1 Vertebrate Skeleton

Objectives

- Gain skill in identifying skeletal regions, elements, and features.

- Learn appropriate terminology for describing anatomical features as well as their relative positions and orientations.

Overview

This lab will introduce you to the vertebrate skeleton and the terms that are used when working with major skeletal elements. After this lab, you should be able to identify and orient the objects listed in Terms 1.1. For this lab and all future labs, you will need to be able to identify and orient all objects in the terms list indicated in bold face. We recommend that you practice with the objects in articulation with the rest of the skeleton as well as with the objects in isolation.

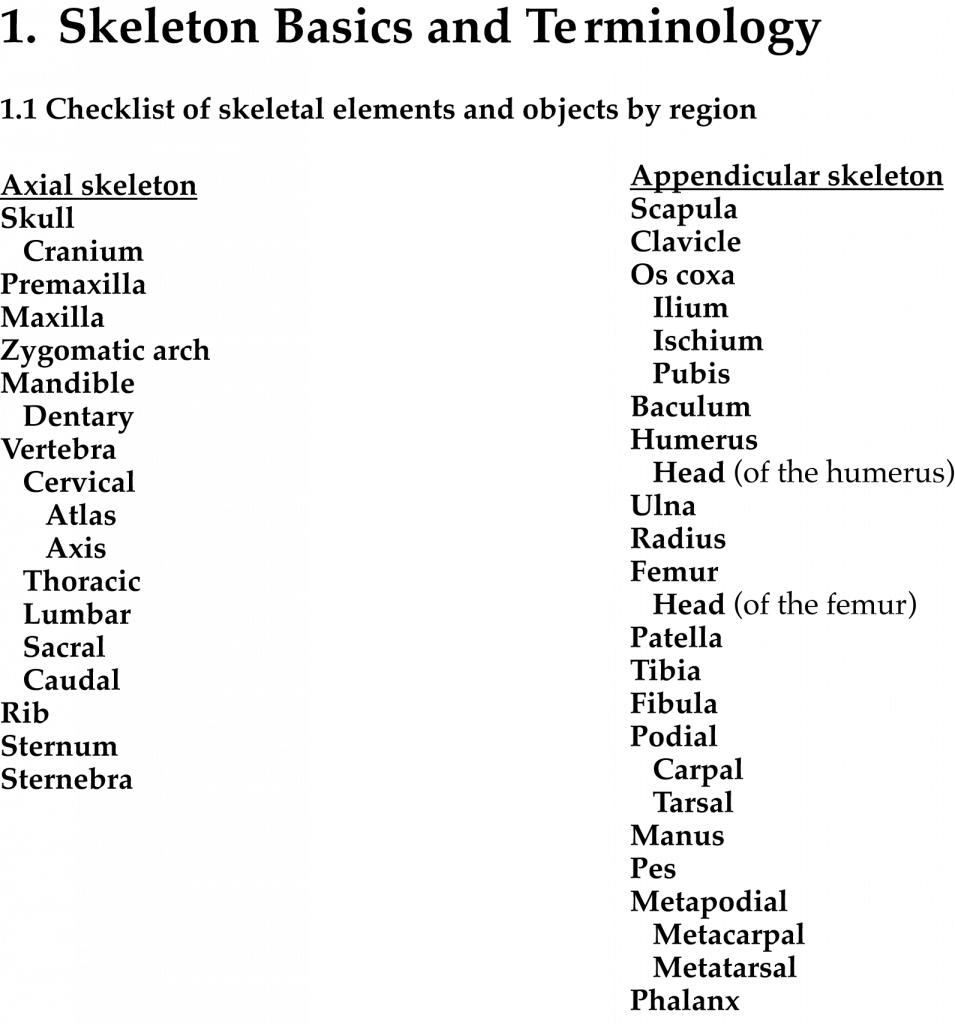

See the terms list here: Terms 1.1

Conventions for identifying morphological objects

Singular versus plural

Most anatomical terms are derived from Latin or Greek, and the conversion from singular to plural follows the conventions of these languages. Typically, the last letter of the singular form of the word, or the last few letters, are replaced in the plural form. It is important to use the correct words to describe anatomical objects to prevent confusion.

