54 Faceted Classification

We have noted several times that strictly enumerative classifications constrain how resources are assigned to categories and how the classification can evolve over time. Faceted classifications are an alternative that overcome some of these limitations. In a faceted classification system, each resource is described using properties from multiple facets, but a person searching for resources does not need to consider all of the properties (and consequently the facets) and does not need to consider them in a fixed order, which an enumerative hierarchical classification requires.

Faceted classifications are especially useful in web user interfaces for online shopping or for browsing a large and heterogeneous museum collection. The process of considering facets in any order and ignoring those that are not relevant implies a dynamic organizational structure that makes selection both flexible and efficient. We can best illustrate these advantages with a shopping example in a domain that we are familiar with from “Multiple Properties”.

If a department store offers shirts in various styles, colors, sizes, brands, and prices, shoppers might want to search and sort through them using properties from these facets in any order. However, in a physical store, this is not possible because the shirts must be arranged in actual locations in the store, with dress shirts in one area, work shirts in another, and so on.

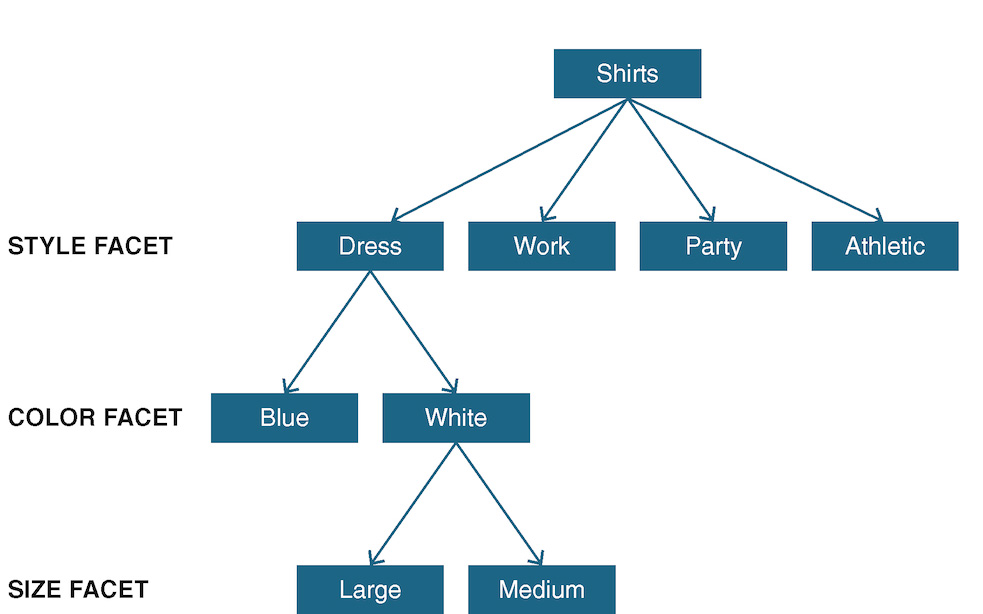

Assume that the shirt store has shirts in four styles: dress shirts, work shirts, party shirts, and athletic shirts. The dress shirts come in white and blue, the work shirts in white and brown, and the party and athletic shirts come in white, blue, brown, and red. White dress shirts come in large and medium sizes.

Suppose we are looking for a white dress shirt in a large size. We can think of this desired shirt in two equivalent ways, either as a member of a category of “large white dress shirts” or a shirt with “dress,” “white,” and “large” values on style, color, and size facets. Because of the way the shirts are arranged in the physical store, our search process has to follow a hierarchical structure of categories. We go to the dress shirt section, find white shirts, and then look for a large one. This process corresponds to the hierarchy shown in Figure: Enumerative Classification with Style Facet Followed by Color Facet.

In an enumerative classification system the order of the facets determines the classification hierarchy. For example, a store might classify shirts first using a style facet, next with a color facet, and finally with a size facet. This ordering could result in two piles of dress shirts, one blue and one white, in which each pile contains shirts of large and medium sizes.

