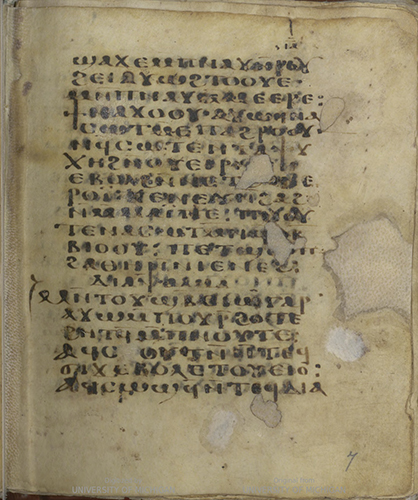

70 Coptic

Coptic Christians constitute the largest indigenous Christian community in the Middle East, concentrated primarily in Egypt, but more recently extending to growing diaspora communities in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Australia. The vast majority of Coptic Christians are members of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, one of the six Oriental Orthodox churches that was outcast by other Christian churches as a result of theo-political disputes during and following the Council of Chalcedon in 451 CE. The Coptic language has been a source of communal belonging for Egyptian Orthodox Christian communities, and of special concern to Orientalists of the modern period interested in the ancient languages of the Middle East.

Fundamentally, Coptic is the last written phase in the evolution of the language of the ancient Egyptians. The Coptic language may therefore be defined as the late Egyptian vernacular inscribed in the Greek alphabet, to which are juxtaposed multiple additional characters from demotic that number seven in the current surviving dialect, Bohairic. The rapid spread of Christianity in the fourth and fifth centuries CE influenced how and in what form Coptic was transmitted. Christians, in their missionary approach, revived the use of the local vernacular dialects. They primarily served as vehicles for transmitting Scripture. There are six major dialects of Coptic: Sahidic, Bohairic, Fayyumic, Akhmimic, Lycopolitan, Mesokemic, with multiple subdialects or minor ones.1

Early on, the language was primarily a translation tool for Christian literature originally written in Greek, such as the Scriptures; as well as a mechanism to mask the heterodox literature of Gnostic and Manichean communities from the eyes of agents of the Orthodox authorities in Alexandria. Following the Great Persecutions of the early fourth century, known as the “Era of the Martyrs,” two large-scale changes took place: the accelerated Christian conversion of the Egyptian countryside and the rapid growth of monasticism. These changes helped to elevate and expand the role of Coptic from a mode of translation to a complete literary language.2 Following the Arab Conquest of Egypt, Arabic slowly took precedence as a language of government and administration, and became the lingua franca of literary composition among the elite Copts of the time a few centuries later. Consequently, Coptic literature became restricted to hagiographic and liturgical compositions. Even hagiographic works were adapted for liturgical use.

Coptic persisted as a spoken and liturgical language until approximately the 13th century which was marked by the emergence of native scholars who composed Coptic grammars in Arabic as well as Arabic-Coptic dictionaries to help preserve the language. Among these were Aulad al-‘Assal and Abu al-Barakat ibn Kabar who flourished under the rule of the Fatimid and Ayyubid dynasties of Egypt.3 Nevertheless, Coptic steadily declined, but European travelers to Egypt of the 17th and 18th centuries would briefly note the continuance of the language among Copts in Upper Egypt.4 5 Preeminent Coptologist Hany Takla (2014) of the Saint Shenouda the Archimandrite Coptic Society has called the period between the 15th and 18th centuries the “dormant stage,” whereby the use of Coptic was at an all-time low. Through Orientalist and colonial influence, as well as Coptic initiative, a revival took place in the mid-19th century where the essence of reform was to “modernize” the Coptic language through its standardization. Historian Paul Sedra has argued that educated Copts initiated processes of textualizing Coptic heritage, and advocated for reform’s civilizing and disciplinary capacity.6

During fieldwork between 2014-2015 at the Coptic Cathedral in Cairo, I sat in on a number of Coptic language courses. One of the central drivers of Coptic language retention like these courses has been the institutional authority of the Coptic Orthodox Church. Church sponsorship has been vital in reintroducing Coptic classes in order to familiarize Coptic youth with liturgical terminology as well as cultivate a living heritage among contemporary Egyptian Orthodox Christians. Anthropologist Carolyn Ramzy has examined the continued importance of Coptic language to identity in 20th and 21st century Egypt and within its contemporary diasporas through the lens of church hymnody known as alḥān. Before the Sunday School movement of the early 20th century, Coptic Orthodox worship was largely limited to Church services, where parishioners traditionally practiced all of their official church rites accompanied by alḥān. As alḥān texts are in Coptic, few people — clerics, and educated cantors and laymen — sung and understood the genre. (Although, Coptic literacy in general declined at a faster rate in Lower Egypt than in Upper Egypt.) In the push for reform, though, parishioners increasingly joined Orthodox liturgical services in song, along with educated cantors and clergy. With the rise of digital archives, alḥān have become more widely sung and broadly understood by deacons and choirs, as well as laity in Egypt and in diaspora.7 The Coptic Orthodox Church in Egypt has emphasized the importance of alḥān as an integral part of Coptic heritage and a means to claim indigeneity — to distance Copts from Western missionary and contemporary political efforts at structural and cultural transformation.8