Singular, Plural

Fibula, Fibulae; Maxilla, Maxillae; Scapula, Scapulae; Tibia, Tibiae; Ulna, Ulnae; Vertebra, Vertebrae

Singular, Plural

Humerus, Humeri; Ischium, Ischia; Ilium, Ilia; Femur, Femora; Phalanx, Phalanges; Radius, Radii; Pubis, Pubes

Similar names for different things

Sometimes two distinct bones share a similar name. For example, the fibula and the fibulare are different bones, but they have similar names. Be sure to spell things correctly so that your communications are clear. Some bones with different names share common features that are named similarly. For example, as you see in the terms list, both the humerus and femur have a “head.” It is good practice to use a complete name for such features, e.g., “head of the humerus” (or humeral head) and “head of the femur” (or femoral head).

Different names for the same thing

Homologous bones and structures may be referred to by different names. There are a few possible reasons for this, and each case is different. The names of bones used by medical anatomists for human bones and features are often different from those used by scientists for non-human mammals. Often times, the name of an object in one clade is different from the name used by specialists working on another clade, because the names of the objects were created before a homologous relationship was discovered and described. You will likely encounter such cases throughout the course in your reading and from your instructors.

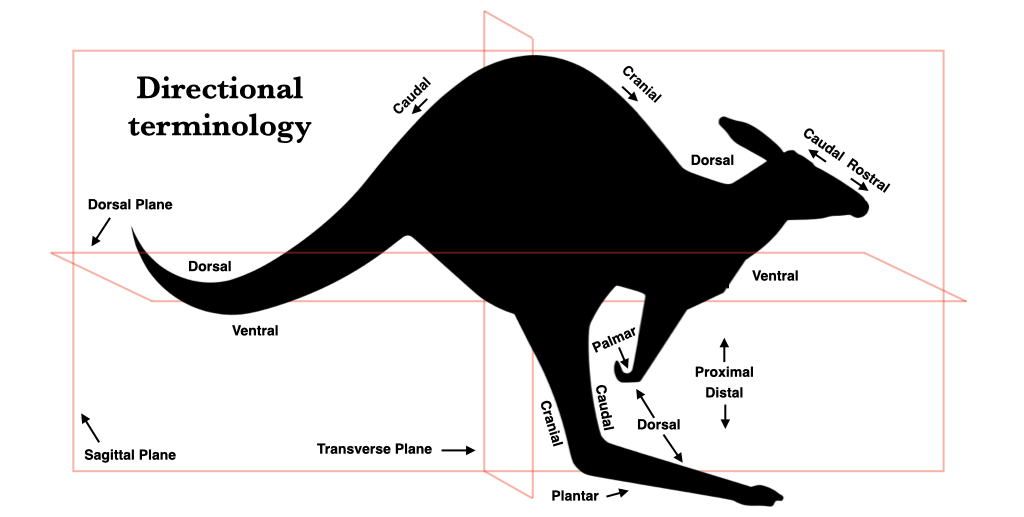

Orientation and relative position

As a morphologist, you need to be able to describe both the position and the orientation of skeletal elements. To do this, it is important to be able to describe directionality within the body as a whole. We first do this by establishing three anatomical planes that are all oriented 90 degrees relative to each other. We then assign terms to describe the position of an object relative to these planes. Below are the three planes and the associated positional terms.

Sagittal plane: A plane that defines the left and right sides of the body. If the sagittal plane separates the body into symmetrical left and right halves, it is called the mid-sagittal plane. The following terms describe position in relation to the mid-sagittal plane:

Median: On the midline of the body.

Medial: Toward the midline of the body.

Lateral: Away from the midline of the body.

Transverse plane: A plane that defines the relative position along the spine. The transverse plane divides the body into cranial and caudal portions; or, in humans, who are upright bipeds, into superior and inferior portions.

Cranial: Toward the head. Also called anterior (except in humans where it is called superior) and rostral (when the frame of reference is the cranium itself).

Caudal: Toward the tail. Also called posterior (except in humans where it is called inferior).

Frontal plane (also called the dorsal plane or coronal plane): A plane that describes position in relation to the belly or the back.

Ventral: Toward the belly. In humans, also called anterior.

Dorsal: Toward the back. In humans, also called posterior.

