"High order / low order" love ◆ Neurochemical, affective, and cognitive love

Key terms and concepts introduced in this chapter:

- love

- neurochemical love

- affective love

- cognitive love

Key terms and concepts mentioned in this chapter that should now be familiar:

- emergence

12.1. The problem of “Same yet different”

Early in my teaching career, as I developed some skill in reading 10th-century Japanese narratives and wished to convey as accurately as possible how I thought they should be understood, I noticed that my reading of those texts had evolved by stumbling through a series of misreadings, and that more often than not this was due to a misapplication of context.

A simple example of this would be my interpretive assumption that:

Heian women are unhappy because they do not have equality in their marriages.

A more informed reading position for Heian period narratives written by women, I came to understands was:

High- and mid-level aristocratic Heian women become anxious when their social rank or standing seems at risk, given the public shame that might ensue but, more importantly, what this might mean for the future promotions (career) of their children.

The first assumption was an extension of what I had originally felt was a universal principle, one that could be applied across cultures and times:

When people lack equality, they are dissatisfied.

As time went on, I discovered how unaware I was that I had affiliated myself with what is basically an American political creed affirming the often-quoted passage in the Constitution:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, …”

although I would suggest that it is culturally present now mainly as the *derivative:

Everyone should be treated with equality and fairness.

As the culture of Heian Japan—as best as I could recreate it with fidelity—became more “second nature” to me, I could apply, and with better nuance, more appropriate contexts of the narrative. That women were discontent was accurate, but the reasons for their discontent were entirely different and had nothing to do with equality or even want of respectful treatment by their spouses.

As I tried to convey to my students the importance of constructing and skillfully using appropriate contexts to better read a situation or text, it seemed to me that many of them believed with considerable comfort and certainty that the experience of *love is universal, being the same in its important points across cultures and times just as they had been (erroneously, I would argue) taught that “music is a universal language.”

In other words, they were not too concerned about contexts and the game-changing power of them.

Yet my career in interpreting texts that are embedded in a plethora of difficult cultures has shown to me time and again that despite my best intentions of reading with care, misunderstandings are a constant for my own readings and those of my students. Although in this course our objects of analysis are *narratives, it might also be worth noting that this difficulty is most definitely not limited to the act of trying to understand the *code that will become a text. It is, I suggest, endemic to one’s daily life—especially if one works in a culturally diverse situation. Whether we are discussing narratives or “real life,” some of these misunderstandings are minor but some result from profoundly different views of *love—so different, in fact, that one of the individuals in the relationship could never guess, or perhaps even understand, what the other individual is thinking.

So, how do we explain the apparent contradictions suggested by, on the one hand, a “gut-level” sensation that we all know what *love is and that in essence it need not be defined and that love stories can be more or less understood and enjoyed across cultures, while, on the other, discovering and overcoming misinterpretations?

My thinking on this conundrum led to the broader question of the nexus between body and culture.

12.2. Our method puts high-order cognitive love first

Research suggests (though not without controversy) that there are basic, primitive emotions in humans that are recognizable across cultures, emotions that produce universal facial expressions that members of significantly different cultures can recognize.[1] Research into microexpressions (fleeting expressions on the human face that communicate emotional states unrelated to the will of the individual with the expression) is grounded in this premise.[2] It is possible that dopamine is involved in the interpersonal harmonization of limbic systems of face-to-face communication, especially when looking into another’s eyes.[3] Similarly, contagious scratching produces the appearance and sensation of interpersonal harmony or empathy arising from free will (cognition) but which may be only chemical or hardwired and neurological in basis.[4]

Vertebrates share a similar primal brain structure and mammals share a complex emotional life supported by the limbic system; but, complex cognitive perception of all these more basic feelings is generated by the cerebral cortex that is by far most highly developed in humans.[5] Some brain structures, including structures that generate sensations of love, are not shared just among humans but all mammals (and in some details beyond mammals to other vertebrae) and feelings of love that would be familiar to us may be more widely distributed among mammals that we generally assume. For example, while most of us would probably be ready to grant to other primates the ability to love, it is also scientifically within the range of the credible to say that your dog really does love you rather than just appears to love you (if we take love to mean an emotionally meaningful connection or bond). It has been shown that dogs generate and respond to levels of the neurohormone / neurotransmitter oxytocin—identified as key to sensations and behaviors of bonding—in ways different from wolves.[6] Dogs might also engage in contagious yawning, another indicator of empathy.[7]

