22 Naming Resources

Determining the identity of the thing, document, information component, or data item we need is not always enough. We often need to give that resource a name, a label that will help us understand and talk about what it is. But naming is not just the simple task of assigning a sequence of characters. In this section, we will discuss why we name, some of the problems with naming, and the principles that help us name things in useful ways.

What’s in a Name?

When a child is born, its parents give it a name, often a very stressful and contentious decision. Names serve to distinguish one person from another, although names might not be unique—there are thousands of people named James Smith and Maria Garcia. Names also, intentionally or unintentionally, suggest characteristics or aspirations. The name given to us at birth is just one of the names we will be identified with during our lifetimes. We have nicknames, names we use professionally, names we use with friends, and names we use online. Our banks, our schools, and our governments will know who we are because of numbers they associate with our names. As long as it serves its purpose to identify you, your name could be anything.[1]

Resources other than people need names so we can find them, describe them, reuse them, refer or link to them, record who owns them, and otherwise interact with them. In many domains the names assigned to resources are also influenced or constrained by rules, industry practice, or technology considerations.

The Problems of Naming

Giving names to anything, from a business to a concept to an action, can be a difficult process and it is possible to do it well or do it poorly. The following section details some of the major challenges in assigning a name to a resource.

The Vocabulary Problem

Every natural language offers more than one way to express any thought, and in particular there are usually many words that can be used to refer to the same thing or concept. The words people choose to name or describe things are embodied in their experiences and context, so people will often disagree in the words they use. Moreover, people are often a bit surprised when it happens, because what seems like the natural or obvious name to one person is not natural or obvious to another. One way to avoid surprises is to have people cooperate in choosing names for resources, and information architects often use participatory design techniques of card sorting or free listing for this purpose.[2][3]

Back in the 1980s in the early days of computer user interface design, George Furnas and his colleagues at Bell Labs conducted a set of experiments to measure how much people would agree when they named some resource or function. The short answer: very little. Left to our own devices, we come up with a shockingly large number of names for a single common thing.

In one experiment, a thousand pairs of people were asked to “write the name you would give to a program that tells about interesting activities occurring in some major metropolitan area.” Less than 12 pairs of people agreed on a name. Furnas called this phenomenon the vocabulary problem, concluding that no single word could ever be considered the “best” name.[4]

Homonymy, Polysemy, and False Cognates

Sometimes the same word can refer to different resources—a “bank” can be a financial institution or the side of a river. When two words are spelled the same but have different meanings they are homographs; if they are also pronounced the same they are homonyms. If the different meanings of the homographs are related, they are polysemes.

Resources with homonymous and polysemous names are sometimes incorrectly identified, especially by an automated process that cannot use common sense or context to determine the correct referent. Polysemy can cause more trouble than simple homography because the overlapping meaning might obscure the misinterpretation. If one person thinks of a “shipping container” as being a cardboard box and orders some of them, while another person thinks of a “shipping container” as the large box carried by semi-trailers and stacked on cargo ships, their disagreement might not be discovered until the wrong kinds of containers arrive.[5]

Many words in different languages have common roots, and as a result are often spelled the same or nearly the same. This is especially true for technology words; for example, “computer” has been borrowed by many languages. The existence of these cognates and borrowed words makes us vulnerable to false cognates. When a word in one language has a different meaning and refers to different resources in another, the results can be embarrassing or disastrous. “Gift” is poison in German; “pain” is bread in French.

Names with Undesirable Associations

False cognates are a special category of words that make poor names, and there are many stories relating product marketing mistakes, where a product name or description translates poorly, into other languages or cultures, with undesirable associations.[6] Furthermore, these undesirable associations differ across cultures. For example, even though floor numbers have the straightforward purpose to identify floors from lowest to highest levels, most buildings in Western cultures skip the 13th floor because many people think 13 is an unlucky number. In many East and Southeast Asian buildings, the 4th floor is skipped. In China the number 4 is dreaded because it sounds like the word for “death,” while 8 is prized because it sounds like the word for “wealth.”