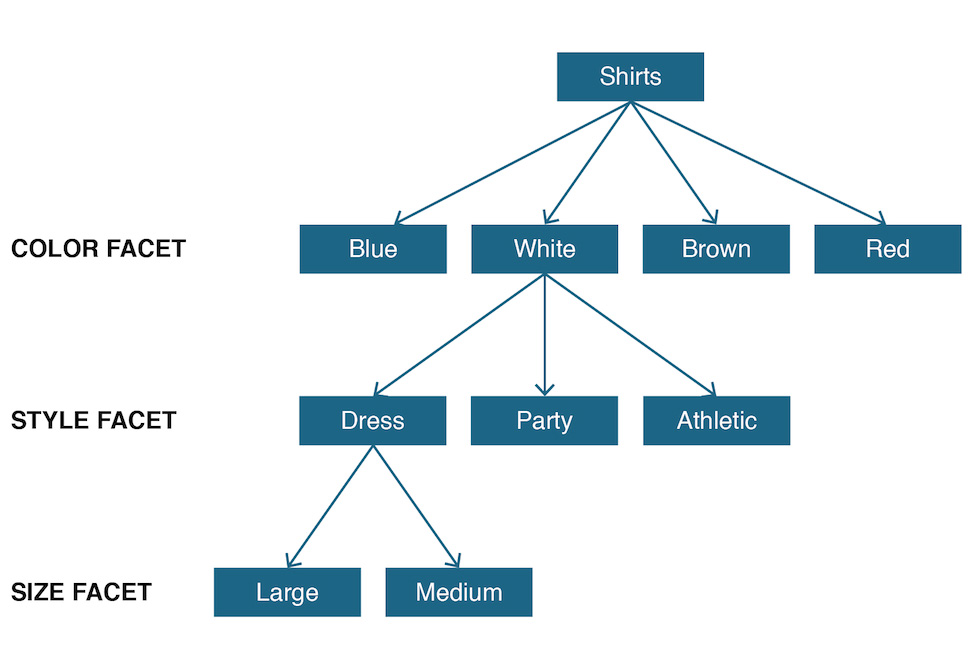

Although unlikely, a store might choose to organize its shirts by color. In our search for a “white dress shirt in a large size,” if we consider the color first, because shirts come in four colors, there are four color categories to choose from. When we choose the white shirts, there is no category for work shirts because there are no work shirts that come in white. We then choose the dress shirts, and then finally find the large one. (Figure: Enumerative Classification with Color Facet Followed by Style Facet.)

This department store example shows that for a physical organization, one property facet guides the localization of resources; all other facets are subordinated under the primary organizing property. In hierarchical enumerative classifications, this means that the primary organizing facet determines the primary form of access. The shirts are either organized by style and then color, or by color then style, which enforces an inflexible query strategy (style first or color first).

An alternative ordering of the same shirt facets changes the classification hierarchy. If the first facet considered is color, style is next, and finally size, this ordering could result in two piles of white shirts, one for dress shirts and one for athletic shirts, in which each pile contains shirts of large and medium sizes.

In an online store, however, descriptions of the shirts are being searched and sorted instead of the real shirts, and different organizations are possible. When the shirts are described using a faceted classification system, we treat all facets independently (i.e., they can all be the primary facet).

We can enumerate all the properties needed to assign resources appropriately, but we create the categories (i.e., union of properties from different facets) only as needed to sort resources with a particular combination of properties.

An additional aspect of the flexibility of faceted classification is that a facet can be left out of a resource description if it is not needed or appropriate. For example, because party shirts are often multi-colored with exotic patterns, it is not that useful to describe their color. Likewise, certain types of athletic shirts might be very loose-fitting, and as a result not be given a size description, but their color is important because it is tied to a particular team. Figure: Faceted Classification. shows how these two resource types can be classified with the faceted Shirt classification. Resource 1 describes a party shirt in medium; resource 2 describes an athletic shirt in blue without information about size.

In a pure faceted classification, not every facet needs to apply to every resource, and there is no requirement for a predetermined order in which the facets are considered.

A faceted classification scheme like that shown in Figure: Faceted Classification. eliminates the requirement for predetermining a combination and ordering of facets like those in Figure: Enumerative Classification with Style Facet Followed by Color Facet. and Figure: Enumerative Classification with Color Facet Followed by Style Facet. Instead, imagine a shirt store where you decide when you begin shopping which facets are important to you (“show me all the medium party shirts,” “show me the blue athletic shirts”) instead of having to adhere to whatever predetermined (pre-combined) enumerative classification the store invented. In a digital organizing system, faceted classification enables highly flexible access because prioritizing different facets can dynamically reorganize how the collection is presented.

Foundations for Faceted Classification

In library and information science texts it is common to credit the idea of faceted classification to S.R. Ranganathan, a Hindu mathematician working as a librarian. Ranganathan had an almost mystical motivation to classify everything in the universe with a single classification system and notation, considering it his dharma (the closest translation in English would be “fundamental duty” or “destiny”). Facing the limitations of Dewey’s system, where an item’s essence had to first be identified and then the item assigned to a category based on that essence, Ranganathan believed that all bibliographic resources could be organized around a more abstract variety of aspects.