On the next page is a diagram of a kangaroo (macropodid) that illustrates these planes, these directions, and a few additional standard terms, such as:

Distal: Further away from a reference point (usually in relation to the axial skeleton).

Proximal: Closer to a reference point (usually in relation to the axial skeleton).

There are also a few terms that are specific to the manus (hand) and pes (foot).

Palmar: Toward the surface of the palm side of the hand.

Dorsal: Toward the back side of the hand (away from the palm).

Plantar: Toward the bottom (sole) of the foot.

Dorsal: Toward the top of the foot (away from the sole).

Figure 1.1. Directional terminology for communication of position around the vertebrate body. Note that some of these terms have different implications for an upright biped such as a human. Kangaroo silhouette from pixabay under CC0 Public domain.

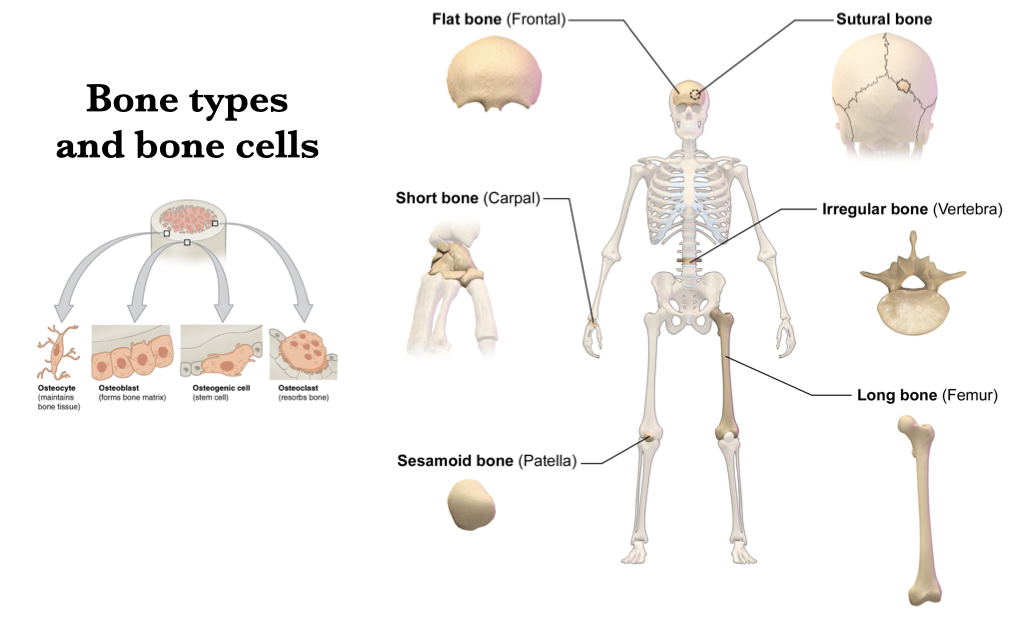

Figure 1.2. Informal characterization of the basic types of bone (right) and bone cell (left) in the vertebrate body, as illustrated by a human. Illustration of bone types (right) from Wikipedia user BruceBlaus under CC BY 3.0; illustration of bone cells (left) from Wikipedia user OpenStax College under CC BY 3.0.

Figure 1.2. Informal characterization of the basic types of bone (right) and bone cell (left) in the vertebrate body, as illustrated by a human. Illustration of bone types (right) from Wikipedia user BruceBlaus under CC BY 3.0; illustration of bone cells (left) from Wikipedia user OpenStax College under CC BY 3.0.

