Karen Overhill ◆ pluralities ◆ interpretive balance

Key terms and concepts introduced in this chapter:

- pluralities

Key terms and concepts mentioned in this chapter that should now be familiar:

- attractors

- Connectionism

- cultural contexts

- emergence

- mixtures

- ToM

15.1. Karen Overhill’s crowd of seventeen

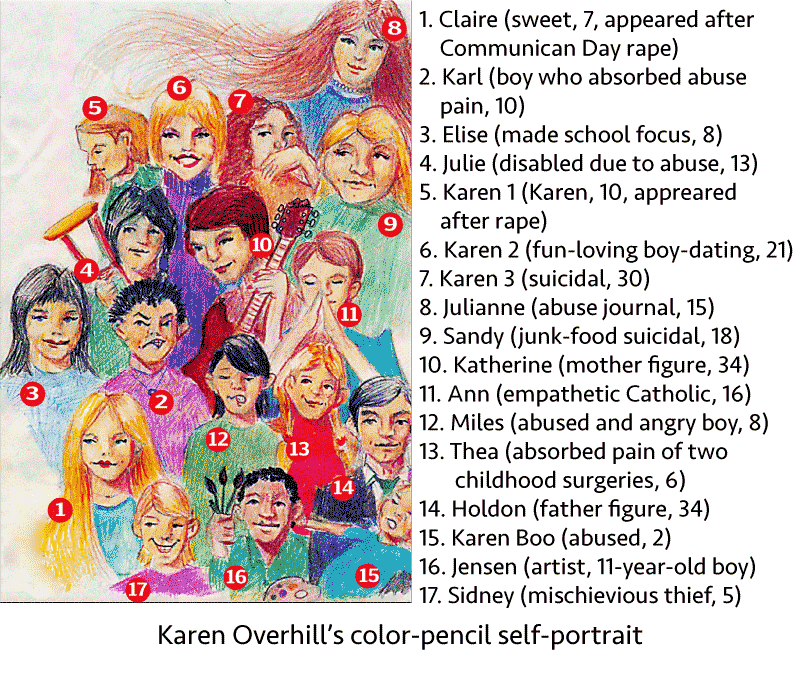

I would like now to take a moment to offer the case of Dissociative Identity Disorder (Multiple Personality Disorder)[1] of Karen Overhill and her seventeen personalities. After working with her therapist over an 18-year period beginning in 1989 to help “her”—the “Karen” meeting regularly with her therapist—become more directly aware of these multiple personalities, one of her personalities drew a portrait of all seventeen and placed it in an envelope for her to give to her therapist:

The next session Karen brings an envelope. I’m stunned. Inside is a drawing of seventeen faces. I’m amazed at the quality. I assume it is a picture of the parts inside Karen, but I’m not sure who is who. I can identify Holdon, and Jensen, because he is supposed to be black, and he is holding paintbrushes. I can only guess at the others. I show it to Karen. She shrugs her shoulders and turns red, but smiles a little.

“I don’t know what to say,” Karen says, holding the picture away from her with discomfort. “I guess I must have done it.” She hadn’t opened the envelope, and hasn’t seen the picture.[2]

15.2. Embracing pluralities

It is debated as to what degree and frequency Dissociative Identity Disorder is actually present in people,[3]. However, we do not need to concern ourselves with sorting out the various points of view. I offer Ms. Overhill’s case only as a startling illustration of an important set of principles for when we are considering the level of influence of specific *cultural contexts and motivations that we can attribute to *ToM, namely, *autonomous entities, *competitive multiplicities, *layering, and *alternating contexts. I would like to call these, collectively, *pluralities.

Like *mixtures, including *pluralities in our analysis helps us avoid the temptation to over-simply the highly complex nature of our relationship to *cultural contexts. The fundamental difference between them is simply that in the case of *mixtures, different aspects or factors have so blended that it is impossible to meaningfully analyze them as separate entities. For example, in some narrative cases “insecurity” and “jealousy” should be simply a blended unit as we put together a *ToM. Trying to decide which came first or which is the lead element is a hopeless venture. *Pluralities are also multicomponent entities but unlike *mixtures each remains, to some degree, distinct from the other. I will offer four types of *pluralities in a moment.