The nexus between the incredible experience of feeling love for another (or for anyone or everyone for that matter) and the body and mind that are home to that event is just exceptionally interesting. Research in this area is developing so rapidly that my comments here can be called the results of recent research but certainly not the newest research. For example, we have known for some time that oxytocin is important to sensations of intimacy and bonding, but, puzzlingly, it seem also to be produced in times of separation.[8]

I hope you can see how quickly the topic of “the affective neuroscience of love”[9] branches into many directions. Such research as the above strongly indicates that there is an essential, important, and powerful aspect to the experience of *love that is indeed universal and recognizable across cultural boundaries, even easily.

While I want to acknowledge this and fully support that if we are to truly talk about *love in a significant way these aspects must be included. However, for the purposes of this course we must make this choice in our focus:

If we are to understand cultural differences in how love is narrated and perhaps even experienced, we should NOT focus on the biology of love.

Therefore, for the purposes of this course and the project it takes on, we avoid analyzing *love in its powerful physical manifestations of desire and bonding, and the primal emotions that can go with the experience, such as joy and fear. If we analyze these, we go opposite the direction that the class should proceed—we end up collapsing and erasing cultural and individual differences in articulating, understanding, and experiencing love to arrive at the simple “everyone feels love.”

That does not help us much. Therefore, we lean away from the corporal experience with its hormones and affect to focus almost exclusively on the high-order cognitive representations of love. Our course standard is “*always about high-order love.” In our exploration of *worldviews, *ethical values, and *common practices (*WV/CP), using love narratives as the place in which we do this, we want to have in the background as a guide for our analysis attentive concern to this question, even if it goes, ultimately, unanswered: “How do cultures encode, articulate, understand, and experience love through the signs and various meanings that are dynamically alive within that culture, embedded within that culture?” When stated as a standard, this is called “embracing cognitive love.” It is true—such questions do not capture the power of the love experience, or the joy of reading love stories, but they do allow us to consider cultural differences and how cultural differences lead to different ways of interpreting, understanding and experiencing what we so easily and naturally call “love.” We do not have to solve the thorny question of how, in fact, does something corporal, such as affective experiences of love, interact with something that is a social construct: culture? Nevertheless, we must be aware of it.

12.3. Focusing our analysis — A love lexicon for this course

Bonding with another engages the mind and body in broad and complex ways. The affective components of love such as desire, longing, disorientation and distraction, urge to nurture, urge to make gift, sense of security, urge to protect, pleasure of giving and receiving attention, feelings of intimacy all manifest to us as somehow true, deep, and real and, further (or because of that), have a presence in culture associated with authenticity. It is, therefore, normal when we talk about *love to gravitate towards these highly accessible, culturally affirmed components. Descriptions of “real” or “true” love insists, I would suggest, on an affect component—not necessarily in the world of theory but in the practical, “on the street” way of considering these things. Love without the warmth or turbulence of affective states seems to be missing something.

If our goal, then, was a full or authentic study of the texts we read and the films we view, I would suggest than an affect-centric approach may well indeed be one of the best critical approaches. However, that is not what we do in this course. Instead, we are asking how culture—at multiple levels, some of which we are aware and others which go unnoticed—shapes our experience of love. And to that end I have created the following lexicon to help us sort out the directions of our investigations into love narrative and have a shared set of terms for doing so. These terms describe physical and mental states that *mix into one another, produce and alter one another, and, taken as an interactive set with tensions and harmonies both, can represent much of what we call love for the terms of this course.

