23 Resources over Time

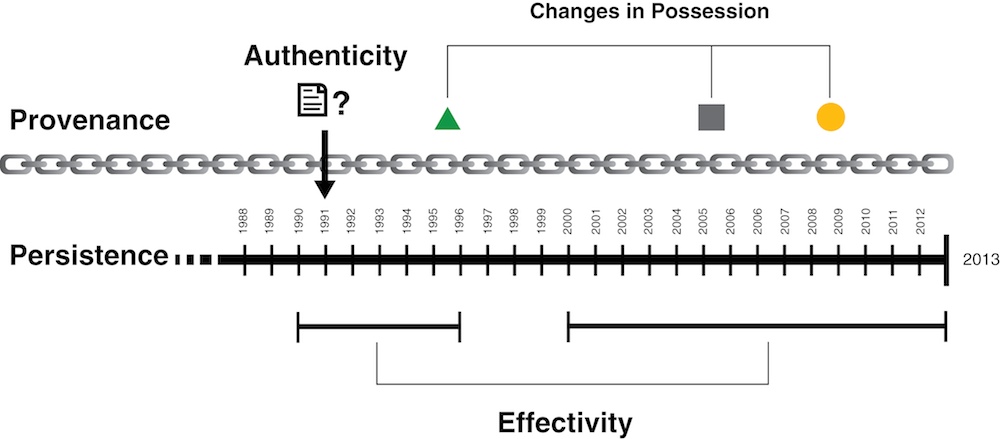

Problems of “what is the resource?” and “how do we identify it?” are complex and often require ongoing work to ensure they are properly answered as an organizing system evolves. We might need to know how a resource does or does not change over time (its persistence), whether its state and content come into play at a specified point in time (its effectivity), whether the resource is what it is said to be (its authenticity), and sometimes who has certified its authenticity over time (its provenance). A resource might have persistence, but only the provenance provided by an documented chain of custody enables questions about authenticity to be answered with authority. Effectivity describes the limits of a resource’s lifespan on the time line.

Four considerations that arise with respect to the maintenance of resources over time are their persistence, provenance, authenticity, and effectivity.

Figure: Resources over Time. portrays the relationships among the concepts of Persistence, Provenance, Effectivity, and Authenticity.

Persistence

Even if you have reached an agreement as to the meaning of “a thing” in your organizing system, you still face the question of the identity of the resource over time, or its persistence.

Persistent Identifiers

How long must an identifier last? Coyle gives the conventional, if unsatisfying, answer: “As long as it is needed.”[1] In some cases, the time frame is relatively short. When you order a specialty coffee and the barista asks for your name, this identifier only needs to last until you pick up your order at the end of the counter. But other time frames are much longer. For libraries and repositories of scientific, economic, census, or other data the time frame might be “forever.”

The design of a scheme for persistent identifiers must consider both the required time frame and the number of resources to be identified. When the Internet Protocol(IP) was designed in 1980, it contained a 32-bit address scheme, sufficient for over 4 billion unique addresses. But the enormous growth of the Internet and the application of IP addresses to resources of unexpected types have required a new addressing scheme with 128 bits.[2]

Recognition that URIs are often not persistent as identifiers for web-based resources led the Association of American Publishers(AAP) to develop the Digital Object Identifier(DOI) system. The location and owner of a digital resource can change, but its DOI is permanent.[3]

Persistent Resources

Even though persistence often has a technology dimension, it is more important to view it as a commitment by an institution or organization to perform activities over time to ensure that a resource is available when it is needed. Put another way, preservation (“Preservation”) and governance (“Governance”) are activities carried out to ensure the outcome of persistence.

The subtle relationship between preservation and persistence raises some interesting questions about what it means for a resource to stay the same over time. One way to think of persistence is that a persistent resource is never changed. However, physical resources often require maintenance, repair, or restoration to keep them accessible and usable, and we might question whether at some point these activities have transformed them into different resources.[4] Likewise, digital resources require regular backup and migration to keep them available and this might include changing their digital format.