Although we are quite comfortable with fractured and shuffled experiences in many ways, our pattern-oriented, egocentric brain wants to be the boss of the shop. Karen’s case upends a natural, intuitive assumption that we have, namely, that there is just one “me” in life, in this body. Freud (though he was not alone in the research) successfully fractured the human into two: the conscious and unconscious, positing that there is part of “me” that I can never directly observe, communicate with, or control. But even in the face of this assertion, we continue to think of “me” as essentially one “me” even if I am sometimes “at odds” with myself. It is just our normal operative position: “I” do things, decide things, feel things. This is the intuitive feel of consciousness. It is supported by a wide range of religious perspectives: the atman of Hinduism, the psyche of the Greeks, and the soul (English term) of religions arising from the Mesopotamian region (the Abrahamic faiths of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam). Buddhism, which asserts that there is no self (an-atman / “no atman“) explains this (false) sense of continuity as karmic effect. (Daoism recognizes different entities but puts them in a dialogic relationship: one cannot exist without the other.)

If our arm moves “on its own,” this is troubling. If we have seventeen personalities within us, each not communicating well with the other, it is a mental illness. (As one newspaper article reports the “solution” to Overhill’s problem: “Baer and Karen agreed to heal her disorder by integrating the personalities.”[4] Emphasis mine.) Isn’t there a “me” in command of it all?

But it seems fairly evident that postmodernism, networked life, and even the expanding knowledge of physiology are taking us in a different direction, suggesting we are a conglomerate of systems that are highly interactive but often through competition among systems rather than harmonious coordination. This is my view of the human body, the human brain (and the *emergent “mind” of it), and cultures: they are fractured entities with a variety of autonomous systems (most unconscious to us as individuals, or, in the case of culture, unspoken and never critically examined behaviors, practices, and opinions) in messy interaction. *Emerging from this is a “me” or sorts. *Emerging from this are cultures in their reality: fluid, evolving loosely associated constellations of opinions and practices with no essential identity to be fully discovered or fully defined. Thus, if we want some comprehensive and open consideration of the complexity of culture, I believe we need to accept that it is not just one thing, it is many things all mashed together into a complicated experience of life. If we ask the question, “How much Buddhism is there now, really, among 20-year-olds living in Seoul Korea?” we do not need to worry as keenly about *pluralities (although I would venture that *mixtures remain a necessary consideration). But, that is not what we do. Instead we are contemplating the more complicated question: “For this person (*ToM, actually) in this situation, at this moment, what is the array of cultural contexts that bear down up and help information her thoughts, feelings, and actions? What matters and what doesn’t?” That question most certainly needs to embrace the notion of *pluralities, even if it makes our task considerably more difficult.

15.3. Pluralities and interpretive balance

How do we deal with *pluralities?

In the real world I think we just accept a certain level of confusion, indecision, inaccuracy in perception, and so on. Part of getting the business of life done is to not get stuck on each contradiction that comes along.

However, in the case of analytic projects, we are tempted to untangle, clarify, solve or dissolve contradictions that the multiplicity of cultural contexts bring to the situation. As our first movement in managing this, we work with *instances rather than extended portions of a narrative. We use the full narrative to help us understand the *instance, but we keep our analytic conclusions focused on the *instance. This helps considerably but the task remains daunting in its complexity and it can be hard to share analytic results with others.

I would like to suggest that the most authentic and useful analysis will strike a good balance between accepting the many bits and pieces of ourselves and our cultures just “as they are,” on the one hand, (this is, by the way, a Buddhist position) yet, on the other, find common, simple denominators when they are plausibly there (the Holy Grail, perhaps, of Western analysis). Simple descriptions sometimes appear to be the most forceful ones but in this we should be cautious. I believe It is unwise (leads to misperception) for us to push too energetically this process on finding the “essentials” of a cultural moment. Ultimately, we are dealing with messy topics. When it comes to living culture, and living in culture, Occam’s Razor (a very wonderful concept to be sure) is less helpful as an analytic tool than embracing the subversive positions towards predictability and repeatability that chaos theory, game theory, and such suggest.