*Neurochemical love. These are neurohormonal cascades and systemic responses that alter the state of our body toward or away from bonding, harmonizing with another, intimacy, sexual arousal, and so on. These neurochemical activities help preserve memories by associating them with specific emotions (and physical location, too, but this is beyond the scope of our course). They originate in non-discursive areas of the brain, especially the limbic system (and in particular the amygdala, hypothalamus, and hippocampus), but seem also to be dynamically linked to the makeup of the bacterial flora in the gastrointestinal tract. They are outside of the reach of our consciousness, manifesting instead as bodily sensations, bodily changes, and supporting, causing, or influencing affects (emotions).

*Affective love. These are emotions and emotional sensations related to love. We will use the term broadly. Examples would be swooning, yearning, familiarity, jealousy, impulses to nurture or protect or possess or dominate, impulses or sensations of receiving nurture, or being protected, or being possessed, or submitting, urges toward gift-giving,[10] desire for attention, sexual attraction, “nesting” instinct, and so on. Affects are an extremely important context for cognition (interpretation, decision-making, and so on). When discussing these in our analysis, we refer to them as “feelings” or “states-of-mind.”

*Cognitive love. These are our conscious thoughts about love such as future-looking strategic thinking (such as “Should I accept the job offer or move to Bali with this guy?”) and mental processes of decision-making (such as “Should I admit I have slept with someone else?”), and present-time ruminations such as the interpretation of situations and individuals (such as “I think he likes me as much as I like him”). These cognitive processes turn on expectations (such as “She will call again today”) and aspirations (such as “I hope this lasts forever”) that draw heavily on memory. These are also the narratives (stories) we tell ourselves about love: “I am in love.” “My partner will leave me just as my previous partner did.” “We are star-crossed lovers.” “It was during that fantastic in Hawaii that we became close.” Cognitive love sweeps up into it other desires that might, of themselves, not seem like love but are a very important part of partnering. Examples would be the desire for *status that might be derived from a relationship, seeking consolation from loneliness or grief, the pleasure of sharing, and so on. Cognitive love is so involved in affective states (generating them and being generated by them) that it might be more accurate simply to talk about “affective cognition”. However, this would take our focus off the role that the external features of *worldviews, *ethical values, and *common practices play in shaping our aspirations, expectations, actions (and reactions) and general interpretation of situations and people (construction of *ToM).

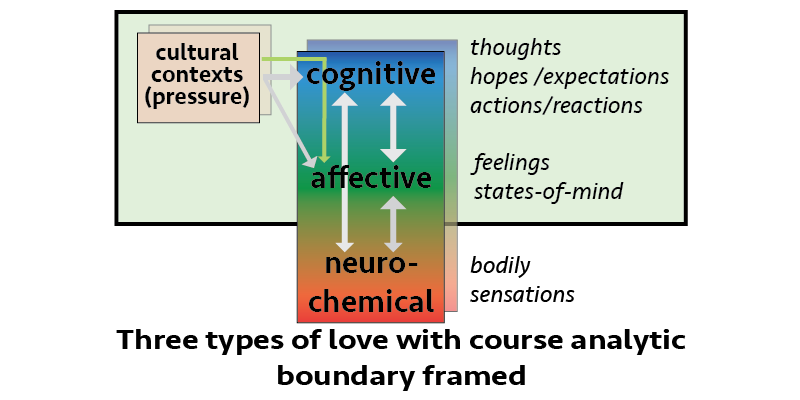

The below chart relates the above three categories of love in a *”high order” / “low order” schema, with neurochemistry applying pressure from below,[11] but with the higher emotional and cognitive states producing their own pressure back down through the system. It indicates how an individual (and a cognizing, conscious entity) receives influence from the body, the emotions and cultural contexts. The cultural contexts box, as well as the love aspects box are shadowed with a second box behind, indicating that there are multiple contexts and multiple states of the individual. These may be contradictory or work more in tandem. The green arrow passing through “cognitive” and then heading down to “affective” is, in my opinion, the more likely pathway that culture affects emotions but there is no need to decide this for the purposes of the course. Finally, the green framed box indicates the range of our analytic exploration, but, it should be noted, with an emphasis towards cognition.

