7 Pectoral and Pelvic Girdles

Objectives

- Identify and orient the bony elements and associated structures of the pectoral and pelvic girdles of fish, amphibians, squamates, crocodilians, birds, and mammals.

- Correlate the major differences in limb girdle morphology with basic locomotor adaptations.

- Fathom the evolutionary changes associated with the transition from the basal synapsids (with a sprawling posture) to modern mammals (with stacked limbs).

Overview

The postcranium of the vertebrate skeleton is divided into axial and appendicular components. The axial skeleton includes the vertebrae, ribs, and sternum, which you became familiar with in the previous lab. In this lab you will explore the appendicular skeleton of vertebrates, which includes the girdles and the four limbs. Paired appendages are one of the features that distinguish vertebrates from their chordate ancestors. Throughout vertebrate evolution, a diversity of appendage morphologies has emerged, linked to a variety of locomotor modes and lifestyles. The girdles connect the axial and appendicular skeletons. In fishes, the pectoral girdle attaches to the skull, but the pelvic girdle is not attached to the axial skeleton. In tetrapods, the bones of the pectoral girdle lose contact with the skull and attach to the axial skeleton via muscles and ligaments. The pelvic girdle, however, articulates with at least one vertebra and provides rigid, non-muscular support, thereby reducing the energy required to elevate the body over the limbs. Most vertebrates retain a free-floating pectoral girdle, attached by muscles and ligaments to the axial skeleton.

See the terms list here: Terms 7.1

The Pectoral Girdle

Non-Tetrapods

On each side of the pectoral girdle of chondrichthyans (e.g., sharks) there is one large scapulocoracoid where the scapula and anterior coracoid form a unit. The ventral portion is called the coracoid bar, the dorsal part is called the suprascapula, and the spine that extends dorsally from the middle region is called the scapular process. The area where the fin articulates is called the glenoid region.