In 1933 Ranganathan proposed that a set of five facets applied to all knowledge:

- Personality

-

The type of thing.

- Matter

-

The constituent material of the thing.

- Energy

-

The action or activity of the thing.

- Space

-

Where the thing occurs.

- Time

-

When the thing occurs.

This classification system is known as colon classification (or PMEST) because the notation used for resource identifiers uses a colon to separate the values on each facet. These values come from tables of categories and subcategories, making the call number very compact. Colon classification is most commonly used in libraries in India.[1]

For example, a book on “research in the cure of tuberculosis of lungs by x-ray conducted in India in 1950” has a Personality facet value of Medicine, a Matter facet value of Lungs with tuberculosis, an Energy facet value of Treatment using X-rays, a Space facet value of India, and a Time facet value of 1950. When the alphanumeric codes for these values are looked up in the classification tables, the composed call number is L,45;421:6;253:f.44’N5.[2]

Ranganathan deserves credit for implementing the first faceted classification system, but people other than librarians generally credit the idea to Nicolas de Condorcet, a French mathematician and philosopher. About 140 years before Ranganathan, Condorcet was concerned that “systems of classification that imposed a given interpretation upon Nature… represented an insufferable obstacle to… scientific advance.” Condorcet thus proposed a flexible classification scheme for “arranging a large number of subjects in a system so that we may straightway grasp their relations, quickly perceive their combinations, and readily form new combinations.”[3]

Condorcet’s system was based on five major facet categories, divided into 10 terms each, yielding 10^5 or 100,000 combinations:

- Objects

-

domains of study.

- Methods

-

for studying objects and describing the knowledge gained.

- Points of view

-

for studying objects.

- Uses and utility

-

of knowledge.

- Ways

-

in which knowledge can be acquired.[4]

Condorcet and Ranganathan proposed different facets, but both hoped that their five top-level facets would be sufficient for a universal classification system. People have generally rejected the idea of universal facets, but Ranganathan’s proposals continue to influence the development of the Library of Congress Subject Headings (LCSH).[5]

Faceted classification is most commonly used in narrow domains, each with its own specific facets. This makes intuitive sense because even if resources can be distinguished with a general classification, doing so requires lengthy notations, and it is much harder to add to a general classification than to a classification created specifically for a single subject area. We could probably describe shirts using the PMEST facets, but style, color, and size seem more natural.

Faceted Classification in Description

Elaine Svenonius defines facets as “groupings of terms obtained by the first division of a subject discipline into homogeneous or semantically cohesive categories.”[6] The relationships between these facets results in a controlled vocabulary (“Identity, Identifiers, and Names”) governing the resources we are organizing. From this controlled vocabulary we can generate many descriptions that are complex but formally structured, enabling us to describe things for which terms do not yet exist.

Getty’s Art & Architecture Thesaurus(AAT) is a robust and widely used controlled vocabulary consisting of generic terms to describe artifacts, objects, places and concepts in the domains of “art, architecture, and material culture.”[7]

AAT is a thesaurus with a faceted hierarchical structure. The AAT’s facets are “conceptually organized in a scheme that proceeds from abstract concepts to concrete, physical artifacts:”

- Associated Concepts

-

Concepts, philosophical and critical theory, and phenomena, such as “love” and “nihilism.”

- Physical Attributes

-

Material characteristics that can be measured and perceived, like “height” and “flexibility.”

- Styles and Periods

-

Artistic and architectural eras and stylistic groupings, such as “Renaissance” and “Dada.”

- Agents

-

Basically, people and the various groups and organizations with which they identify, whether based on physical, mental, socio-economic, or political characteristics—e.g., “stonemasons” or “socialists.”

- Activities

-

Actions, processes, and occurrences, such as “body painting” and “drawing.” These are different from the “Objects” facet, which may also contain “body painting,” in terms of the actual work itself, not the creation process.

- Materials

-

Concerned with the actual substance of which a work is made, like “metal” or “bleach.” “Materials” differ from “Physical Attributes” in that the latter is more abstract than the former.

- Objects

-

The largest facet, objects contains the actual works, like “sandcastles” and “screen prints.”