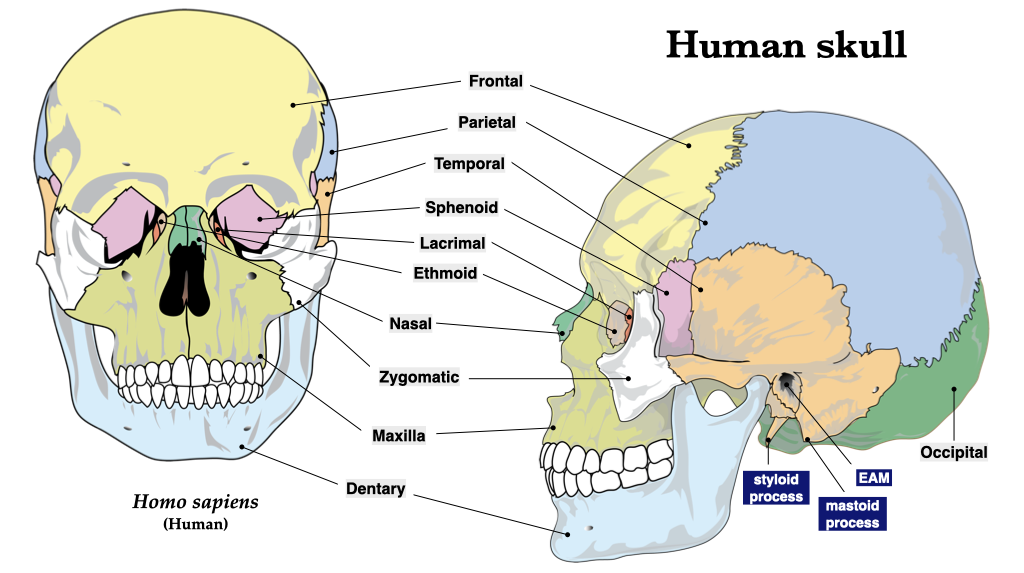

Figure 1.3. Human skull bones in frontal (left) and lateral (right) views. Illustration from Wikipedia user LadyofHats Mariana Ruiz Villarreal under CC0 public domain.

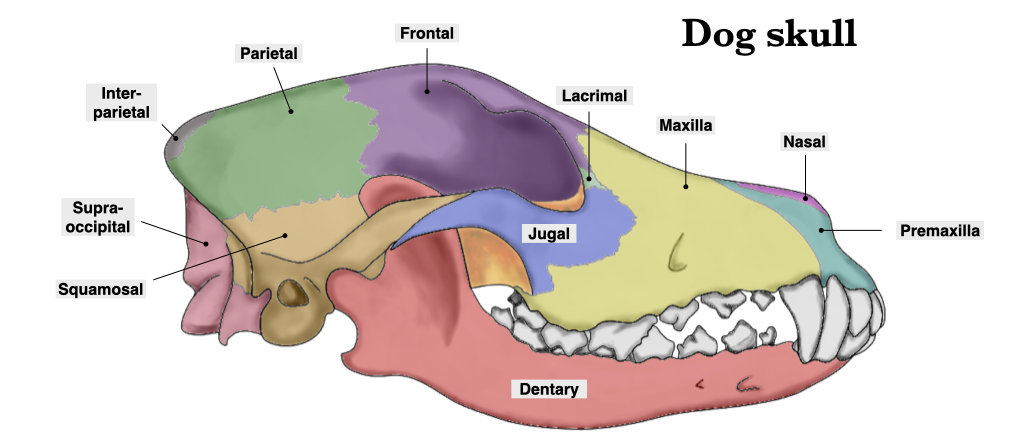

Figure 1.4. Dog skull bones, lateral view. Dog skull from Wikipedia user Przemek Maksim under CC BY-SA 3.0.

