71 Indo-Persian

Starting with the Ghaznavid dynasty in the 11th century, various Persian-speaking Turkish elites extended their domain over South Asia until the language had its heyday during the mighty Mughal Empire, which during its zenith stretched across almost the entire Indian peninsula. Consequently, Persian not only became the language of the imperial court at Delhi but also of vassal kingdoms across the region, especially when it came to official record-keeping and correspondence. Simultaneously, it became the language of a pan-Indic high culture based on a Sufism tinged with broadminded Hellenistic philosophy that cut across confessional, ethnic, and political boundaries.

During these centuries India produced a number of prominent Persian poets. Many others flocked to the patronage of the sultans and emperors of India, often from Iran, especially after the forced imposition of Shiism by the Safavid sultans. While these immigrants kept the Indian users of Persian connected to the larger literary world of Persian, over time Indo-Persian developed its own distinctive flavor as the language interacted with local cultures and languages. Since the vast majority of Indians who used Persian did not have it as their mother tongue, Persian philology was largely developed in India. The cultural influence of the language was so deep that it continued to be cultivated for nearly a century after the 1830s when the East India Company formally replaced it as the language of administration with English and Hindustani (later called Urdu).

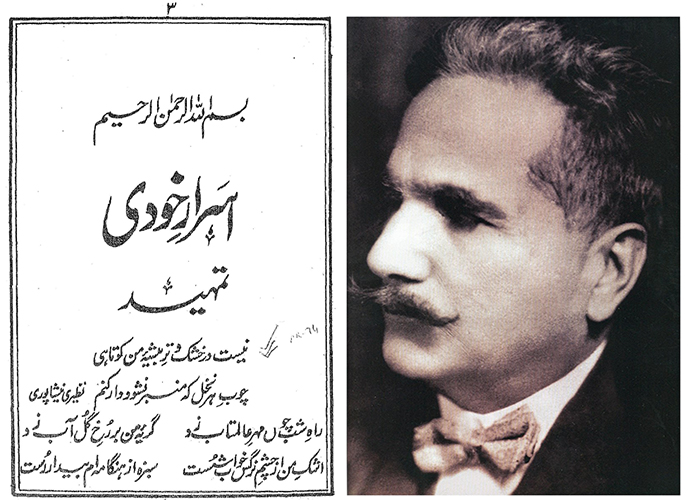

Certain Indo-Persian poets became widely popular throughout the Persian-speaking world. Among these were Amir Khusrow (ca. 1253-132), Abd al-Qadir Bidil (1644-1720), whose verses are still widely appreciated in Afghanistan and Tajikistan, and last but not least, Sir Muḥammad Iqbāl (1877-1938). Born in 1877 in Sialkot, Panjab, Iqbāl studied Persian and Arabic in his hometown before moving to Lahore and studying with Sir Thomas Arnold at Government College. He then went for higher education to the University of Cambridge in the UK and obtained a PhD in philosophy at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Germany. Iqbāl had long been an admirer of the Persian Sufi poet, Jalal al-Din Rumi, and in Europe was deeply influenced by the thought of Nietzsche, Goethe, and Bergson. He was knighted by King George V in 1922. On his return to British India, he began to teach philosophy and English literature at Government College in Lahore where he remained for the rest of his life and lies buried there.

With his deep knowledge of Perso-Islamic philosophy, Sufism, and key European thinkers of his time, Iqbāl set about charting a new course of thought and action for Indian Muslims. A proponent of Pan-Islamism, he was convinced that Muslims had lost sight of the original teachings and aims of their religious culture and had fallen into mystical navel-gazing and empty ritual. In order to reawaken them he resorted to setting out his new revolutionary ideas in the form of Persian (and later, Urdu) poetry.

Asrar-i khudi (Secrets of the Self) was his first book of poetry published in 1915. He preferred writing in Persian as it better expressed his philosophical ideas and also gave him a wider audience. As a mark of his devotion, he used the same poetic meter for his creation that was used by Rumi for his famous Masnavi. He also used the traditional vocabulary of classical Persian poetry but imbued it with new, modern meanings. With its call for resolute action and strongly developed individual personalities that revel in facing challenges, the book acted as a lightning-rod for the younger members of Iqbal’s generation while it courted controversy with older people because of its criticism of the Iranian poet Hafiz whose mystic-philosophical verses were considered the epitome of Sufism. Iqbāl accused him of ensnaring Muslims into the labyrinth of neo-platonic speculation and preaching a negation of the self by declaring it to be an illusion that was best lost by merging into the divine. Iqbāl declared such negation of the self as an affront to God as the self was his greatest gift to human beings and devaluing it sapped their strength to deal with life’s social and moral challenges.

Asrar-i khudi and its call for reappraisal and action became so popular in India and beyond, that the Cambridge orientalist Reynold A. Nicholson translated it into English in 1920. Iqbāl’s ideas were credited with the political awakening of Indian Muslims that culminated in the creation of Pakistan. Decades later, his ideas were to influence some major participants of the Iranian Revolution, in particular Ali Shariati. In many regards Iqbāl’s poetry was to be the swansong of the Indo-Persian literary tradition. While the latter has not died out completely, it does not have the vigor of former centuries. However, its last bright star turned out to be a supernova whose light is still illuminating the Islamic world.

In the Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies, Dr. Gregory Maxwell Bruce — Berkeley’s lecturer for Urdu — also offers courses on Indo-Persian texts.

Contribution by Adnan Malik

Curator and Cataloger for the South Asia Collection

South/Southeast Asia Library

Title in English: Secrets of the Self

Authors: Iqbāl, Sir, Muḥammad, 1877-1938.

Imprint: n.p, [1915].

Language: Indo-Persian

Language Family: Indo-European, Indo-Iranian

Source: The Internet Archive

URL: https://archive.org/details/AsraarEKhudi-AllamaIqbal/page/n1/mode/2up

Other online editions:

- Asrar-i-Khudi. Iqbal Academy Pakistan. (accessed 7/17/20)

- Asrar-i-Khudi. Iqbal Cyber Library. (accessed 7/17/20)

- The Secrets of the Self, English translation of Asrar-i-Khudi by Reynod Nicholson. Iqbal Academy Pakistan. (accessed 7/17/20)

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- Tarjumān-i Asrār-i khvudī / tafhīmī tarjamah, G̲h̲ulām Dastgīr Shahāb. Pūnah: Ẓafar Iqbāl: Milne ke pate, Salīqah Kitāb Ghar, 1989. Poems in Persian with Urdu translation.

- The Secrets of the Self = Asrar-i khudí: A Philosophical Poem / by Dr. Sir Muhammad Iqbal. Lahore: Muhammad Ashraf, 1964.

- The Secrets of the Self: English Rendering of Iqbal’s Asrar-i khudi / by Maqbool Elahi. Lahore: Iqbal Academy Pakistan, 1986.