One more point on this — besides asserting that we interact with *cultural contexts in a huge range of ways, I would like to add one more theoretical position that warns against finding singular answers to human behavior—Freud’s fondness in his Interpretation of Dreams regarding “overdetermination.” The assertion is that we cannot assume that a person’s particular behavior or reason for a particular dream can be traced back to a simple cause but rather that behavior (or an explanation for a dream) is “overdetermined” — there are more reasons than necessary to explain it. In short, Freud wants to sweep aside the idea that, when it comes to the human mind, the least complex explanation should be taken as the most likely explanation.

Where does that leave us?

As you can guess, I believe we need to have a certain level of tolerance towards the contradictions of our conclusions. We should not seek air-tight, fully defensible descriptions of cultural influences. (“He did that because he is a Buddhist at heart.”) But more importantly, I would like us to be careful not to over-use or over-extend an explanation: “Well, if X person thinks this, then X person will also not do that.” That can be easily inaccurate.

For example, imagine that you have noticed that Japanese usually take their shoes off before going into private living spaces and later you notice that they do this for many places where one would think it is nice to have clean floor. You deduce: “Japanese like cleanliness.” Then you visit a national park and see a Japanese throwing his food trash along the side of a trail. You sense a contradiction because you assume that national parks are in the category of “nice places” but now you wonder: What is the difference between homes and other nice places and national parks? Am I missing a category somehow?

But maybe that is not the best line of thought. Perhaps more accurately you should think simply, “Japanese like cleanliness except when they don’t” and leave it at that. Going back to our earlier argument as to whether culture is a collection of principles or just a million memorized behaviors (*Connectionism), this could be reframed as just this interpretation: “Japanese like cleanliness but this person saw someone else toss trash and so decided to do that same.” (We will later call this type of behavior and its influence on decision making *common practices.)

This is the tension in the effort to interpret (or at least in building a theory behind the effort): Is “I saw someone else do it, so I can do it” a principle or just learned behavior? To me, there is no definitive answer and so, in short, while we can and should attempt to sort out principles toward understanding, a good dose of caution should be including in the process. This is the main point of the reason I have introduced the idea of *pluralities: Without leaving the door open to contradictions when considering culture, that is, without embracing *pluralities and the incompleteness in analytic description and conclusion that they will ultimately demand, we will miss too much. The “blindness” discussed in the chapter on misunderstandings was said to be the result of “horizons of expectations” creating limits to imagination, on the one hand, and attractors or models offering to rapid and complete answers, on the other. Here I am arguing that in a desire for simplicity in argument or conclusion, or simply the desire to get to some sort of conclusion, we feel dismay at the added layer of complexity that *pluralities impose. A less conflicted way of saying this might be: Culture (life, for that matter) is the texture of *mixtures and *pluralities that are so complex as to escape full capture in any descriptive effort. Cultural can be lived but it cannot be spelled out in its every detail.

- "Formerly known as multiple personality disorder, this disorder is characterized by 'switching' to alternate identities. You may feel the presence of two or more people talking or living inside your head, and you may feel as though you're possessed by other identities. Each identity may have a unique name, personal history and characteristics, including obvious differences in voice, gender, mannerisms and even such physical qualities as the need for eyeglasses. There also are differences in how familiar each identity is with the others." "Dissociative Disorders," Mayo Clinic, accessed January 29, 2018, https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/dissociative-disorders/symptoms-causes/syc-20355215. ↵

- Richard Baer, Switching Time: A Doctor's Harrowing Story of Treating a Woman with 17 Personalities, "Chapter 13: Family Tree," New York: Three Rivers Press, 2007. Kindle Edition. ↵

- Paulette M. Gillig, "Dissociative Identity Disorder: A Controversial Diagnosis," Psychiatry (Edgmont) 6, no. 3 (March 2009): 24–29, accessed January 29, 2018, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2719457/ ↵

- Pam DeFiglio, "Doctor helps woman with 17 personalities on 'long path of healing'," Daily Herald, October 8, 2007, accessed January 29, 2018, http://prev.dailyherald.com/story/?id=53173 . ↵