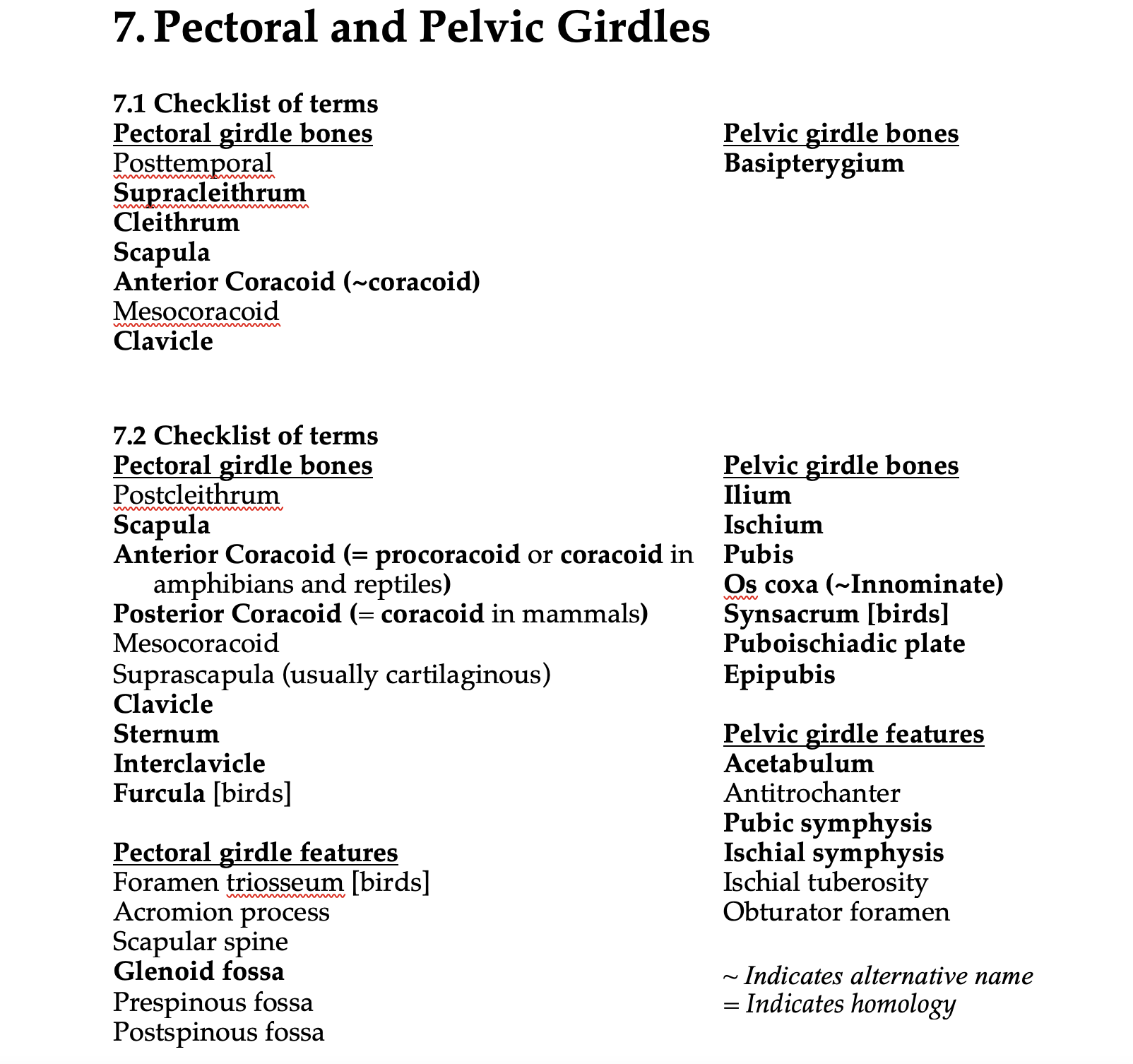

In bony fish, the pectoral girdle has both endochondral and intramembranous (dermal) components. The endochondral elements include the scapula and the anterior coracoid. The dermal bones include the cleithrum, which is always present, and a supracleithrum, posttemporal, and a clavicle, which are absent in some lineages.

Figure 7.1. Pectoral girdles of gar (Lepisosteus), bowfin (Amia), and salmon (Oncorhynchus), clockwise from the top. Illustrations from Jollie (1962) under CC0 public domain.

Tetrapods

In tetrapods, the pectoral girdle attaches to the vertebrae via a muscular sling. The two endochondral bones of the pectoral girdle are the coracoid (which is ventral and contacts the sternum) and the scapula (dorsal). Where the scapula and the coracoid meet, they form the glenoid fossa—the site of articulation for the forelimb. Note that the “coracoid” in fishes and the “coracoid” in mammals are not homologous. In fishes and early tetrapods, the “coracoid” refers to the anterior coracoid (or procoracoid). However, in synapsids a second “coracoid” evolved: the posterior coracoid. All therian mammals have lost the anterior coracoid but retain the posterior coracoid. The dermal bones are evolutionarily lost to varying degrees across tetrapods.

Amphibia

In early tetrapods and amphibians, the endochondral elements are the anterior coracoid, posterior coracoid, and scapula. The dermal elements that are present in the pectoral girdle are the cleithrum, clavicle, and interclavicle.

Amniota

Most amniotes possess a scapula and either an anterior coracoid (procoracoid), a posterior coracoid, or both, and this represents the endochondral component of the amniote pectoral girdle. The single “coracoid” in amphibians, birds, and reptiles is the anterior coracoid (procoracoid). The single “coracoid” element in therian mammals is the posterior coracoid (simply referred to as the coracoid in this context). Basal synapsids and monotremes generally have both anterior and posterior coracoids. A clavicle and interclavicle may be present as the intramembranous component of the girdle.

Testudines

Turtle pectoral girdles are inside of the rib cage rather than outside of it. This is unique in vertebrates. The acromion is unique to turtles. As in other sauropsids, the cleithrum is lost.

