the fidelity of the repetition of the event. “Cultures do contain items— ideas, norms, tales, recipes, dances, rituals, tools, practices, and so on—that are produced again and again. These items remain self-similar over social space and time: in spite of variations, an Irish stew is an Irish stew, Little Red Riding Hood is Little Red Riding Hood and a samba is a samba.”[14]

Of course, for us involved in this course, the problem is that we end up perceiving as familiar something that really is, importantly, unfamiliar—we see it from within our culture, with our *cultural attractors nativizing it, rather than from within the culture to which it is “home.”

- Shouhang Yin et al., “Automatic Prioritization of Self-Referential Stimuli in Working Memory,” Psychological Science 30, no. 3 (March 1, 2019): 415–23, https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618818483. ↵

- "…the mind seeks the simplest available interpretation of observations— or, more precisely, that it balances a bias towards simplicity with a somewhat opposed constraint to choose models consistent with perceptual or cognitive observations." From the abstract to Jacob Feldman, “The Simplicity Principle in Perception and Cognition,” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews. Cognitive Science 7, no. 5 (September 2016): 330–40, https://doi.org/10.1002/wcs.1406. ↵

- C. Daryl Cameron et al., “Empathy Is Hard Work: People Choose to Avoid Empathy Because of Its Cognitive Costs,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, April 18, 2019, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/xge0000595. ↵

- Screenshot from "The Rotating Mask Illusion"at: eChalk, "The Rotating Mask Illusion," accessed April 27, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sKa0eaKsdA0&list=FLECaZdrUhWI0VfE_pY6BHaA&index=19&t=0s. ↵

- Richard L Gregory, “Knowledge in Perception and Illusion,” Professor Richard Gregory on-line, 1997, http://www.richardgregory.org/papers/knowl_illusion/knowledge-in-perception.htm. There are many examples online of this animated illusion. One I accessed while writing of this paragraph is at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sKa0eaKsdA0&list=FLECaZdrUhWI0VfE_pY6BHaA&index=19&t=0s. ↵

- For a review of the current state of the research, see Mohamed Elgendi, et al, “Subliminal Priming-State of the Art and Future Perspectives” Behavioral Sciences (Basel, Switzerland) 8, no. 6 (May 30, 2018), https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8060054. ↵

- See: “Understanding Implicit Bias,” accessed April 23, 2019, http://kirwaninstitute.osu.edu/research/understanding-implicit-bias/. The definition of implicit bias given there is: "Also known as implicit social cognition, implicit bias refers to the attitudes or stereotypes that affect our understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner." ↵

- For a list of 25 cognitive biases see, for example, “25 Cognitive Biases Home Page,” 25 Cognitive Biases - “The Psychology of Human Misjudgment,” accessed June 9, 2019, http://25cognitivebiases.com/. ↵

- Kyorai's Notes[Kyorai sho], ca. 1702-04. ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "Attractor," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, accessed January 8, 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attractor. ↵

- “Attractors in Complex Systems,” accessed May 31, 2019, http://www.stigmergicsystems.com/stig_v1/stigrefs/article6.html. ↵

- “How can the events in space and time which take place within the spatial boundary of a living organism be accounted for by physics and chemistry?” Karl Friston, Biswa Sengupta, and Gennaro Auletta, "Cognitive Dynamics: From Attractors to Active Inference," Proceedings of the IEEE 102, no. 4 (April 2014): 427-445, http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/6767058/. ↵

- Sergio Graziosi, "Cognitive Attractors," Writing My Own User Manual (blog), August 3, 2013, https://sergiograziosi.wordpress.com/2013/08/03/cognitive-attractors./ ↵

- Dan Sperber, "Cultural Attractors," Edge—2011: What scientific concept would improve everybody's cognitive toolkit? (response), accessed January 8, 2018, https://www.edge.org/response-detail/10950. ↵