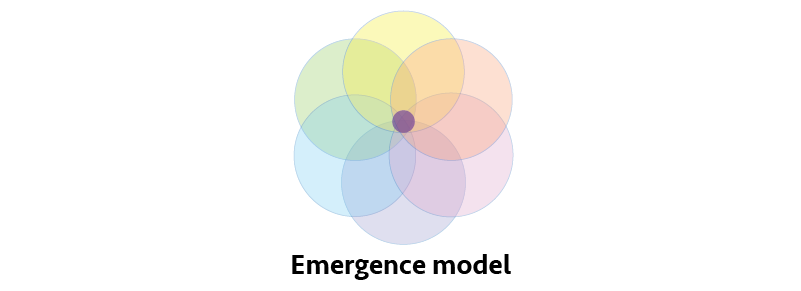

*Emergent love. I would like to add one more term to our lexicon: emergent love. *Emergence is an important concept for this course. It is part of the *CDE reports, names the primary benefit of our many class discussions, and, in this case, attempts to give a “location” for love within a narrative. Each of the below spheres can indicate something related to love—they need not be of the same type or intensity. So, for example, one sphere could be “this new partner looks just like my previous one:” and another could be “our country is at war, and I am so afraid and in need of support:” and another “whenever she looks into my eyes my whole body shakes;” and another “we have broken up and gotten back together three times now …. .” The point is that collectively these all work upon each other and that the dynamic generates something that is not any one of them and that is not just a sum of all of them either, but it, instead, is its own “entity” or, rather, “something.” That “something,” I would like to suggest, is the best definition of love in a sentence like “I am in love” or “I have loved deeply once in my life.” We tend to measure love in terms of its affective intensity (“I can only think of my lover these days”), or trust/reliability (“He has been true to me all these years”), or its parental-like aspect (unselfish, giving love). This, often, is our measure of a “good” love or a “true” love. But I would like to suggest a broader understanding of it, one that includes many aspects of our life all colliding with one another. Then there, at the center, is the emergence of something that is more than any one of the circles. While these are my thoughts, we do not explicitly analyze this sort of emergent love in this course. I am outlining it now because it often seems like we are not talking about the heart of the matter of a narrative when discussing just one of the spheres, such as whether a person’s actions are trustworthy in terms of a traditional Confucian understanding of that term. We work with highly defined bits-and-pieces of the total experience of love, to explore cultural *worldviews, *values, and *common practices. In the below graphic, the dark spot at the center symbolizes “emergent love”.

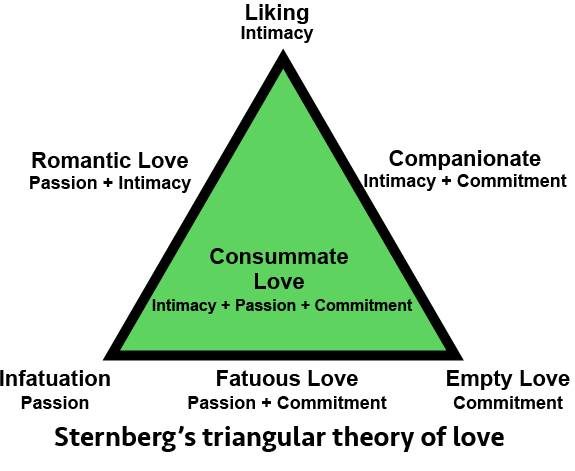

I would like to share here one other schema. It can be useful as a way of thinking about love, but I would also like to measure it against the schema just offered, as a way of better understanding *emergence.

This other schema is usually called “Sternberg’s triangle” or “Sternberg’s triangular theory of love,” after the Cornell professor of Human Development, and is part of a larger theory of love that he offers.[12] His theory distributes three primary modes of loving—intimacy, passion, and commitment—to the three apexes of a triangle, then categorizes love by combinations. In the previous chart’s way of distinguishing aspects of love, Sternberg’s “commitment” would be primarily cognitive and based on an affirmation of *ethical values, while his “intimacy” would be primarily affective and neurochemical, and his “passion” would be primarily neurochemical. His consummate love would be the organic whole of when all of these are fully present or an emergent effect of them, it is not clear. The schema has the power of simplicity but seems primarily meant to explain “bonding” of different types rather than the full range of experiences that seem relevant to love (when offering a model that has broad descriptive intent).