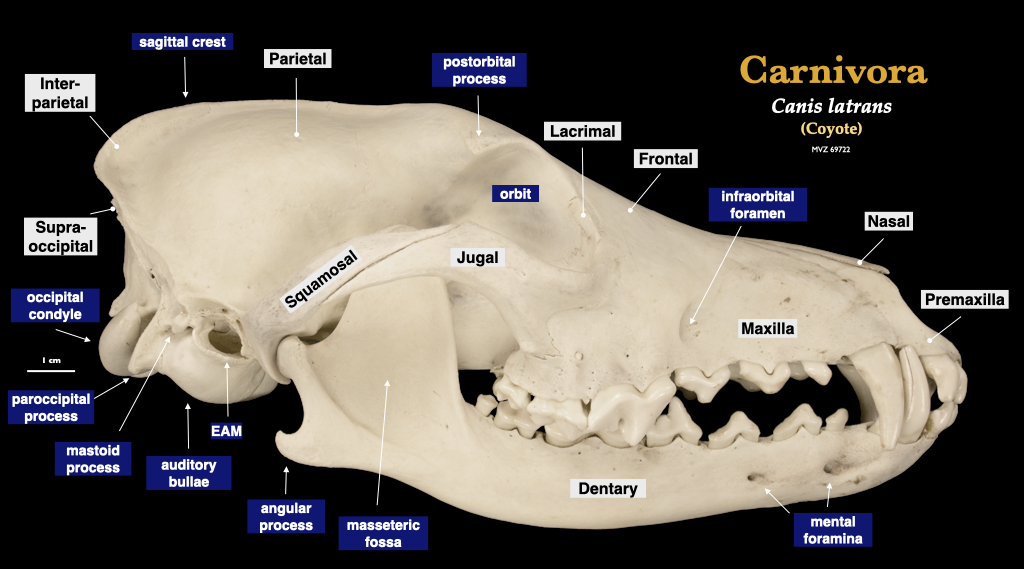

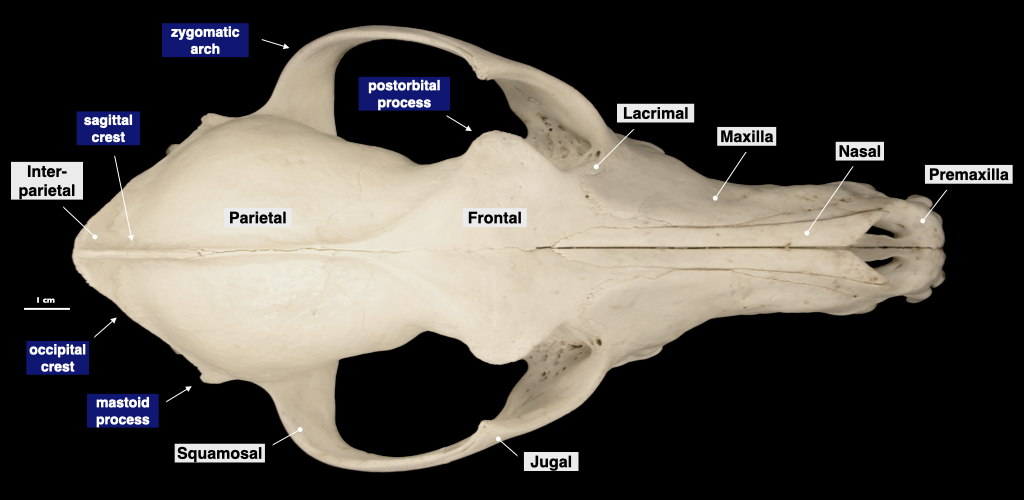

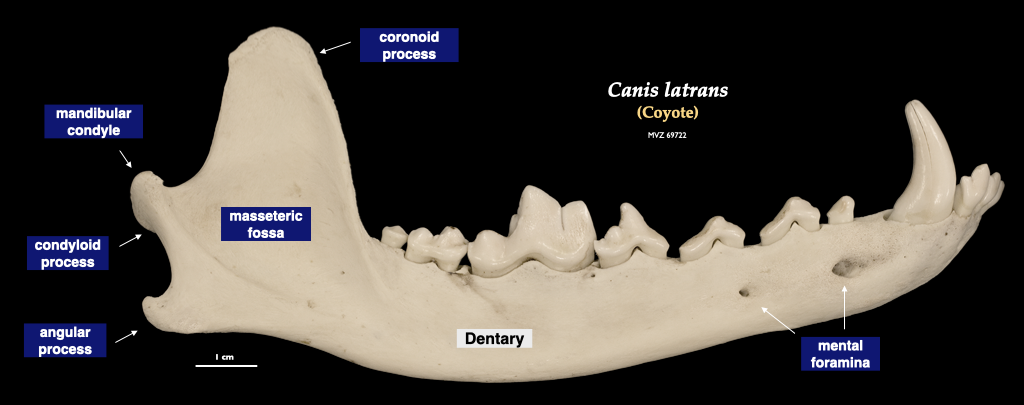

Figure 1.5. Skull of a coyote (Canis latrans, MVZ 69722) in lateral view (top) and cranium in inferior view (bottom).