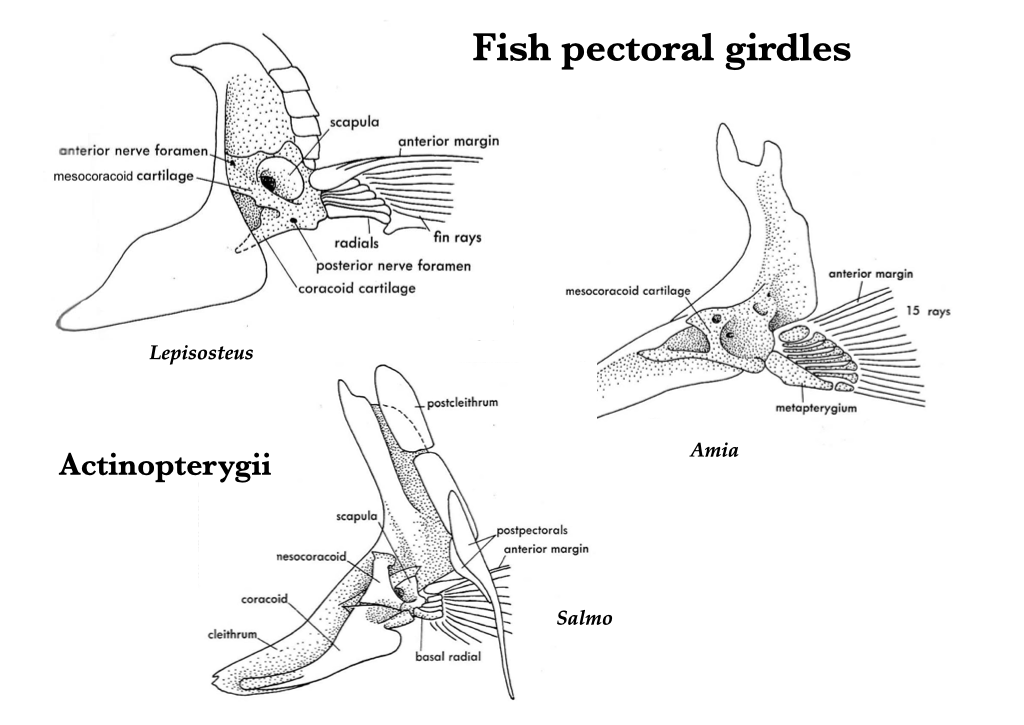

Squamates

Lizards, except for chameleons, have clavicles and an interclavicle, but the cleithrum is lost. Suprascapulae are often present in lizards, but they remain cartilaginous, and the pectoral girdle is firmly attached to the sternum. Snakes lack limb girdles.

Figure 7.2. Pectoral girdle of an iguana (Iguana) in ventral view. Illustration from Jollie (1962) under CC0 public domain.

Crocodylia

Crocodilians lack clavicles and cleithra, but they have a small interclavicle that is ventral and anterior to the sternum.

Aves

Birds have a specialized pectoral girdle, with a large anterior coracoid, a thin scapula, and the clavicles fuse with the interclavicle to form the furcula (wishbone).

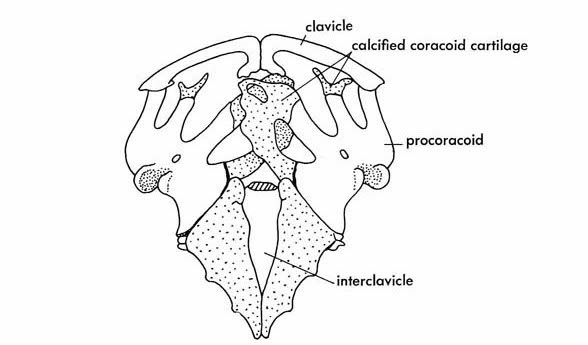

Mammalia

Mammalian pectoral girdles vary considerably in morphology. In monotremes, the scapula, posterior coracoid, anterior coracoid, clavicles, and interclavicle are all present. In therian mammals (marsupials + placentals), the endochondral component of the pectoral girdle has lost the anterior coracoid, and the posterior coracoid is reduced to a process on the scapula. The only intramembranous component is the clavicle, and the clavicle is the only bony connection of the pectoral girdle to the axial skeleton. Thus, only the scapula contributes to the glenoid fossa.

Figure 7.3. Mammalian pectoral girdles: armadillo (A), sloth (B), opossum (C). From Jollie (1962) under CC0 public domain.

The Pelvic Girdle

Non-Tetrapods

In sharks, the pelvic fin attaches to the acetabulum of the pelvic girdle. There is a small iliac process that is akin to the scapular process of the pectoral girdle. In bony fish, the pelvic girdle remains free of the axial skeleton, similar to the condition in sharks. A puboischiac bar fuses the left and right pelvic girdles. The pelvic bone or cartilage to which the pelvic fin is attached is the basipterygium.

Tetrapods

The tetrapod pelvic girdle is attached directly to the vertebrae and composed of a dorsal ilium, a caudo-ventral ischium, and a cranio-ventral pubis. The pubes unite medially at the pubic symphysis, and the ischia often unite medially to form an ischial symphysis. All three bones—ilium, ischium, pubis—participate in the acetabulum.

Amphibia

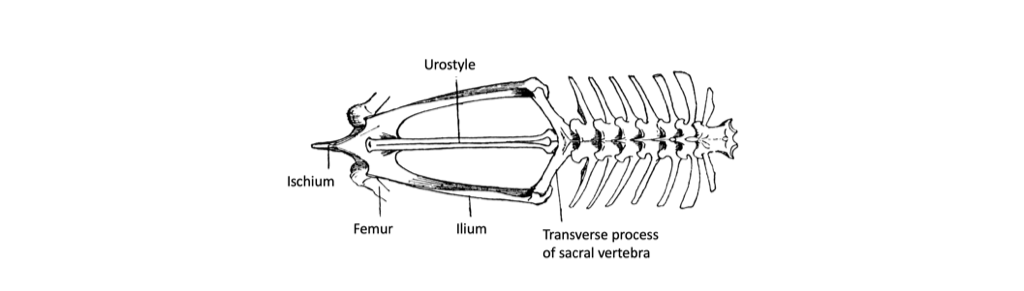

Salamander pelvic girdles have puboischia with a median symphysis and iliac processes that contact the transverse processes on the single sacral vertebra. Some aquatic salamanders lack hind limbs and the pelvic girdle. The anuran pelvic girdle is specialized: the ilium is long, and it attaches anteriorly to the transverse process of the sacral vertebra; the ischium and pubis are small but participate in the acetabulum; and the urostyle forms a second articulation between the vertebral column and the pelvic girdle.