While it can be tempting to dismiss unfamiliar biases and beliefs about names and identifiers as harmless superstitions and practices, their implications are ubiquitous and far from benign. Alphabetical ordering might seem like a fair and non-discriminatory arrangement of resources, but because it is easy to choose the name at the top of an alphabetical list, many firms in service businesses select names that begin with “A,” “AA,” or even “AAA” (look in any printed service directory). A consequence of this bias is that people or resources with names that begin with letters late in the alphabet are systematically discriminated against because they are often not considered, or because they are evaluated in the context created by resources earlier in the alphabet rather than on their own merit.[7]

Names that Assume Impermanent Attributes

Many resources are given names based on attributes that can be problematic later if the attribute changes in value or interpretation.

Web resources are often referred to using URLs that contain the domain name of the server on which the resource is located, followed by the directory path and file name on the computer running the server. This treats the current location of the resource as its name, so the name will change if the resource is moved. It also means that resources that are identical in content, like those at an archive or mirror website, will have different names than the original even though they are exact copies. An analogous problem is faced by restaurants or businesses with street names or numbers in their names if they lose their leases or want to expand.[8]

Some dynamic web resources that are generated by programs have URIs that contain information about the server technology used to create them. When the technology changes, the URIs will no longer work.[9]

Some resources have names that include page numbers, which disappear or change when the resource is accessed in a digital form. For example, the standard citation format for legal opinions uses the page number from the printed volume issued by West Publishing, which has a virtual monopoly on the publishing of court opinions and other types of legal documents.[10]

Some resources have names that contain dates, years or other time indicators, most often to point to the future. The film studio named “20th Century Fox” took on that name in the 1930s to give it a progressive, forward-looking identity, but today a name with “20th Century” in it does the opposite.[11]

The Semantic Gap

The semantic gap is the difference in perspective in naming and description when resources are described by automated processes rather than by people.[12]

The semantic gap is largest when computer programs or sensors obtain and name some information in a format optimized for efficient capture, storage, decoding, or other technical criteria. The names—like IMG20268.jpg on a digital photo—might make sense for the camera as it stores consecutively taken photos but they are not good names for people. We may prefer names that describe the content of the picture, like GoldenGateBridge.jpg.

When we try to examine the content of computer-created or sensor-captured resources, like a clip of music or a compiled software program, a text rendering of the content simply looks like nonsense. It was designed to be interpreted by a computer program, not by a person.

Choosing Good Names and Identifiers

If someone tells you they are having dinner with their best friend, a cousin, someone with whom they play basketball, and their professional mentor from work, how many places at the table will be set? Anywhere from two to five; it is possible all those relational descriptions refer to a single person, or to four different people, and because “friend,” “cousin,” “basketball teammate” and “mentor” do not name specific people you will have to guess who is coming to dinner.

If instead of descriptions you are told that the dinner guests are Bob, Carol, Ted, and Alice, you can count four names and you know how many people are having dinner. But you still cannot be sure exactly which four people are involved because there are many people with those names.

The uncertainty is eliminated if we use identifiers rather than names. Identifiers are names that refer unambiguously to a specific person, place, or resource because they are assigned in a controlled way. Identifiers are often strings of numbers or letters rather than words to avoid the biases and associations that words can convey. For example, a professor might grade exams that are identified by student numbers rather than names.

The distinction between names and identifiers for people is often not appreciated. (See the sidebar, Names {and, or, vs} Identifiers.)

Make Names Informative

The most basic principle of naming is to choose names that are informative, which makes them easier to understand and remember. It is easier to tell what a computer program or XML document is doing if it uses names like “ItemCost” and “TotalCost” rather than just “I” or “T.” People will enter more consistent and reusable address information if a form asks explicitly for “Street,” “City,” and “PostalCode” instead of “Line1” and “Line2.”