Many resources like online newspapers or blog feeds continually change their content but still have persistent identifiers. This suggests we should think of persistence more abstractly, and consider as persistent resources any that remain functionally the same to support the same interactions at any point in their lifetimes, even if their physical properties or information values change.

Active resources implemented as computational agents or web services might be re-implemented numerous times, but as long as they do not change their interfaces they can be deemed to be persistent from the perspective of other resources that use them. Similarly, the dataset that defines a user or customer model in a recommendation system should be treated as a persistent resource; it includes information like name and date of birth that is persistent in the traditional sense; but it might also include “last purchase” and “current location,” which must change frequently to maintain the accuracy and usefulness of the customer model.

Some organizing systems closely monitor their resources and every interaction with them to prevent or detect tampering or other unauthorized changes. Some organizing systems, like those for software or legal documents, explicitly maintain every changed version to satisfy expectations of persistence, because different users might not be relying on the same version. With digital resources, determining whether two resources are the same or determining how they are related or derived from one another are very challenging problems.[5]

Effectivity

Many resources, or their properties, also have locative or temporal effectivity, meaning that they come into effect at a particular time and/or place; will almost certainly cease to be effective at some future date, and may cease to be effective in different places.

Temporal effectivity, sometimes known as “time-to-live,” is generally expressed as a range of two dates. It consists of a date on which the resource is effective, and optionally a date on which the resource ceases to be effective, or becomes stale. For some types of resources, the effective date is the moment they are created, but for others, the effective date can be a time different from the moment of creation. For example, a law passed in November may take effect on January 1 of the following year, and credit cards first need to be activated and then can no longer be used after their expiration date. An “effective date” is the counterpart of the “Best Before” date on perishable goods. That date indicates when a product goes bad, whereas an item’s effective date is when it “goes good” and the resource that it supersedes needs to be disposed of or archived.

Locative effectivity considers borders, security, roadways, altitude, depth and other geographic factors. Some types of resources, including people, are restricted as to where they may or may not be transported and/or used, such as hazardous cargo, explosives, narcotics, pharmaceuticals, alcohol, and cannabinoids. Jurisdictional issues concern borders, transportation corridors, weather stations, and geographic surveys. Parachutes are altitude-sensitive and scuba diving cylinders are depth-sensitive.

Effectivity concerns sometimes intersect with authority control for names and places. Name changes for resources often are tied to particular dates, events, and locations. Laws and regulations differ across organizational and geopolitical boundaries, and those boundaries often change. Some places that have been the site of civil unrest, foreign occupation, and other political disruptions have had many different names over time, and even at the same time.[6]

Today these disputed borders cause a problem for Google Maps when it displays certain international borders. Because Google is subject to the laws of the country where its servers are located, it must present disputed borders to conform with the point of view of the host country when a country-specific Google site is used to access the map.[7]

In most cases effectivity implies persistence requirements because it is important to be able to determine and reconstruct the configuration of resources that was in effect at some prior time. A new tax might go into effect on January 1, but if the government audits your tax returns what matters is whether you followed the law that was in effect when you filed your returns.[8]

Authenticity

In ordinary use we say that something is authentic if it can be shown to be, or has come to be accepted as what it claims to be. The importance and nuance of questions about authenticity can be seen in the many words we have to describe the relationship between “the real thing” (the “original”) and something else: copy, reproduction, replica, fake, phony, forgery, counterfeit, pretender, imposter, ringer, and so on.

It is easy to think of examples where authenticity of a resource matters: a signed legal contract, a work of art, a historical artifact, even a person’s signature.

The creator or operator of an organizing system, whether human or machine, can authenticate a newly created resource. A third party can also serve as proof of authenticity. Many professional careers are based on figuring out if a resource is authentic.[9]

There is a large body of techniques for establishing the identity of a person or physical resource. We often use judgments about the physical integrity of recorded information when we consider the integrity of its contents.

