63 Classical Chinese

題名雁塔代有其人

In every generation there are those who inscribe

their names on the Wild Goose Pagoda.

In 629, the Buddhist monk Xuanzang journeyed to the west in search of religious texts. Sixteen years later he returned to the Tang capital at Chang’an (modern Xi’an) with hundreds of Sanskrit sutras that would have to be rendered into Chinese. Emperor Gaozong invited the monk to base his translation project at the Big Wild Goose Pagoda on the grounds of Ci’ensi, a temple with strong ties to the throne and accordingly adorned with religious sculpture and textual engravings of the highest quality.

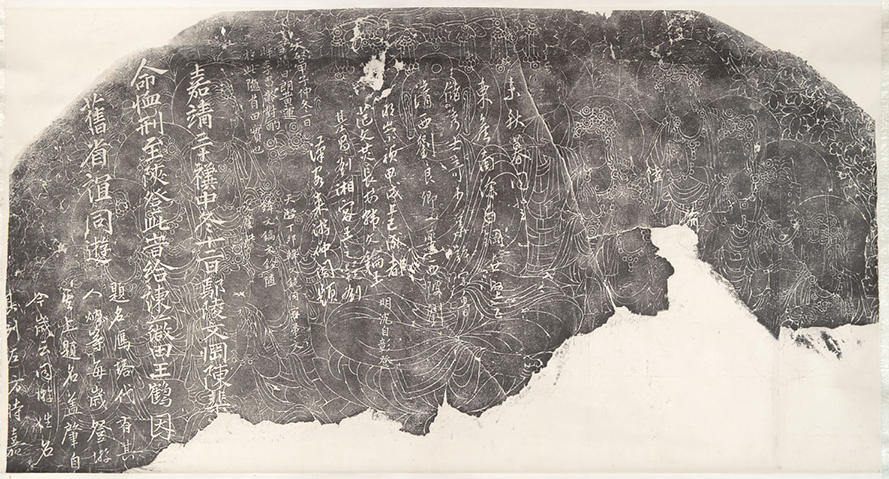

At that time, successful civil-service examinees were known to write their names on the pagoda walls with brush and ink. This custom evolved into something more durable in the centuries following the dynasty’s collapse in 907. Chang’an then lost its preeminence and much of its population, although it remained a site of historical and cultural interest. Visitors invariably stopped at the pagoda to view the surroundings from its upper stories. Some left their autographs there as well, carved over the Buddhas and divine attendants in the lintels surmounting the four entrances to the building — a practice that might have alluded to past privilege and accomplishment, but also to the city’s diminished status and the uncertain course of power.

This rubbing and dozens of others were given to the East Asian Library by the bequest of Woodbridge Bingham (1901–86), professor of history and founder of the Institute of East Asian Studies. Before the establishment of the East Asian Library, the campus community depended on faculty like Bingham, Ferdinand Lessing, and Delmer Brown, to help develop its collections: they left for sabbaticals abroad with lists of desiderata; once overseas, they sacrificed research hours haunting bookstores, searching out collectors willing to sell, wrangling with customs officials. At the end of their careers, many left their own collections to the university, building on the foundation that they had helped lay.

Contribution by Deborah Rudolph

Curator, C. V. Starr East Asian Library

Title: Dayan ta fo ke ji ti ming 大雁塔佛刻及題名

Title in English: Reliefs and inscriptions from the lintels of the Big Wild Goose Pagoda

Authors: Anonymous (artwork); multiple authors (textual inscriptions)

Imprint: 20th-century rubbing of Tang dynasty pictorial relief, with textual inscriptions dating from the Song through the Ming dynasties

Language: Chinese

Language Family: Sino-Tibetan

Source: C. V. Starr East Asian Library (UC Berkeley)

URL1: http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/stonerubbings/ucb/images/brk00024200_32b_k.jpg

URL2: http://digitalassets.lib.berkeley.edu/stonerubbings/ucb/images/brk00024198_32b_k.jpg

Other online editions:

- The East Asian Library’s rubbings of the lintels have been digitized and added to its online catalog of the rubbings collection, at http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/EAL/stone/index.html

- A series of photographs and details of the reliefs can be found on the blog site sina.com, at http://blog.sina.com.cn/s/blog_91ea73640102x92v.html (accessed 6/1/20)