58 Syriac

— One of Socrates’ disciples asked him, “How come I never see in you

any sign of sorrow?” Socrates replied: “Because I don’t possess anything

that I would grieve over if it got lost!”

— Another philosopher was asked: “What is it that would benefit most

people?” He replied: “The death of an evil ruler.”

— A man saw in a dream that he was frying pieces of dung. So he went to

a dream-interpreter to get an explanation of the dream. The dream-

interpreter said to him, “If you give me a zuza [a small coin], I will

interpret it for you.” The man replied, “If I had a zuza, I would buy some

fish with it and fry them, instead of frying pieces of dung!”

— A woman asked her neighbor, “How come it is permitted for a man to

buy a hand-maiden for himself, and to sleep with her, and do whatever he

wants, while it is not permitted for a woman to do any of these things, at

least in public?” The neighbor said to her, “It is because kings, judges, and

law-makers have all been men, and so have been able to justify their

actions and oppress women.” (trans. E. A. Wallis Budge)

These four anecdotes come from a work entitled The Book of Entertaining Stories, written in the Syriac language. Syriac is a member of the Aramaic branch of the Semitic languages. It developed as an independent language around the city of Edessa, today’s Shanliurfa, in southeastern Turkey. The first Syriac inscription dates to the year 6 AD. Shanliurfa became a center of early Christianity, and over the next thousand years a wealth of literature was written in Syriac, including historical annals, scientific texts, medical manuals, philosophical and theological tractates, religious poetry, and Bible translations and commentaries. Because of the richness of theological literature written in Syriac, it is sometimes called the “third language of Christianity,” after Greek and Latin. Much of this knowledge still exists only in manuscript form, awaiting study.

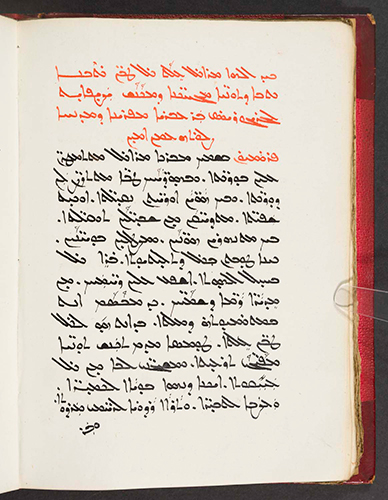

The earliest Syriac texts are in a recognizably Aramaic form of the Semitic alphabet, which was originally developed by the Phoenicians. As with all Semitic alphabets, it reads from right to left. As time went by, it took on its own distinctive form, appearing in three distinct “fonts.” The manuscript page reproduced here is in the “West Syriac” font. The original Phoenician alphabet indicated only consonants, not vowels, but Syriac developed different ways to indicate vowels. These take the form of small signs written either above or below the consonants. These are however only used sporadically. In the page illustrated here, the vowel marks were added by a different scribe than the one who wrote the consonantal text.

With the Arab-Muslim conquests of the Near East, starting in the seventh century AD, Syriac was gradually replaced by Arabic as a spoken language. By about 1300 AD, there were probably very few native speakers of Syriac. However, it continued in use as a written language, right up to the present day, in fits and starts. Moreover, Syriac is still used in the liturgy of several Christian churches mostly in the Middle East, notably the Syrian Orthodox Church and the Syrian Catholic Church.

In scattered pockets in today’s Middle East, particularly in Iraq and Syria, Aramaic survives as a spoken language. These languages/dialects are known by a bewildering number of names, including “Neo-Syriac.” It is difficult to say, however, if any of them are direct continuations of classical Syriac, or of some similar Aramaic dialects.

The illustration featured here is the first page of a manuscript of The Book of Entertaining Stories, which was written about the year 1280 AD. The manuscript (dating to the 19th century) is now in Leeds, England, and is used here by permission. The author of the Book was one Gregory Bar-Hebraeus (1226-1286 AD). Bar-Hebraeus was born in a village called Ebra, in modern-day eastern Turkey. In the course of a long priestly career, he ended up as second-in-command of the Syrian Orthodox Church. He was a prolific writer: a recent bio-biography of his works in both manuscript and printed editions extends to over 500 pages. For this book, Bar-Hebraeus gathered edifying stories and anecdotes from many different cultures and languages, and turned them into Syriac. He wrote this work towards the end of his life, when he had intimations of his demise, “to wash away grief from the heart” as a “consolation to those who are sad.” As illustrated above, many of these stories are quite amusing, even today. Other anecdotes invoke wise men of ancient Persia, doctors, poor people, and more. There are a surprising number of stories involving “demoniacs,” that is, people possessed by demons; these are most probably stories involving the mentally ill. This work of his is probably the only work of Syriac literature known to non-specialists. It has been translated into many languages, including Czech, Ukrainian, and Malayalam. It was edited in 1897 by E.A. Wallis Budge: The Laughable Stories Collected by Mar Gregory John Bar-Hebraeus, on the basis of two manuscripts.

Syriac studies have traditionally flourished in Europe, less so in the United States. In the last thirty or so years, Syriac studies both here and abroad have undergone something of a Renaissance. In 1992, in New Jersey, an institution called The Syriac Institute in English and Beth Mardutho (“House of Learning”) in Syriac was founded, with the goal of “the establishment of a Syriac studies center affiliated with leading universities that globalizes Syriac studies through the Internet.” Some four years ago, after a long hiatus, Syriac was again taught at Cal, within the larger context of Aramaic studies.

Contribution by John L. Hayes,

Lecturer, Department of Near Eastern Studies

Sources consulted:

- Hidemi Takahashi. Barhebraeus: A Bio-Bibliography. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. 2005.

- E.A. Wallis Budge. The Laughable Stories Collected by Mar Gregory John Bar-Hebraeus. London: Luzac and Co. 1897.

Author: Gregory Bar-Hebraeus (1226-1286 AD), the Syriac text edited with an English translation by E. A. Wallis Budge.

Imprint: London: Luzac and co., 1897.

Language: Syriac

Language Family: Afro-Asiatic, Semitic, Northwest Semitic

Source: HathiTrust Digital Library (UC Berkeley)

URL: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t5z60pc3k