Digital authenticity is more difficult to establish. Digital resources can be reproduced at almost no cost, exist in multiple locations, carry different names on identical documents or identical names on different documents, and bring about other complications that do not arise with physical items. Technological solutions for ensuring digital authenticity include time stamps, watermarking, encryption, and digital signatures. However, while scholars generally trust technological methods, technologists are more skeptical of them because they can imagine ways for them to be circumvented or counterfeited. Even when a technologically sophisticated system for establishing authenticity is in place, we can still only assume the constancy of identity as far back as this system reaches in the “chain of custody” of the document.

Provenance

In “Looking “Upstream” and “Downstream” to Select Resources” we recommended that you analyze any evidence or records about the use of resources as they made their way to you from their headwaters to ensure they have maintained their quality over time. The concept of provenance transforms the passive question of “what has happened to this resource?” into actions that can be taken to ensure that nothing bad can happen to a resource or to enable it to be detected.

The idea that important documents must be created in a manner that can be authenticated and then preserved, with an unbroken chain of custody, goes back to ancient Rome. Notaries witnessed the creation of important documents, which were then protected to maintain their integrity or value as evidence. In organizing systems like museums and archives that preserve rare or culturally important objects or documents this concern is expressed as the principle of provenance. This is the history of the ownership of a collection or the resources in it, where they have been and who has had access to the resources.

A uniquely Chinese technique in organizing systems is the imprinting of elaborate red seals on documents, books, and paintings that collectively record the provenance of ownership and the review and approval of the artifact by emperors or important officials.

However, it is not only art historians and custodians of critical documents that need to be concerned with provenance. If you are planning to buy a used car, it is wise to check the vehicle history (using the Vehicle Identification Number, the car’s persistent identifier) to make sure it hasn’t been wrecked, flooded, or stolen.

-

IP v6 for Internet addresses. The threat of exhaustion was the motivation for remedial technologies, such as classful networks, Classless Inter-Domain Routing(CIDR) methods, and Network Address Translation(NAT) that extend the usable address space.

-

Digital Object Identifier(DOI) system (

http://www.doi.org). However, DOI has its issues too. It is a highly political, publisher-controlled system, not a universal solution to persistence. -

This is called the Paradox of Theseus, a philosophical debate since ancient times. Every day that Theseus’s ship is in the harbor, a single plank gets replaced, until after a few years the ship is completely rebuilt: not a single original plank remains. Is it still the ship of Theseus? And suppose, meanwhile, the shipbuilders have been building a new ship out of the replaced planks? Is that the ship of Theseus? (Furner 2008, p. 6).

-

See

http://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/hist_country_names.htmfor a list of formerly used country names and their respective effectivity. -

See (Gravois 2010). One specific example of this effect of international geopolitics on an organizing system involves the northern border of the Crimean Peninsula. When running a query for “Ukraine” via

google.com/maps(USA), the border appears as a dotted line, which reflects a “neutral” perspective in the aftermath of recent political and military conflicts. Alternatively, when submitting the same query viagoogle.com.ua/maps(Ukraine), there is no border at all, which is a reflection of a Ukrainian perspective that the Crimean Peninsula is part of Ukraine. Lastly, when the query is submitted viagoogle.ru/maps(Russia), the border is represented as a solid line, which reflects a Russian perspective that the territory is part of Russia. A 2014 study of Google Maps found 32 situations where the answer to “what country is that on the map?” depended on where it was asked (Yanovsky 2014) -

Effectivity in the tax code is simple compared to that relating to documents in complex systems, like commercial aircraft. Because of their long lifetimes—the Boeing 737 has been flying since the 1960s—and continual upgrading of parts like engines and computers, each airplane has its own operating and maintenance manual that reflects changes made to the plane over time. Every change to the plane requires an update to the repair manual, making the old version obsolete. And while an aircraft mechanic might refer to “the 737 maintenance manual,” each 737 aircraft actually has its own unique manual.

-

A notary public is used to verify that a signature on an important document, such as a mortgage or other contract, is authentic, much as signet rings and sealing wax once proved that no one has tampered with a document since it was sealed.