Identifiers can be designed with internal structure and semantics that conveys information beyond the basic aspect of pointing to a specific resource. An International Standard Book Number(ISBN) like “978-0-262-07261-8” identifies a resource (07261=“Document Engineering”) and also reveals that the resource is a book (978), in English (0), and published by The MIT Press (262).[14]

The navigation points that mark intersections of radial signals from ground beacons or satellites that are crucial to aircraft pilots used to be meaningless five-letter codes that were changed to make them suggest their locations; semantic landmark names made pilots less likely to enter the wrong names into navigation systems, For example, some of the navigation points near Orlando, Florida—the home of Disney World—are MICKI, MINEE, and GOOFY.[15]

Use Controlled Vocabularies

One way to encourage good names for a given resource domain or task is to establish a controlled vocabulary. A controlled vocabulary is like a fixed or closed dictionary that includes the terms that can be used in a particular domain. A controlled vocabulary shrinks the number of words used, reducing synonymy and homonymy, eliminating undesirable associations, leaving behind a set of words with precisely defined meanings and rules governing their use.

A controlled vocabulary is not simply a set of allowed words; it also includes their definitions and often specifies rules by which the vocabulary terms can be used and combined. Different domains can create specific controlled vocabularies for their own purposes, but the important thing is that the vocabulary be used consistently throughout that domain.[16]

When evaluating what name to use for an author, librarians typically look for the name form that is used most commonly across that author’s body of work while conforming to rules for handling prefixes, suffixes and other name parts that often cause name variations. For example, a name like that of Johann Wolfgang von Goëthe might be alphabetized as both a “G” name and a “V” name, but using “G” is the authoritative way. “See” and “see also” references then map the variations to the authoritative name.[17]

Official authority files are maintained for many resource domains: a gazetteer associates names and locations and tells us whether we should be referring to Bombay or Mumbai; the Domain Name System(DNS) maps human-oriented domain and host names to their IP addresses; the Chemical Abstracts Service Registry assigns unique identifiers to every chemical described in the open scientific literature; numerous institutions assign unique identifiers to different categories of animal species.[18]

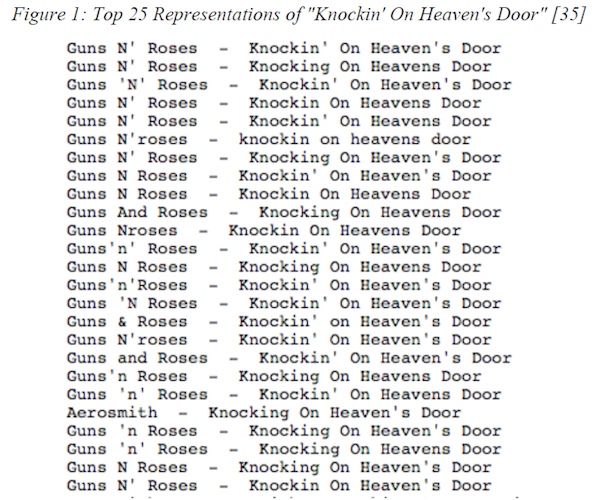

In some cases, authority files are created or maintained by a community, as in the case of MusicBrainz, an “open music encyclopedia” to which users contribute information about artists, releases, tracks, and other aspects of music. Music metadata is notoriously unreliable; one study found over 100 variations in the description of the Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door song (written by Bob Dylan) as recorded by Guns N’ Roses.[19]

Allow Aliasing

A controlled vocabulary is extremely useful to people who use it, but if you are designing an organizing system for other people who do not or cannot use it, you need to accommodate the variety of words they will actually use when they seek or describe resources. The authoritative name of a certain fish species is Amphiprion ocellaris, but most people would search for it as “clownfish,” “anemone fish,” or even by its more familiar film name of Nemo.

Furnas suggests “unlimited aliasing” to connect the uncontrolled or natural vocabularies that people use with the controlled one employed by the organizing system. By this he means that there must be many alternate access routes to each word or function that a user is trying to find. For example, the birth name of the 42nd President of the United States of America is “William Jefferson Clinton,” but web pages that refer to him as “Bill Clinton” are vastly more common, and searches for the former are redirected to the latter. A related mechanism used by search engines is spelling correction, essentially treating all the incorrect spellings as aliases of the correct one (“did you mean California?” when you typed “Claifornia”).