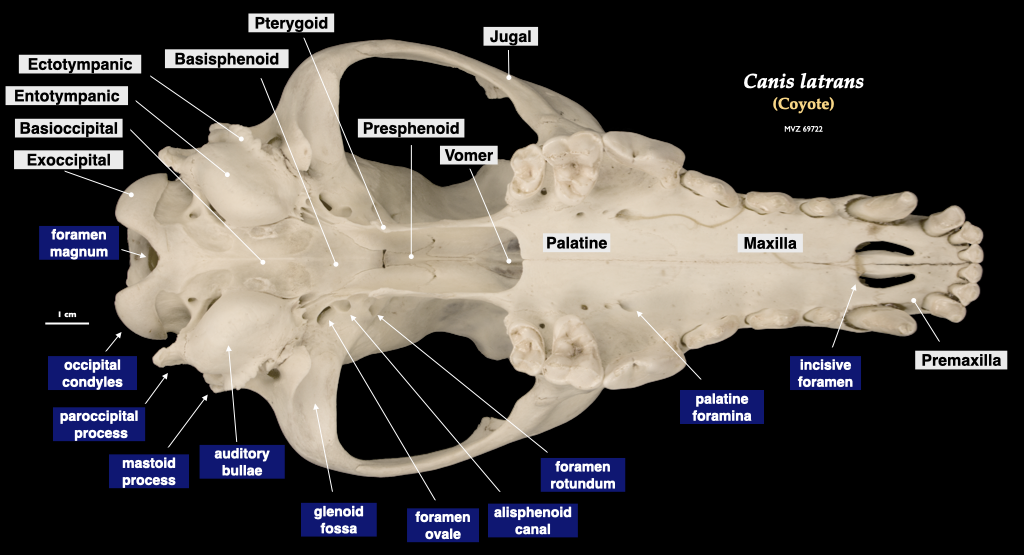

Figure 1.6. Cranium of a coyote (Canis latrans, MVZ 69722) in superior view (top) and mandible in lateral view (bottom).

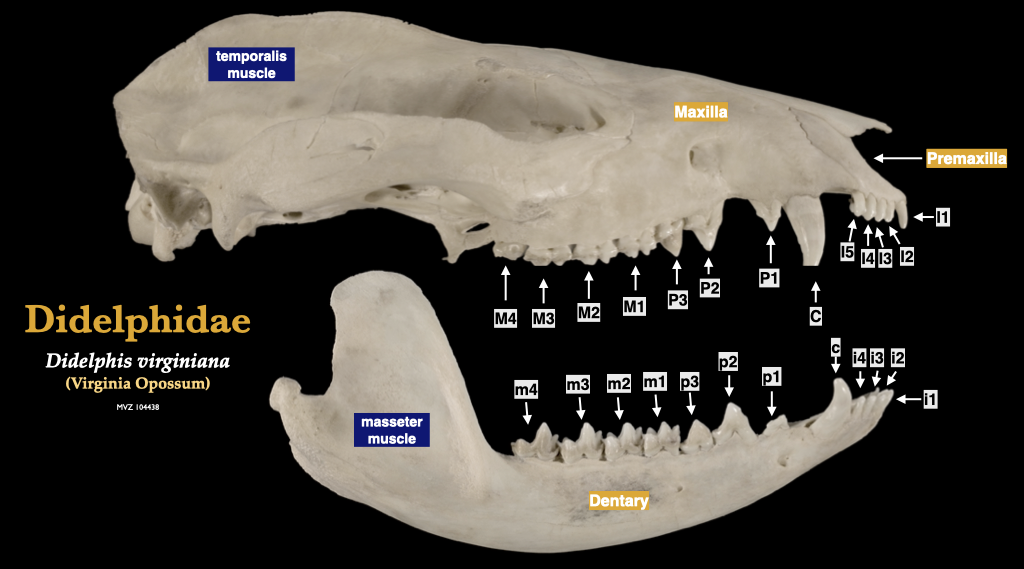

Tooth types and abbreviations

Teeth are of major importance for most vertebrates, and we will make a close study of the teeth of heterodont mammals. The four major tooth types— incisor, canine, premolar, molar—are abbreviated by the first letter, with an uppercase letter for the maxillary teeth (I, C, P, M) and lower-case letters for the mandibular teeth (i, c, p, m). Within each dental type, a number is used to indicate the tooth’s position, from mesial to distal (see figure below). The positional number may be given as a superscript to refer to a maxillary tooth or as a subscript to refer to a mandibular tooth. In this way, use of an upper-case letter and a superscript (e.g., M3) is redundant, but it is very clear. In diphyodont vertebrates, such as the mammals, a set of baby or deciduous teeth is replaced by a set of permanent or adult teeth. Tooth abbreviations are assumed to represent permanent teeth unless indicated as deciduous by a lower case “d” before the standard abbreviation (e.g., dP2).