As diaspora communities have grown, discussions of the necessity of Coptic language to the Alexandrian Rite of Orthodox Christianity — in its hymns and liturgical practice — have been ongoing, as the Coptic Orthodox Church expands and seeks to evangelize outside of Egypt’s national boundaries.9 For all intents and purposes, the Coptic language is a “dead” language — one not in vernacular use today. Instead, the Coptic language is kept alive through liturgical practice and the academic field of Coptology. Language preservation in the Coptic community has historically been about community preservation. During my own dissertation research between Egypt and the United States, Copts described extinction of the Coptic vernacular as a “failure of the community.” For those in the diaspora, studying Coptic, whether at a theological seminary or through local parishes, has forged a new kind of ethos — leaving behind the physical place of Egypt as a space of belonging.

The retention of Coptic in the United States has taken on the language of survival. At the 2014 North American Mission and Evangelism Conference (N.A.M.E.) in Florida, one diaspora priest described the importance of language to communal belonging in Egypt in this way: “We were fighting for our survival. The Church became a haven for the culture, spirituality, etc. Once the Ottoman empire weakened and the missionaries came to Egypt, the Coptic Church created a defense mechanism that has been carried over with our immigration leading to…an island. The belief that we have to teach people the language and culture in order to survive….”10 Many in the Coptic diaspora have contended with the continued liturgical use of the Coptic language, debating whether it is the role of the Church to hold the remaining remnants of Coptic language’s persistence among this transnational community. Yet, the language’s significance continues to be pregnant with meaning.

As poet Matthew Shenoda writes:

Time a question

only the Nile can answer

meandering through papyrus fields & baqara expanse

her sediment the testament of Coptic11

The Coptic language, while now secluded to liturgical and academic circles, still maintains communal importance in Egypt and in diaspora as a mode of perseverance and sedimented belonging.

Contribution by Candace Lukasik

PhD, Department of Anthropology

Postdoctoral Fellow, Washington University in St. Louis

Sources consulted:

- Rodolphe Kasser. “Language(s), Coptic.” In Coptic Encyclopedia, 8 vols. Edited by Aziz S. Atiya. New York: Macmillan, 1991.

- Hany Takla. “The Coptic Language: The Link to the Ancient Egyptians.” In The Coptic Christian Heritage: History, Faith, and Culture. Edited by Lois M. Farag. London: Routledge, 2014.

- Samuel Moawad. “Coptic Arabic Literature: When Arabic Became the Language of Saints.” In The Coptic Christian Heritage: History, Faith, and Culture. Edited by Lois M. Farag. London: Routledge, 2014.

- H. Worrell. A Short Account of the Copts. Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press: Oxford University Press, 1945.

- Aziz S. Atiya. History of Eastern Christianity. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1968.

- Paul Sedra. From Mission to Modernity: Evangelicals, Reformers, and Education in Nineteenth Century Egypt. London: Bloomsbury, 2011.

- Carolyn Ramzy. “Autotuned Belonging: Coptic Popular Song and the Politics of Neo-Pentecostal Pedagogies.” Ethnomusicology 60(3), 2016.

- Heather Sharkey. American Evangelicals in Egypt: Missionary Encounters in an Age of Empire. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

- Nicholas Ragheb. “Coptic Ethnoracial Identity and Liturgical Language Use.” In Contemporary Christian Culture: Messages, Missions, and Dilemmas. Edited by Omotayo O. Banjo and Kesha Morant Williams. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2018.

- Michael Sorial. Incarnational Exodus: A Vision for the Coptic Orthodox Church in North America. Washington D.C.: St. Cyril of Alexandria Society Press, 2014.

- Matthew Shenoda. Somewhere Else. Minneapolis: Coffee House Press, 2005.

Author: unknown

Imprint: 6th century

Edition: n/a

Language: Coptic

Language Family: Afro-Asiatic, Egyptian

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (University of Michigan)

URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015094345017