- Paul Ekman, Emotions Revealed: Recognizing Faces and Feelings to Improve Communication and Emotional Life (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2003), https://zscalarts.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/emotions-revealed-by-paul-ekman1.pdf. Ekman asserts that there are six such primal emotions: "happy," "surprise," "fear," "disgust," "anger," and "sad." Ekman showed photographs of human facial expressions to members of various cultural groups around the world to determine whether an emotion could be identified without explanation. The results showed that expressions associated with these emotions were, more or less, universally recognized. Panksepp would add to Ekman's list a seventh: "agony." See, Jaak Panksepp, Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), ProQuest Ebook Central. He also would like to point our attention to seven "Primary-process affective systems," namely, "seeking," "anger," "fear," "panic-grief," "maternal care," "pleasure/lust," and "play." Meanwhile, Jack recently argues for just four, ignoring "agony" and collapsing four on Ekman's list into two: "surprise-fear" and "disgust-anger". See, Rachel E. Jack, Oliver G.B. Garrod, and Philippe G. Schyns, "Dynamic Facial Expressions of Emotion Transmit an Evolving Hierarchy of Signals over Time," Current Biology 24, no. 2 (January 2014): 187–192, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2013.11.064. ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "Microexpression," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, accessed Oct 6, 2017, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Microexpression. ↵

- Wikipedia contributors, "Limbic Resonance," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, accessed Oct 6, 2017, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Limbic_resonance. ↵

- This contagious itch behavior is actually coded into your brain," he [Zhou-feng Chen] says. "Contagious itch is innate and hardwired instinctual behavior." Ben Panko, "Why Is Itching So Contagious?" Smithsonian.com, March 10, 2017, http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/why-itching-so-contagious-180962484/#kXmTilqdMQIYivli.99 ↵

- For basic information on brain anatomy, see, "The Human Brain," Annenberg Learner—Discovering Psychology, accessed December 27, 2017, http://www.learner.org/series/discoveringpsychology/brain/brain_nonflash.html. ↵

- See, Miho Nagasawa, et al., "Oxytocin-gaze positive loop and the coevolution of human-dog bonds,” Science 348, no. 6232 (April 17, 2015): 333-336, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1261022. See also, Mia E. Persson, et al., "Intranasal oxytocin and a polymorphism in the oxytocin receptor gene are associated with human-directed social behavior in golden retriever dogs," Hormones and Behavior 95 (Sept 2017): 85-93, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2017.07.016. ↵

- Jason G. Goldman, "Contagious Yawning: Evidence of Empathy?" Scientific American (May 17, 2012), https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/thoughtful-animal/contagious-yawning-evidence-of-empathy/. ↵

- Tori DeAngelis, "The two faces of oxytocin—Why does the 'tend and befriend' hormone come into play at the best and worst of times?" American Psychological Association 11, no. 2 (February 2008), http://www.apa.org/monitor/feb08/oxytocin.aspx. ↵

- The phrase is borrowed from Jaak Panksepp, Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), ProQuest Ebook Central. ↵

- Male Eurasian jays, for example, are known to give gifts to female jays that they have estimated would be the preferred gift. See, Brandon Keim, "Gift-Giving Birds May Think Much Like People," Wired (Feb 4, 2013), https://www.wired.com/2013/02/jay-theory-of-mind/. ↵

- Jaak Panksepp, "Primal emotions and cultural evolution of language: Primal affects empower words," in Emotion in Language: Theory – research – application, ed. Ulrike M. Lüdtke [Consciousness & Emotion Book Series 10] (John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2015), 27-48, http://www.jbe-platform.com/content/books/9789027267658. ↵

- Robert J. Sternberg, "Robert J. Sternberg," accessed December 27, 2017, http://www.robertjsternberg.com/love/. ↵