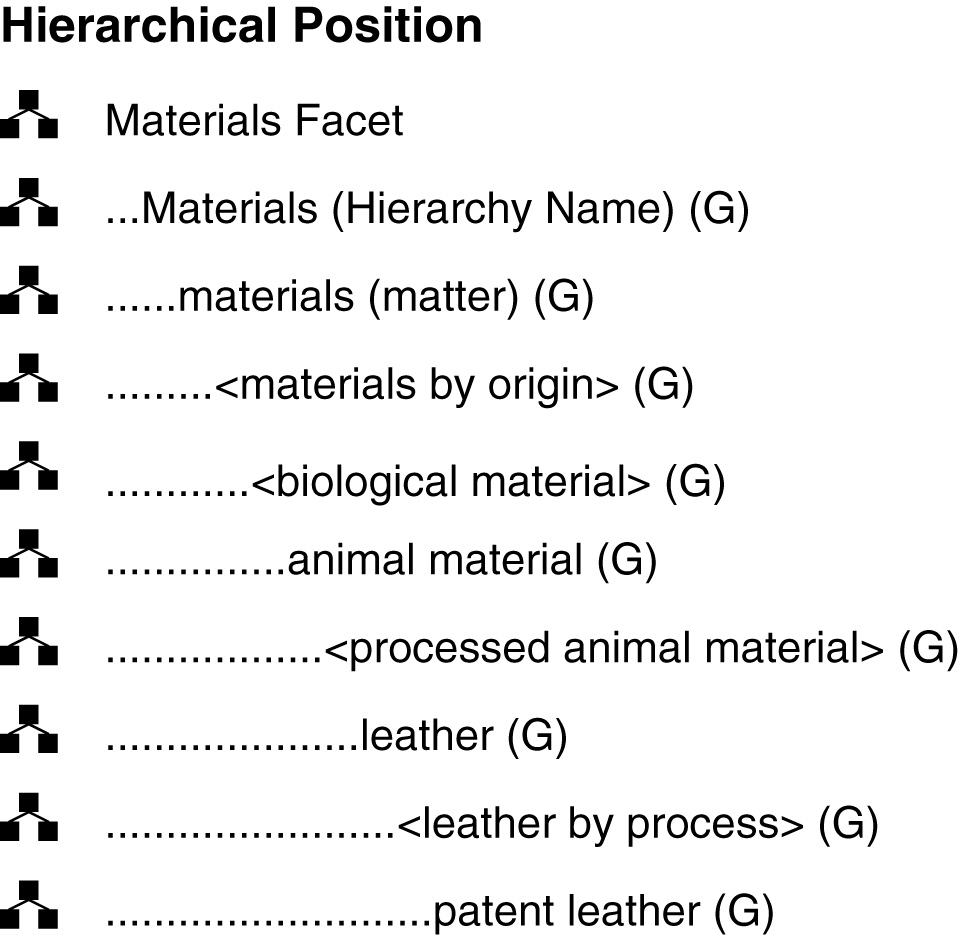

Within each facet is a strict hierarchical structure drilling down from broad term to very specific instance.

The Art and Architecture Thesaurus has a faceted hierarchical structure. For example, the materials facet distinguishes the material of “patent leather” according to the process applied to processed animal material, which is a type of biological material, and so on.

Figure: “Patent Leather” in the Art & Architecture Thesaurus. shows how a particular instance may be described on a number of dimensions for the purpose of organizing the item and retrieving information about it. And by using a standard controlled vocabulary, catalogers and indexers make it easier for users to understand and adapt to the way things are organized for the purpose of finding them.[8]

A Classification for Facets

There are four major types of facets.

- Enumerative facets

-

Have mutually exclusive possible values. In our online shirt store, “Style” is an enumerative facet whose values are “dress,” “work,” “party,” and “athletic.”

- Boolean facets

-

Take on one of two values, yes (true) or no (false) along some dimension or property. On a sportswear website, “Waterproof” would be a Boolean facet because an item of clothing is either waterproof or it is not.

- Hierarchical facets

-

Organize resources by logical inclusion (“Inclusion”). At Williams-Sonoma’s website, the top-level facet includes “Cookware,” “Cooks’ Tools,” and “Cutlery.” At wine.com the “Region” facet has values for “US,” “Old World,” and “New World,” each of which is further divided geographically. [9] Also see taxonomic facets.

- Spectrum facets

-

Assume a range of numerical values with a defined minimum and maximum. Price and date are common spectrum facets. The ranges are often modeled as mutually exclusive regions (potential price facet values might include “$0—$49,” “$50—$99,” and “$100—$149”).

Designing a Faceted Classification System

It is important to be systematic and principled when designing a faceted classification. In some respects the process and design concerns overlap with those for describing resources, and much of the advice in “The Process of Describing Resources” is relevant here.[10]

Design Process for Faceted Classification

We advocate a five step process for designing a faceted classification system.