Figure 7.4. Dorsal view of a frog vertebral column and pelvic girdle, with the urostyle blocking the pubis. Illustration modified from Thomson (1916, fig. 313), original under CC0 public domain.

Testudines

In pleurodires, the pelvic girdle fuses with the carapace; in cryptodires, it does not. Ventrally, turtles have a puboischiadic plate with pubic, ischial, and pubosichial symphyses. Anterior to the pubes, there is an unpaired, cartilaginous epipubis.

Squamates

Squamate pelvic girdles possess the typical os coxa comprised of three bones (ilium, ischium, pubis), and they have pubic and ischial symphyses. Some lizards can run bipedally and may have a pronounced preacetabular process. Snakes generally lack limb girdles, but a few groups retain vestiges.

Crocodylia

In Crocodylia, each os coxa is fused, and these two so-called innominate bones are joined by an ischial symphysis. The pubes are reduced, and epipubic bones project ventrally. Epipubic bones may be labeled “pubis” because some authors believe that they are the true pubes, even though they do not participate in the acetabulum.

Aves

In birds, the os coxa is formed by the ilium, ischium, and pubis, but the ilium fuses with sacral vertebrae to form a synsacrum. The synsacrum is rigid but light. Usually there is no pubic or ischial symphysis, permitting the passage of large eggs.

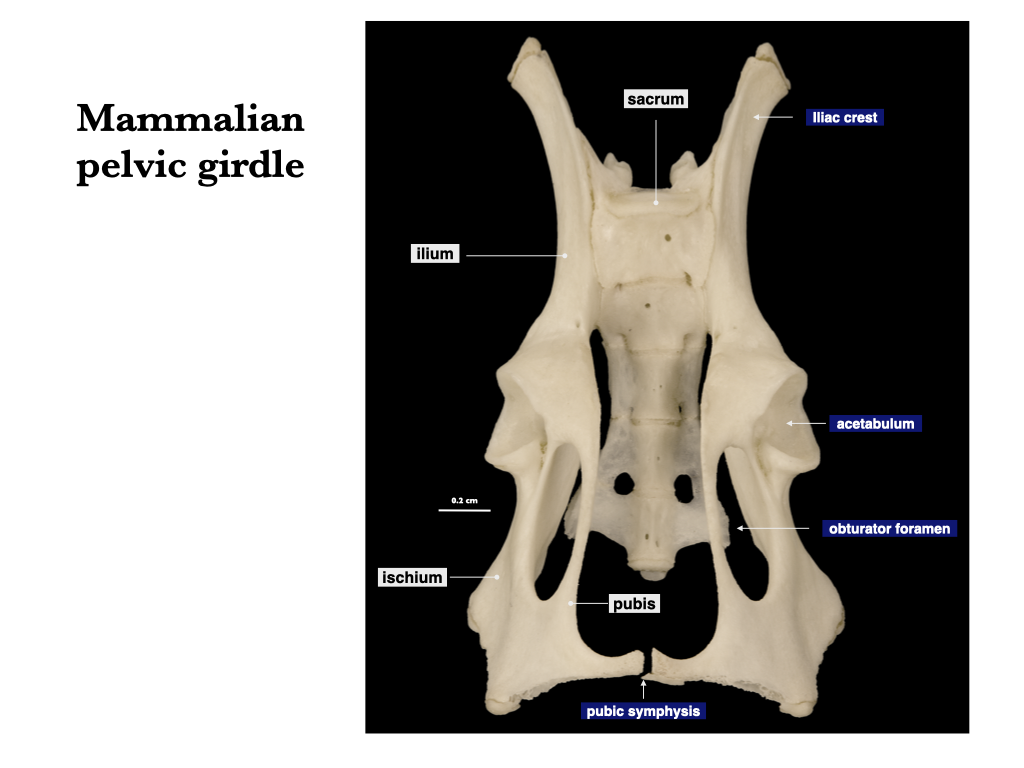

Mammalia

In mammals, the os coxa is formed of the fused ilium, ischium, and pubis. There may also be an acetabular or cotyloid bone in the acetabulum. The two ossa coxae are usually fused to each other at a pubic symphysis and sometimes also at an ischial symphysis. There is a large obturator foramen, bounded by the pubis and the ischium. Marsupials and monotremes have extra endochondral bones anterior to the pubes. These are called epipubic or marsupial bones, although they are probably not homologous with the epipubic bones of lizards, turtles, and crocodilians.

Figure 7.5. Pelvis of a small mammal, ventral view. Male geomyid specimen, MVZ 1500.