Figure 1.7. Tooth names and abbreviations, illustrated by the common opossum (Didelphis virginiana, MVZ 104438).

Skeleton diagrams

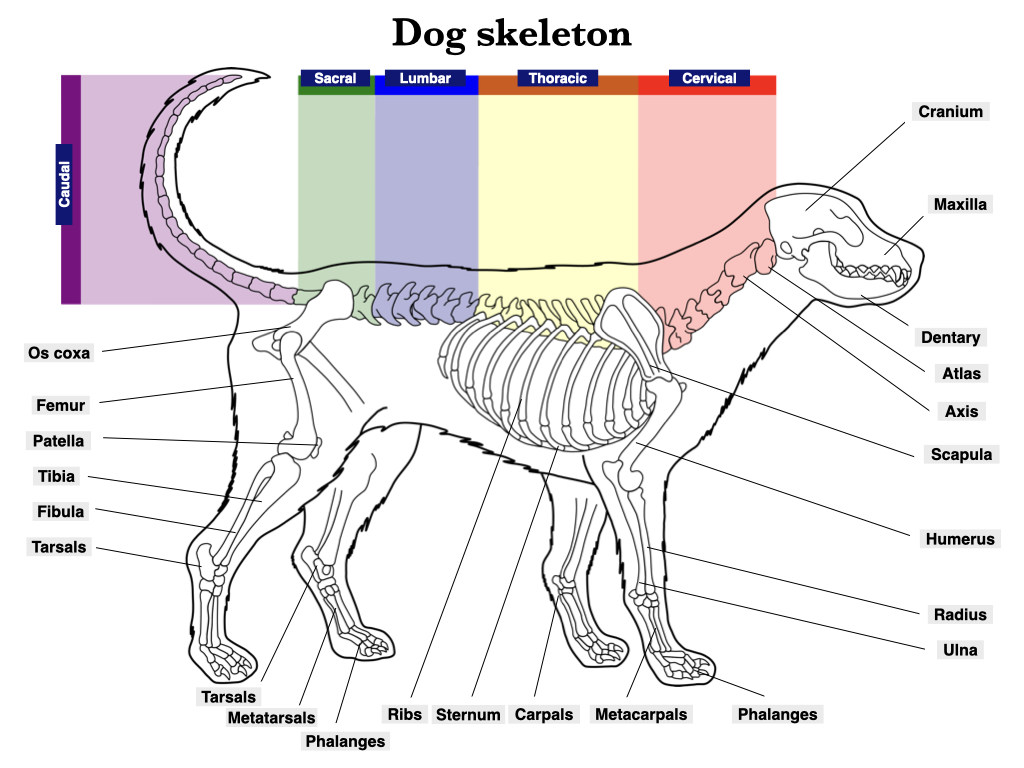

In your first lab, you will study both articulated and disarticulated skeletons of domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) and coyotes (Canis latrans), you will learn to identify all of the larger elements of the dog skeleton, and you will gain the ability to orient these bones and distinguish left from right for the paired bones. The objects that you need to know are listed in the table below, and you should practice orienting bones with the directional terminology in relation to the anatomical planes.

Please do not allow the specimens to become mixed. Although most of the specimens have numbers printed on them, not all of them do, and it takes a long time to reassemble skeletons that are mixed. Notify us if you cannot find the home of a wayward specimen, or if you find a specimen that does not have a number.

The bones that you need to know are labelled in the diagram below, but you do not need to know all of the labelled bones, so refer to the table below for guidance. The diagrams will help you to identify the bones in this lab, and they will be useful when studying outside of lab. You will also have access to unlabeled figures on which to practice your identifications and descriptions.

Figure 1.8. Major elements of the vertebrate skeleton and the five regions of the vertebral column. The base illustration of the dog skeleton from Wikipedia user Przemek Maksim under CC BY-SA 3.0.