-

Define the purposes of the classification (“Determining the Purposes”, “Classification Is Purposeful”) and specify the collection of concepts or resources to be classified.

-

For each facet, determine its logical type (“A Classification for Facets”) and possible values. Specify the order of the values for each facet so that they make sense to users; useful orderings are alphabetical, chronological, procedural, size, most popular to least popular, simple to complex, and geographical or topological.

-

Analyze and describe a representative sample of resource instances to identify properties or dimensions as candidate facets (See “Identifying Properties”).

-

Examine the relationships between the facets to create sub-facets if necessary. Determine how the facets will be combined to generate the classifications.

-

Test the classification on new instances, and revise the facets, facet values, and facet grammar as needed.

Design Principles and Pragmatics

Here is some more specific advice about selecting and designing facets and facet values:

- Orthogonality

-

Facets should be independent dimensions, so a resource can have values of all of them while only having one value on each of them. In an online kitchen store, one facet might be “Product” and another might be “Brand.” A particular item might be classified as a “Saucepan” in the “Product” facet and as “Calphalon” in the “Brand” one. Other saucepans might have other brands, and other Calphalon products might not be saucepans, because Product and Brand are orthogonal.

- Semantic Balance

-

Top-level facets should be the properties that best differentiate the resources in the classification domain. The values should be of equal semantic scope so that resources are distributed among the subcategories. Subfacets of “Cookware” like “Sauciers and Saucepans” and “Roasters and Brasiers” are semantically balanced as they are both named and grouped by cooking activity.[11]

- Coverage

-

The values of a facet should be able of classifying all instances within the intended scope.

- Scalability

-

Facet values must accommodate potential additions to the set of instances. Including an “Other” value is an easy way to ensure that a facet is flexible and hospitable to new instances, but it not desirable if all new instances will be assigned that value.

- Objectivity

-

Although every classification has an explicit or implicit bias (“Classification Is Biased”), facets and facet values should be as unambiguous and concrete as possible to enable reliable classification of instances.

- Normativity

-

To make a faceted classification as useful by as many people as possible, the terms used for facets and facet values should not be idiosyncratic, metaphorical, or require special knowledge to interpret.[12]

As we will see in “Computational Classification”, classification can sometimes be done by computers rather than by people. Computer algorithms can analyze resource properties and descriptions to identify dimensions on which resources differ and the most frequent descriptive terms, which can then be used to design a faceted classification scheme. Resources can then be assigned to the appropriate categories, either without human intervention or in collaboration with a human who trains the algorithm with classified instances.

-

(Ranganathan 1967). (Satija 2001). See (Svenonius 2000, p. 174-176) for a quick introduction.

-

Wikipedia article at

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colon_classification. -

(Baker 1962). The first quote is on page 104; the second one is on page 100. This article contains Condorcet’s 1805 essay in French, but fortunately for us Baker’s analysis is in English, This motivation of Condorcet’s classification scheme sounds like the description of a data warehouse or business intelligence system in which transactional data can be “sliced and diced” into new combinations to answer questions in support of strategic decision-making. See (Watson and Wixon 2007).

-

See Joacim Hansson, Condorcet and the Origins of Faceted Classification,

http://documentationandlibrarianship.blogspot.com/2011/02/condorcet-and-origins-of-faceted.html. -

LCSH uses facets for Topic, Place, Time, and Form (but they can be ordered in a variety of ways, not as rigidly as PMEST. (Anderson and Hoffman 2006) argue for a fully faceted syntax in LCSH.

-

The Getty AAT is online at

http://www.getty.edu/research/tools/vocabularies/aat/index.html. -

This section of the thesaurus comes from

http://www.getty.edu/vow/AATFullDisplay?find=leather8logic=AND8note=8english=N8prev_page=18subjectid=300193362. -

You might have thought that the US was in the new world, but according to wine.com, the new world of wine includes Australia, New Zealand, Argentina, Chile, and South Africa. The geography under the US facet is equally distorted by the uneven distribution of quality wine making regions, so the values of that facet are California. Oregon, Washington, and Other US.

-

Denton, William. How to Make a Faceted Classification and Put It On the Web Nov. 2003.

http://www.miskatonic.org/library/facet-web-howto.html. See also (Spiteri 1998). -

Should remind you of issues of lexical gap in “The Lexical Perspective”.

-

Semantic balance is a bit hard to define, but you can often tell when facet values are not balanced. A cookware facet whose values include saucepans, frying pans, stock pots, and pizza pans will not evenly distribute resources across the facets.