13 Medieval Hebrew

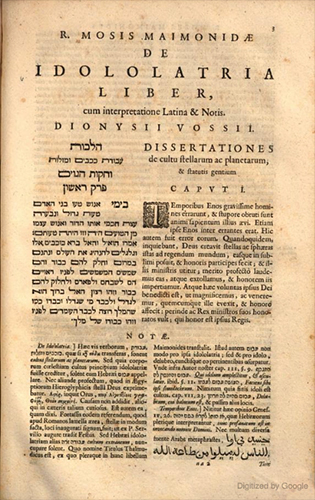

Dionysus Vossius’s Latin translation of Maimonides’s Laws of Idolatry, first published in 1642, is self-evidently the product of many cultures. On some pages, you can find four different alphabets: Hebrew, Latin, Arabic, and Greek. Yet the text itself aims to protect the singular, true religion from all other pretenders. A paradoxical work of cosmopolitan xenophobia, this version of “Laws of Idolatry” sheds light on the contradictions and complexities of 17th-century Christian Hebraism, and it places a canonical Jewish text in a surprising, unfamiliar context.

Maimonides had long been a favorite among Christians (“the only Jew to desist from talking nonsense,” as the scholar Joseph Scaliger wrote), and his philosophical masterpiece, The Guide to the Perplexed was translated to Latin in the thirteenth century. But his law codes remained more obscure. Only after Christian knowledge of and interest in Hebrew exploded in the sixteenth century did scholars begin mining them — for philological tidbits, interpretations of scripture, and mythographic lore. That’s because while the Laws of Idolatry mainly contains practical restrictions on Jewish interactions with idolaters, it also contains Maimonides’ capsule history of various forms of idolatry. This history and typology proved immensely important in a nascent scholarly discipline, what we would call today the comparative history of religion.

Dionysus Vossius, a Dutchman, was probably inspired to translate and annotate Maimonides by the great English scholar John Selden. Selden had used Maimonides to write De Diis Syriis, a comprehensive treatment of the pagan gods which heavily influenced John Milton’s Paradise Lost. Dionysus’s father Gerardus Vossius, himself a great scholar and friend of the Dutch jurist and historian Hugo Grotius, took Dionysus to England, where he met Selden and studied. Dionysus was a precocious scholar (he wrote an Arabic dictionary at sixteen), but he died at 21, and the Laws of Idolatry is consequently bound with his father’s complete works.

I am drawn to this volume by its incredible synthesis of religions and cultures: the English, Dutch, and Continental European republic of letters; the text’s many learned languages; the mixed Christian, Jewish, and pagan histories. To be sure, the combination is not without tension. The famous passage in which Maimonides proclaimed Christians idolaters (9:4) is of course absent here, as even in Hebrew it was a favorite target for Christian censors. And indeed, Vossius’s translation was itself banned, placed on the Catholic Church’s Index Librorum Prohibitorum in 1717. Yet there is a remarkable irony in this most avowedly parochial of books becoming a source of wisdom for Christian scholars. This odd jumble of languages, prejudices, agendas and mistakes is a little glimpse of early modern globalization; its yellowed pages contain a world that is shockingly interconnected, mixed-up, and vibrant. Leaf through the pages of the 1668 edition of De Idololatria Liber at UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, or read it online.

Contribution by Raphael Magarik

PhD Student, Department of English

Title in English: The Laws of Idolatry

Author: Maimonides, Moses, 1135-1204; Latin translation and notes by Dionysius Vossius

Imprint: Amsterdam: Joan Blaeu, 1668.

Edition: uncertain

Language: Medieval Hebrew

Language Family: Afro-Asiatic, Northwest Semitic

Source: Google Books (Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Roma)

URL: https://books.google.com/books?id=sZ4PtQEACAAJ&pg=PA1#v=onepage&q&f=false

Select print editions at Berkeley:

- R. Mosis Maimonidae De idololatria liber, cum interpretatione latina, & notis, Dionysii Vossii. Amsterdami: apud Ioannem Blaev, 1668. Bancroft Folio f BL200.V6 D3 1668 v.2