Make Identifiers Unique or Qualified

Even though an identifier refers to a single resource, this does not mean that no two identifiers are identical. One military inventory system might use stock number 99 000 1111 to identify a 24-hour, cold-climate ration pack, while another inventory system could use the same number to identify an electronic radio valve. Each identifier is unique in its inventory system, but if a supply request gets sent to the wrong warehouse hungry soldiers could be sent radio valves instead of rations.[20][21]

We can prevent or reduce identifier collisions by adding information about the namespace, the domain from which the names or identifiers are selected, thus creating what are often called qualified names. There are several dozen US cities named “Springfield” and “Washington,” but adding state codes to mail addresses distinguishes them. Likewise, we can add prefixes to XML element names when we create documents that reuse components from multiple document types, distinguishing <book:Title> from <legal:Title>.

We can fix problems like these by qualifying or extending the identifier, or by creating a globally unique identifier(GUID), one that will never be the same as another identifier in any organizing system anywhere else. One easy method to create a GUID is to use a URL you control and append a string to it, the same approach that gives every web page a unique address. GUIDs are often used to identify software objects, the resources in distributed systems, or data collections.[22]

Because they are not created by an algorithm whose results are provably unique, we do not consider fingerprints, or other biometric information, to be globally unique identifiers for people, but for all practical purposes they are.[23]

Distinguish Identifying and Resolving

Library call numbers are identifiers that do not contain any information about where the resource can be found in the library stacks on in a digital repository. This separation enables this identification system to work when there are multiple copies in different locations, in contrast to URIs that serve as both identifiers and locations much of the time. When the identifier does not contain information about resource location, it must be“resolved” to determine the location. With physical resources, resolution takes place with the aid of signs, maps, or other associated resources that describe the resource arrangement in some physical environment; for example, “You are here” maps associate each resource identifier with a coordinate or other means of finding it on the map. With digital resources, the resolver is a directory system or service that interprets an identifier and looks up its location or directly initiates resource retrieval.

-

Well, maybe not anything. Books list traditional meanings of various names, charts rank names by popularity in different eras, and dozens of websites tout themselves as the place to find a special and unique name. See

http://www.ssa.gov/oact/babynames/for historical trends about baby names in the US with an interactive visualization athttp://www.babynamewizard.com/voyager#.Different countries have rules about characters or words that may be used in names. In Germany, for example, the government regulates the names parents can give to their children; there’s even a book, the International Handbook of Forenames, to guide them (Kulish 2009). In Portugal, the Ministry of Justice publishes lists of prohibited names (BBC News, 2007a). Meanwhile, in 2007, Swedish tax officials rejected a family’s attempt to name their daughter Metallica (

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/6525475.stm).We can also change our names. Whether a woman takes on her husband’s surname after marriage or, like the California man who changed his name to “Trout Fishing,” we just find something that better suits us than our given name.

-

While you may think that certain terms are more obviously “good” than others, studies show that “there is no one good access term for most objects. The idea of an ‘obvious,’ ‘self-evident,’ or ‘natural’ term is a myth!” (Furnas et al. 1987, p. 967).

-

(Spencer 2009). Free listing (see

http://boxesandarrows.com/beyond-cardsorting-free-listing-methods-to-explore-user-categorizations/) -

The most common names for this service were activities, calendar and events, but in all over a hundred different names were suggested, including cityevents, whatup, sparetime, funtime, weekender, and nightout, “People use a surprisingly great variety of words to refer to the same thing,” Furnas wrote, “If everyone always agreed on what to call things, the user’s word would be the designer’s word would be the system’s word. ... Unfortunately, people often disagree on the words they use for things” (Furnas et al. 1987, p. 964).

-

This example comes from (Farish 2002), who analyzes “What’s in a Name?” and suggests that multiple names for the same thing might be a good idea because non-technical business users, data analysts, and system implementers need to see things differently and no one standard for assigning names will work for all three audiences.

-

See, for example, Handbook of Cross-Cultural Marketing, (Kaynak 1997).

-

See As easy as YZX,

http://www.economist.com/node/760345. In addition, the convention to list the co-authors of scientific publications in alphabetic order has been shown to affect reputation and employment by giving undeserved advantages to people whose names start with letters that come early in the alphabet. This bias might also affect admission to selective schools. (Efthyvoulou 2008). -

The Kentucky Fried Chicken franchise solved this problem by changing its name to KFC, which you can now find in Beijing, Moscow, London and other locations not anywhere near Kentucky and where many people have probably never heard of the place.

