54 French

Si c’est ici le meilleur des mondes possibles, que sont donc les autres?

If this is the best of all possible worlds, what are the others like?

— Voltaire, Candide, ou, l’Optimisme (trans. Burton Raffel)

Voltaire, né François-Marie Arouet (1694-1778), was a French philosopher who mobilized the power of Enlightenment principles in 18th-century Europe more than any other thinker of his day. Born into a prosperous bourgeois Parisian family, his father steered him toward law, but he was intent on a literary career. His tragedy Oedipe, which premiered at the Comédie Française in 1718, brought him instant financial and social success. A libertine and a polemicist, he was also an outspoken advocate for religious tolerance, pluralism and freedom of speech, publishing more than 2,000 works in all possible genres during his lifetime. For his bluntness, he was locked up in the Bastille twice and exiled from Paris three times.1 Fleeing royal censors, Voltaire fled to London in 1727 where he, despite arriving penniless, spent two and a half years hobnobbing with nobility as well as writers such as Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift.2

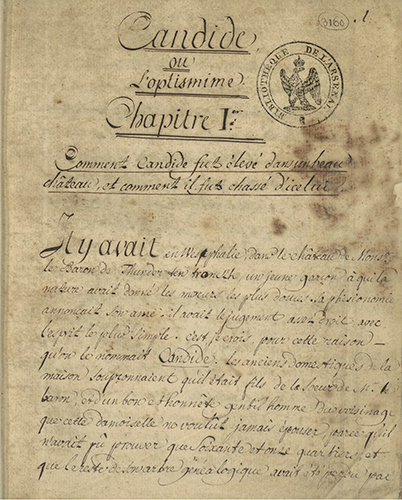

After his sojourn in Great Britain, he returned to the Continent and lived in numerous cities (Champagne, Versaille, Amsterdam, Potsdam, Berlin, etc.) before settling outside of Geneva in 1755 shortly after Louis XV banned him from Paris. “It was in his old age, during the 1760s and 1770s,” writes historian Robert Darnton, “that he wielded his second and most powerful weapon, moral passion.”3 Early in 1759, Voltaire completed and published the satirical novella Candide, ou l’Optimisme (“Candide, or Optimism”) featured in this entry. In 1762, he published Traité sur la tolerance (“Treatise on Tolerance”), which is considered one of the greatest defenses of religious freedom and human rights ever composed. Soon after its publication, the American and French Revolutions began dismantling the social world of aristocrats and kings that we now refer to as the Ancien Régime.4

With Candide in particular, Voltaire is credited with pioneering what is called the conte philosophique, or philosophical tale. Knowing it would scandalize, the story was published anonymously in Geneva, Paris and Amsterdam simultaneously and disguised as a French translation by a fictitious Mr. Le Docteur Ralph. The novella was immediately condemned for its blasphemy and subversion, yet within weeks sold 6,000 copies within Paris alone.5 Royal censors were unable to keep up with the proliferation of illegal reprints, and it quickly became a bestseller throughout Europe.

Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) is considered one of its clearest precursors in both form and parody. Candide is the name of the naive hero who is tutored by the optimistic philosophy of Pangloss, who claims that “all is for the best in this best of all possible worlds” only to be expulsed in the first few pages from the opulent chateau in which he grew up. The story unfolds as Candide travels the world and encounters unimaginable human suffering and catastrophes. Voltaire’s satirical critique takes aim at religion, authority, and the prevailing philosophy of the time, Leibnizian optimism.

While the classical language of Candide is more than 260 years old, it is easy enough to comprehend today. As the lingua franca across the Continent, French was accessible to a vast French-reading public since gathering strength as a literary language since the 16th century.6 However, no language stays the same forever and French is no exception. Old French, which is studied by medievalists at Berkeley, covers the period up to 1300. Middle French spans the 14th and 14th centuries and part of the early Renaissance when the study of French language was taken more seriously. Modern French emerged from one of the two major dialects known as langue d’oïl in the middle of the 17th century when efforts to standardize the language were taking shape. It was then that the Académie Française was established in 1635.7 One of its members, Claude Favre de Vaugelas, published in 1647 the influential volume, Remarques sur la langue françoise, a series of commentaries on points of pronunciation, orthography, vocabulary and syntax.8

At UC Berkeley, scholars have been analyzing Candide and other French texts in the original since the university’s founding. The Department of French may have the largest concentration of French speakers on campus, and French remains like German, Spanish, and English one of the principal languages of scholarship in many disciplines. Demand for French publications is great from departments and programs such as African Studies, Anthropology, Art History, Comparative Literature, History, Linguistics, Middle Eastern Studies, Music, Near Eastern Studies, Philosophy, and Political Science. The French collection is also vital to interdisciplinary Designated Emphasis PhD programs in Critical Theory, Film & Media Studies, Folklore, Gender & Women’s Studies, Medieval Studies, and Renaissance & Early Modern Studies.

UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library is home to the most precious French holdings, including medieval manuscripts such as La chanson de geste de Garin le Loherain (13th c.) and dozens of incunables. More than 90 original first editions by Voltaire can be located in these special collections, including La Henriade (1728), Mémoires secrets pour servir à l’histoire de Perse (1745) Maupertuisiana (1753), L’enfant prodigue: comédie en vers dissillabes (1753) and a Dutch printing of Candide, ou, l’Optimisme (1759). Other noteworthy material from the 18th century overlapping with Voltaire include the Swiss Enlightenment and the French Revolutionary Pamphlet collections.

Contribution by Claude Potts

Librarian for Romance Language Collections, Doe Library

Sources consulted:

- Davidson, Ian. Voltaire. New York: Pegasus Books, 2010. xviii

- Ibid.

- Darnton, Robert. “To Deal With Trump, Look to Voltaire,” New York Times (Dec. 27, 2018).

- Voltaire. Candide or Optimism. Translated by Burton Raffel. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005.

- Davidson, 291.

- Levi, Anthony. Guide to French Literature. Chicago: St. James Press, c1992-c1994.

- Kors, Alan Charles, ed. Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment. Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Ibid.

Title in English: Candide, ou L’optimisme (La Vallière Manuscript)

Author: Voltaire, 1694-1778

Imprint: La Vallière (Louis-César, duc de). Ancien possesseur, 1758.

Edition: 1st edition

Language: French

Language Family: Indo-European, Romance

Source: Gallica (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, 3160)

URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8458202f/f9.item.r=candide%20la%20valliere

Other online editions:

- Candide, ou l’Optimisme , traduit de l’allemand de M. le docteur Ralph. Paris: Lambert, 1759. (Gallica)

- Candide, ou l’Optimisme. Première Partie 1. Édition revue, corrigée et augmentée par l’auteur. Aux Delices, 1763.(Gallica)

- Candide, ou l’Optimisme, traduit de l’allemand de M. le docteur Ralph. Seconde partie. Aux Delices, 1761. (Gallica)

- Candide ou L’optimisme. Préface de Francisque Sarcey; illustrations de Adrien Moreau. Paris: G. Boudet, 1893. (Gallica)

- Candide, ou, L’optimisme. Illustré de trente-six compositions dessinées et gravées sur bois par Gérard Cochet. Paris: Les Editions G. Crès et Cie, 1921. (HathiTrust)

- Candide, or Optimism. Translated into English by Burton Raffel. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005. (ebrary-UCB access only)

- Candide / Voltaire. [United States]: Tantor Audio: Made available through hoopla, 2006. ebook and audiobook (OverDrive-UCB access only)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Candide, ou, l’Optimisme / traduit de l’allemand de Mr. le docteur Ralph. Amsterdam: Marc-Michel Rey, MDCCLIX [1759].

- Candide, ou, L’optimisme. Édition présentée, établie et annotée par Frédéric Deloffre. Paris: Gallimard, 2003.

- Candide. [Graphic novel] Interventions graphiques de Joann Sfar. Rosny: Éditions Bréal, 2003.

- Candide, or Optimism. Translated and edited by Theo Cuffe with an introduction by Michael Wood. New York : Penguin Books, 2005.

- Candide, ou L’optimiste. [Graphic novel] Scénario, Gorian Delpâture & Michel Dufranne; dessin, Vujadin Radovanovic; couleur, Christophe Araldi & Xavier Basset. Paris: Delcourt, 2013.

- Candide or, Optimism: The Robert M. Adams Translation, Backgrounds, Criticism. Edited by Nicholas Cronk. New York : W. W. Norton & Company, 2016.