Why is the professional basketball team in Los Angeles called the “Lakers” when there are few natural lakes there? The team was originally located in Minneapolis, Minnesota, a state nicknamed “The Land of 10,000 Lakes.”

-

Tim Berners-Lee, the founder of the web, famously argued that Cool URIs Don’t Change (Berners-Lee 1998).

-

Any online citation to one of the West printed court reports will use the West format. However, when Mead Data wanted to use the West page numbers in its LEXIS online service to link to specific pages, West sued for copyright infringement. The citation for the West Publishing vs. Mead Data Central case is 799 F.2d 1219 (8th Cir 1986), which means that the case begins on page 1219 of volume 799 in the set of opinions from the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals that West published in print form. West won the case and Mead Data had to pay substantial royalties. Fortunately, this logic behind this decision was repudiated by the US Supreme Court a few years later in a case that West published as Feist Publications, Inc., v. Rural Telephone Service Co., 499 U.S. 340 (1991), and West can no longer claim copyright on page numbers.

-

When George Orwell gave the title “1984” to a novel he wrote in 1949, he intended it as a warning about a totalitarian future as the Cold War took hold in a divided Europe, but today 1984 is decades in the past and the title does not have the same impact.

-

Most common US surnames;

http://names.mongabay.com/most_common_surnames.htm.Chad Ochocinco story:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chad_Ochocinco.Fake names at Starbucks:

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424053111904106704576582834147448392.html.Twitter on sports jerseys:

http://www.forbes.com/sites/alexknapp/2011/12/30/pro-lacrosse-team-replaces-names-with-twitter-handles-on-jerseys/?partner=technology_newsletter. -

Identifiers with meaningful internal structure are said to be structured or intelligent. Those that contain no additional information are sometimes said to be unstructured, opaque, or dumb. The 8 in the ISBN example is a check digit, not technically part of the identifier, that is algorithmically derived from the other digits to detect errors in entering the ISBN.

-

(Svenonius 2000) calls vocabulary control “the sine qua non of information organization” (p. 89). “The imposition of vocabulary control creates an artificial language out of a natural language” (p. 89), leaving behind an official, normalized set of terms and their uses.

-

This mapping is “the means by which the language of the user and that of a retrieval system are brought into sync” (Svenonius 2000, p. 93) and allows an information-seeker to understand the relationship between, say, Samuel Clemens and Mark Twain. The Library of Congress(LOC) maintains a list of standard, accepted names for authors, subjects, and titles called the Name Authority File.

http://id.loc.gov/authorities/names.html. -

Pan-European Species Directory Infrastructure (PESI):

http://www.eu-nomen.eu/pesi; Consortium for the Barcode of Life (CBOL):http://www.barcoding.si.edu/; NatureServe:http://services.natureserve.org/BrowseServices/getSpeciesData/getSpeciesListREST.jsp. -

This rations / radio confusion is described in (Wheatley 2004). In 2008 a similar mistake in managing inventory at a US military warehouse led to missile launch fuses being sent to Taiwan instead of helicopter batteries, causing a high-level diplomatic furor when the Chinese government objected to this as a treaty violation (Hoffman 2008).

-

Organizing systems in libraries, museums, and businesses often give sequential accession numbers to resources when they are added to a collection, but these identifiers are of no use outside of the context in which they are assigned, as when a union catalog or merged database is created.

-

A more general technique is to use the Universally Unique Identifier(UUID) standard, which standardizes some algorithms that generate 128-bit tokens that, for all practical purposes, will be unique for hundreds, if not thousands, of years.

-

(OASIS 2003). The Organization for the Advancement of Structured Information Systems(OASIS) XML Common Biometric Format(XCBF) was developed to standardize the use of biometric data like DNA, fingerprints, iris scans, and hand geometry to verify identity (

https://www.oasis-open.org/committees/tc_home.php?wg_abbrev=xcbf).